From the Vault of Art Shay: "Hot Air" - Japan 1945

By Staff in News on Mar 16, 2011 4:00PM

The face of Japan in mid-August 1945 after five years of war is exactly what it is five days after the new earthquake and tsunami.

I circled our plane over Hiroshima at the height of the Hancock Building without a notion of the horror of radioactivity. The wreckage nears the rivers at Ground Zero, today parenthesize plants that make the Mazda and made my Lexus 56 years later.

Two European combat tours - 52 missions - behind me, I signed up for a peacetime tour of navigating the wounded home from Australia, New Guinea, Hawaii, Guam and Tokyo. I did not yet have the heart to photograph\r\na planeload of double amputees swathed in plaster, smiling at my Leica, jealous of my fingers and legs.

Coming into Atsugi Airport near Tokyo carrying 56 members of MacArthur\'s Occupation team.

Wars wind down. We had to wait days for GI maintenance crews to service our Air Transport Command monsters.

Three members of our crew started hiking through the mud to Yokohama and Tokyo, hoping to hitch a jeep ride. The bag contained Lucky Strikes, Baby Ruth bars and $500 in cash for purposes of trade.

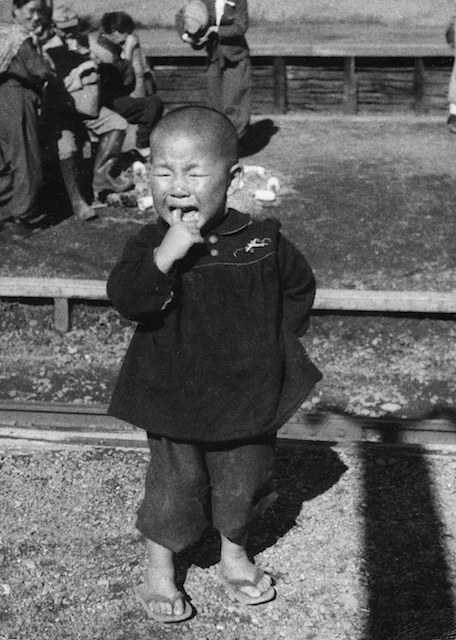

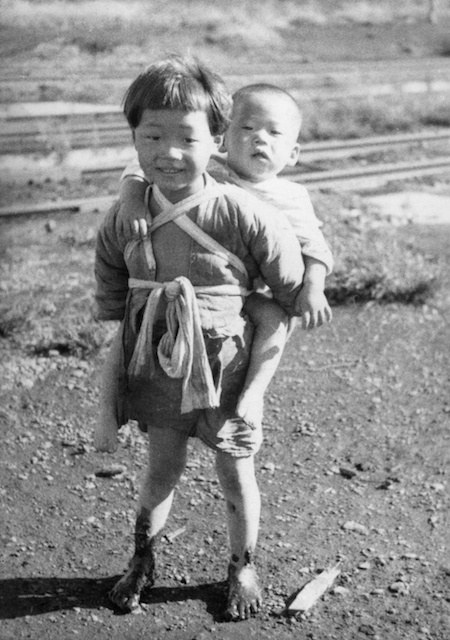

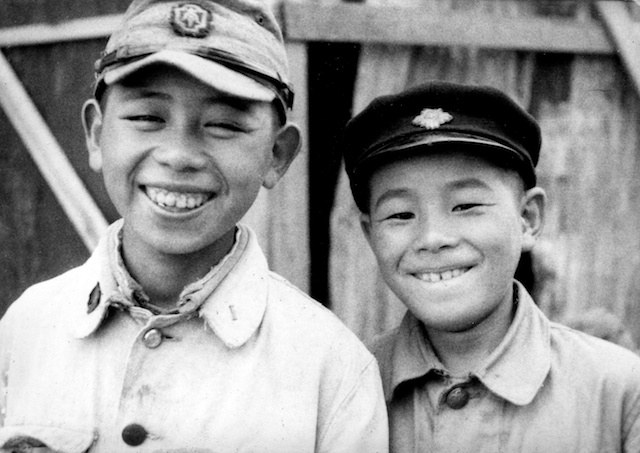

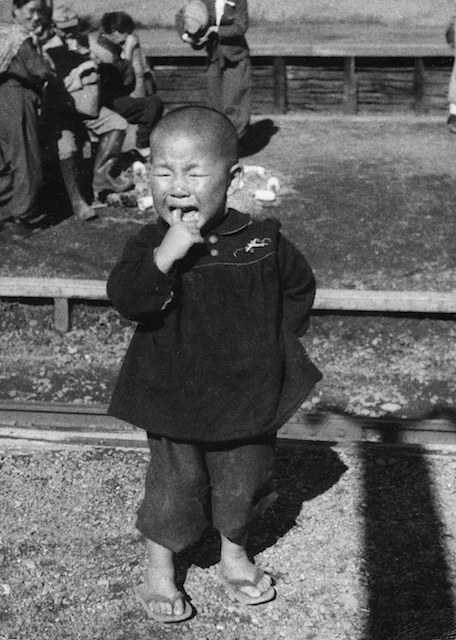

Kids appeared whenever and wherever we did.

I think our troops took possession of the unbombed building behind all the rubble.

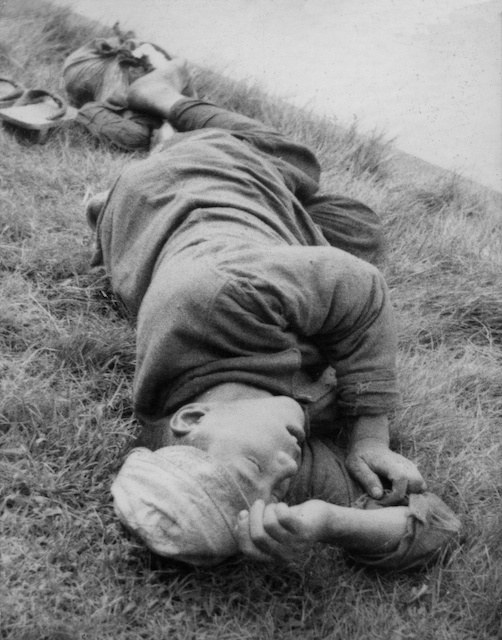

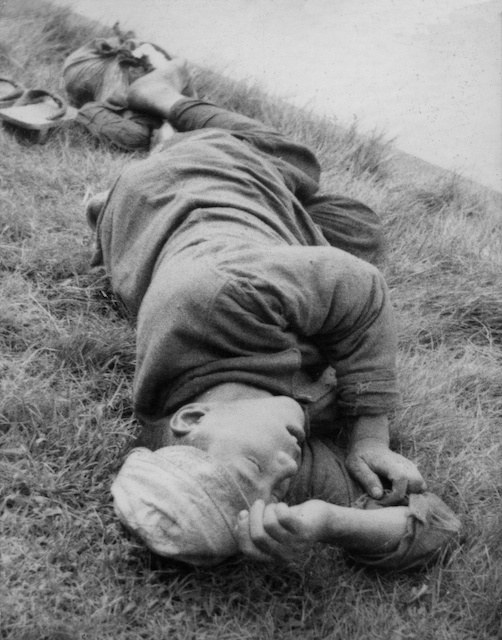

Dead or weary? We rarely made the effort to check. What would we do with the information.

On one of downtown Tokyo\'s dangerous main arteries an untended waif sits - a serene image related to the famous one made years earlier during Japan\'s conquest of Manchuria. A picture in which another homeless waif bawls his head off. We moved the kid to safety and filled his tiny pockets with yen.

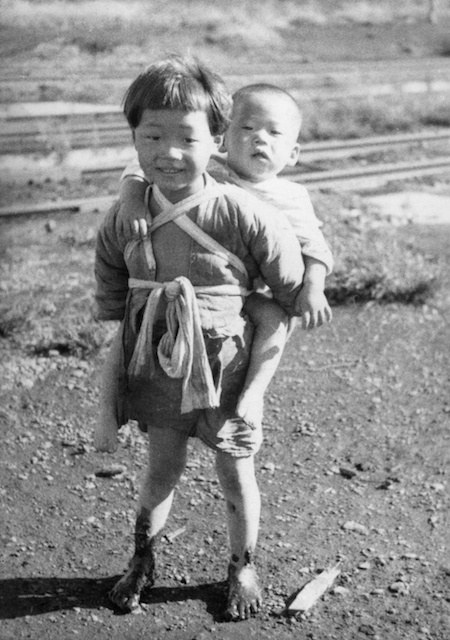

The muddy feet of this week\'s Tsunami survivors figuratively spring from \r\nthose of this loving 5-year-old, now 71 (unless radiation got her sooner ), carrying her kid brother to food and warmth. Their parents had been killed by an American firebomb that also destroyed her 200-year-old house. She accepted our yen with a smile and polite bow.

At a small suburban bank my copilot draws from his store of 50-cent Luckies and 5-cent Baby Ruth bars bought at the Guam PX, to trade up to a sexy $40 kimono belonging to the banker\'s wife.

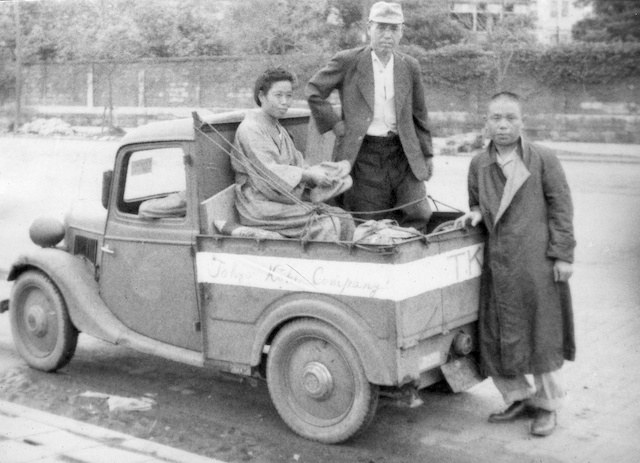

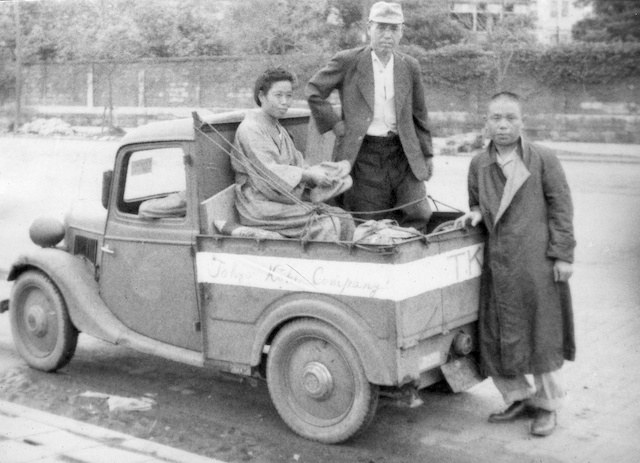

Isuzu and others made marvelous trucks like this one that helped farmers move to greener fields than the ones A-bombed.

A tough GI kept us from crossing the moat into the Imperial Palace.

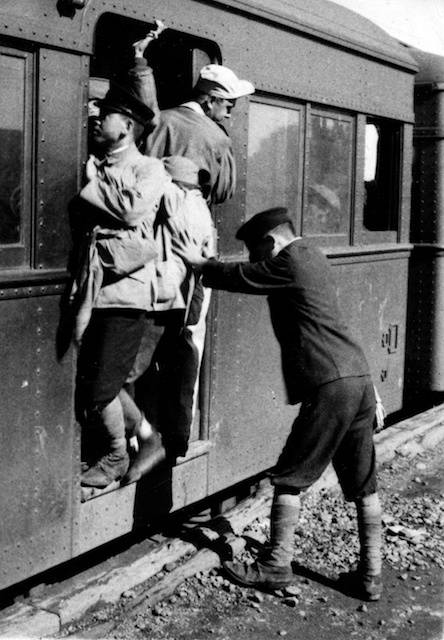

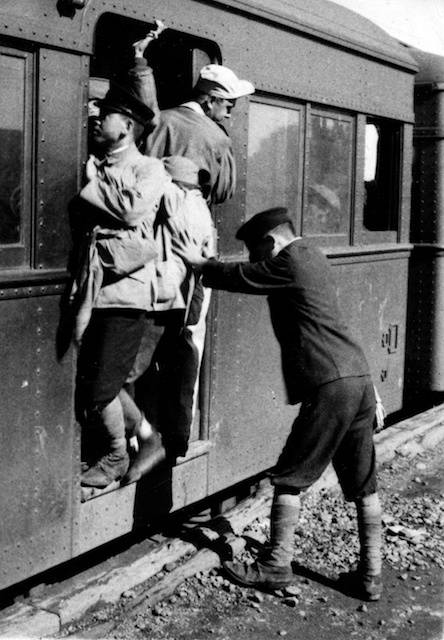

Yokohama suburban workers commuted as if there had been no defeat for Japan. This same work ethic helped them rebuild quickly after the war and will probably spur them to\r\nsurvive the quake and Tsunami.

Older commuters took the immediate postwar time to visit relatives in distant prefectures.

I wasn\'t yet a photojournalist, but l knew a good picture when I saw one in the finder.

I remember this work detail\'s one English speaker - the driver - commenting, \"we all make\r\n(he translated the yen) $9 each month, except me. I earn $8 because I do not do hard labor.\" They must have been organized by the Mayor of Milwaukee.

As her daddy lights his opium pipe, we see a survivor of the Tokyo incineration showing off her blouse with tiny red airplanes adorning it. Perhaps some designer\'s terrible homage to the B-29s which roamed their skies and destroyed their cities and thousands of lives.

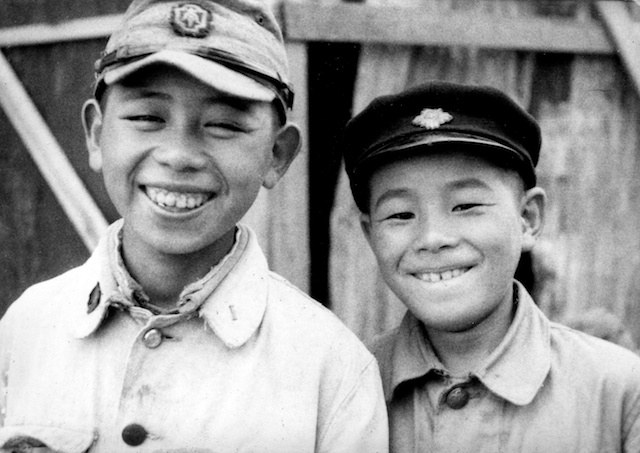

Ike and Mike, we called them. The one on the left because he looked like our commander of D-day in Europe, Ike Eisenhower, our President to be.

When you're making history, sometimes you have no idea you're doing it. Thus it was that on the hot morning of July 10,1945, I navigated a B-24 modified for 20 passengers, into Gatow Airfield in Germany. The passengers were American and English diplomats coming in to set up the Potsdam Conference - the one that would offer the Japanese a chance to surrender like "good little yellow enemies" (as our passengers saw it). The Japanese would decline the offer, their pride costing them 200,000 deaths and two A-Bombed cities: Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Six days after the death of Nagasaki, on August 21, they would belatedly accept our now-unrefusable offer.

Per my Gatow mission, the Nazis hadn't recovered enough from our bombing of their towers and runways to have rebuilt it in the four weeks since they had surrendered. Thus we had to land on grass without a wind-sock.They didn't even have an American in the tower. Just Russians. We were to be the very first postwar American plane to land at Gatow. In my broken Yiddish-German I spoke to the Russian running the tower. He told us to look on the grass for two Russian soldiers who would be carrying red flags as a clue for us which way the wind was blowing. This scampering duo (looking like UW Madison cheerleaders) arrayed themselves as at either side of an invisible goalpost- and guided us down on the grass between the chewed-up runways, like Meigs Field the night Mayor Daley would get pissed off at negotiations and send in his clowns with back-hoes.

Suddenly my calendar filled when some friends at the Pentagon pulled me back to Guam where a good celestial navigator was needed to navigate 56 members of General MacArthur's occupying team to take over Tokyo. A couple of weeks after we A-Bombed Nagasaki and Hiroshima, the circumstances of my 23-year-old life as a combat navigator in Europe and my patriotic (if adventurous) desire to bring our wounded home, found me stupidly navigating a DC-4 load of 60 people - the entire MacArthur Occupation corps - on a low level flight about as high as the Hancock Building over those first two radioactive bomb sites before we landed at Tokyo's Atsugi Airport to start buying up bargain kimonos for our ladies. It was a time when Japanese commuter trains would stop when they saw an American jeep, descend from their rails and, along with the wreckage movers and sorters, bow to us conquerors as we crossed the tracks at one bombed-out intersection after the next.

Radioactivity was just a word to us young flyboy hotshots. We weren't even warned against flying through it. "It" being science-affliction.

At this precise moment you Chicagoistos are all joining me in picking up some new, incomprehensible - but more deadly - airborne Japanese radioactivity. Dead, alive or in between, years from now you will all eventually know the story of how it happened to wonderful, uninvolved you. Who needed it? Certainly not your innocent children with their vulnerable bone marrow.

Here's how it happened to me, the reminiscence of a lucky old survivor who brought it on himself. You/we now are merely victims. Like victims of global warming so few of us believe applies to our busy lives.