From the Vault of Art Shay: Harmon

By Art Shay in News on Jun 8, 2011 4:00PM

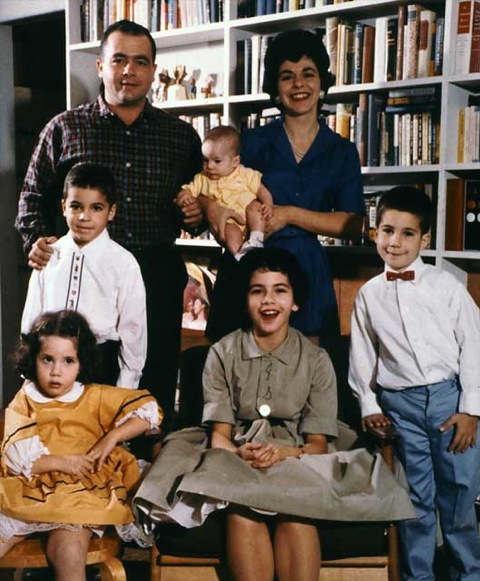

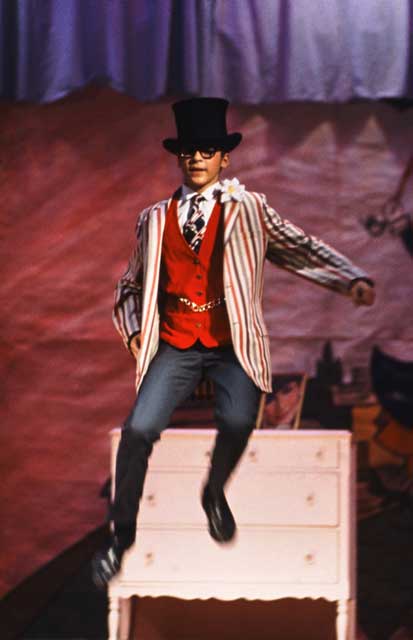

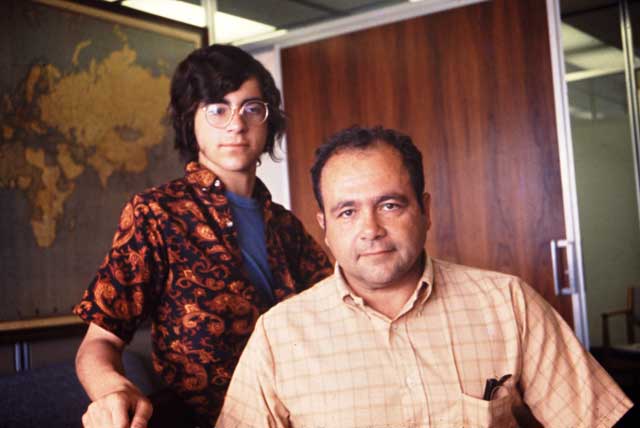

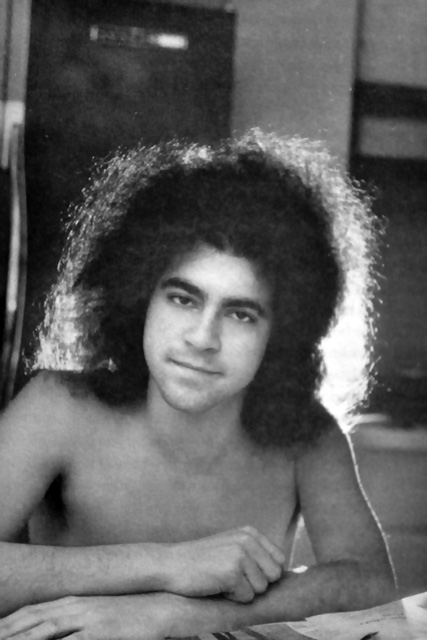

Florence and I belong to that terrible fraternity of parents who have lost a child. Our genius son Harmon was born on June 8, 1951 and yes, he would have been 60 today, the little guy who, before Bill Gates, invented a computer that randomly produced 200 words of poetry, who won four science fairs - one with an electronic skate he devised that followed his flashlight beam all over the gym. Our little guy who scored 800 out of 800 on both his SATs and whose benighted grade advisor at the U. of Michigan impelled him to quit school because he had declared the courses he was taking were not as challenging as the ones he’d taken at Deerfield High. More terrible we lost Harmon to murder in the Florida hippie jungles of 1972- just before Watergate. Presumably while hitch-hiking near Ft. Lauderdale. And more terrible still, we are amongst those grieving parents who never recovered a body to bury.

Years later, when an airliner crashed in the Everglades, drowning a hundred passengers in the green, impenetrable ooze that probably covers my son, Florence and I watched the heroic efforts of police, navy and the airline to bring some of the debris and any of the bodies, to the surface. Without saying a word we looked at each other grimly. We had unspoken, clung to the weird, wild, irrational hope that those boats and choppers, those flatbed cranes and God knows what other rescue devices, would somehow retrieve the long-dissolved body of our beloved son, and we’d go to Florida to claim the remains and bring them home for a proper funeral amongst his myriad friends and relatives who regarded him as special in the age just before the age of computers.

I imagine behind every one of the terrible TV and newspaper stories regarding the violent death and disappearance of loved ones during our myriad wrongheaded wars and violent peaces have precipitated feelings such as ours. Around a million of us are left who fought in WW2 of the 16.5 million who enlisted or were drafted. Our grieving parents and children, our faded snapshots and senior prom candids are sold for pennies at house sales to collectors of oddities. Continuity dies in a million dusty corners.

Do parents of a murdered child, or one taken by sickness or accident, imagine him or her forever the same age as he or she was ten, fifteen, twenty years ago his/her last day of life? Thirty nine years ago in our case. Do they see him getting older as I’ve imagined Harmon in the birthday week of my boy murdered at twenty, maturing normally in my mind year after year? Would he have turned him into the scientist we expected? We like to think of course he would, and would have found his success in a field his four successful siblings eschewed for professions of their own- law, journalism, photography… Of course. We still miss and humorously berate him for not being here to help us unfathom our computers. He whose death at 20 forestalled even seeing a manufactured computer.

Is it sick to mourn that Harmon never saw a laptop, or to weep for the unborn children he might have fathered to take places next to their brilliant and beautiful cousins? Yes, a little sick. And not much comfort. But avoiding these thoughts that screen up involuntarily is just as bad. And then you meet the parents of kids who committed suicide and grieve with them. Yes, suicide is worse.

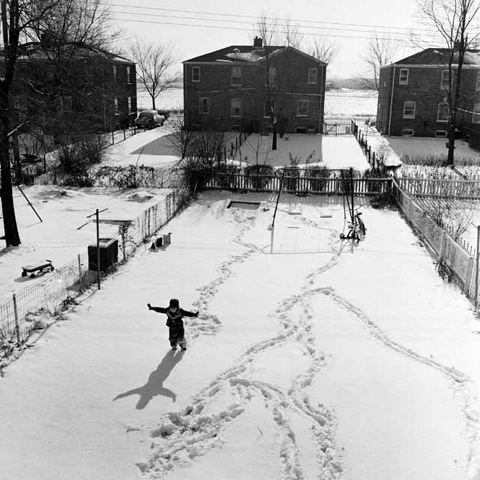

As I noted, today would have been Harmon’s sixtieth birthday. Nelson Algren’s tragic godson. A character out of an Algren or a Chekhov story. As am I, I suppose, a man whose head has lived with poor Harmon’s death half my life.. I had always thought, photographer that I am, we’d take out his kiddie snapshots and share his pictured joys with his children. But the snapshots merely map out the boundaries of my loss, and I find it hard to look at them without weeping.

I suppose the rational thing to do is permit yourself to be thrust into mindless activity while still smoldering with the outrage, the impotence, the unfairness of death. And gird yourself for death’s never-ending second strike: dealing with the ever-widening hole death stabs in your life and your sleep. And try not to take comfort in greater tragedies suffered by other people. Or invade your own privacy to mourn pathetically for those unborn grandchildren, for their cheery voices proudly passing on to me and Florence the breathless , happy details of their childhood. Their worn sneakers and tossed jackets sloppily filling the hallway. Never.

When Harmon was murdered two weeks before his twenty-first birthday, I thought back to the terrible Our Lady of the Angels school fire and I envied the distraught young Catholic couples who really believed the young priest who told them they would be reunited with their dead little boys in heaven. “God has taken him to stand by His throne in Paradise, and you will meet him again there.” The ten year old they had sent off to a school that with well meaning home boy fire officials, permitted rolls of spare linoleum, ultimately deadly when heated to be stored in basement hallways. My wife, who had been a member of a local synagogue, resigned after our tragedy because, though she believes in God and I do not, she found no consolation in religion. So Harmon is alive in me lives in me all these years later. This very moment I sit in the room, in the small space in which at sixteen in 1966 he invented his computer and his electronic roller skate.

When the life of a loved one stops, death starts, then continues and continues and continues in yourself until you die. .Or so it is with me. When a family of robins produced its own Harmon that year, in the tree outside my window, I photographed it for the Tribune’s Sunday magazine. My described envy of their feral joy at seeing their kid safely launched in the dangerous world brought me 50 letters from parents who had lost children and who also took comfort in the continuity of Nature.

If you can't wait until this time every Wednesday to get your Art Shay fix, please check out the photographer's blog, which is updated regularly. Art Shay's book, Nelson Algren's Chicago, is also available at Amazon.