Interview: The Siskel Film Center's Marty Rubin, Part I

By Rob Christopher in Arts & Entertainment on Jul 6, 2011 4:00PM

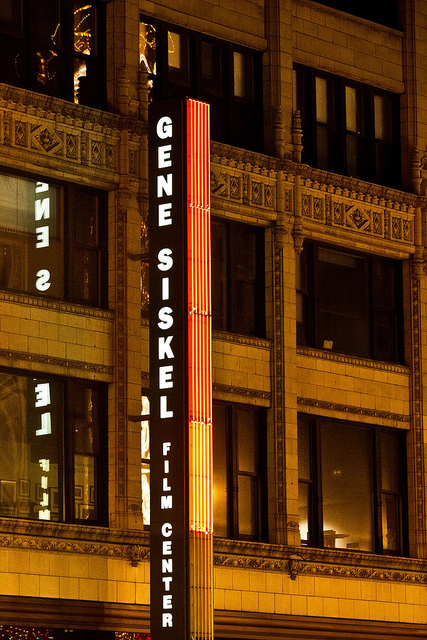

We've made no secret of our love of the Siskel Film Center, in our view the most consistently excellent place to see movies in Chicago. Aside from its ideal location, reasonable prices, and comfortable seats, one of the best things about the Siskel is surely the eclectic variety of programming. Retrospectives of major filmmakers, work from veteran and emerging experimental artists, local indie productions, and engaging documentaries are only a few kinds of the filmmaking represented each month in the Siskel's lineup.

So it was with no little excitement that we sat down to talk with Marty Rubin, Associate Director of Programming. Alongside Barbara Scharres, he's in charge of the nuts and bolts of putting the Siskel's schedule together, with all that entails. It's a position he's held since coming onboard in early 2000, not long before the Center moved from the Art Institute's Columbus Drive building to its new digs on State Street.

In our wide-ranging conversation we discussed everything from the Siskel's programming mix and what exactly programming consists of, to the "death" of 35mm film projection and 3-D.

Chicagoist: How did you get started in the movie exhibition side of things?

Marty Rubin: When I was a freshman at Yale University, there was a college film society. Almost on a whim, I applied for it, and to my surprise they accepted me. I became very active in the film society and eventually became the chairman of it. I’m embarrassed to say it, but I spent most of my college years not in classes but watching movies. It was a great way to educate yourself in film, because you could book the films you wanted to see. It was the heyday of art cinema. Basically, if you showed just about anything by Bergman or Fellini or Truffaut, you would pack the house. So you could use that to pay for showing films that weren’t as popular. It was also the heyday of auteurism. We’d just go through the directors—discover directors and try to see everything we could by them. It was quite exciting.

C: So you really came on board when the Siskel was starting to get more aggressive and ambitious about programming more things.

MR: That was totally a function of the new space that we moved into in 2001. Now that we had two screens to fill seven days a week, we had to be more aggressive. Really, that’s what programming starts from. The number one thing is that you’ve got to fill in all those blank spots on your schedule. It’s not, “Oh, I think I’ll see which of my favorite films I can play.” You don’t always have the luxury of picking a great film. It’s often a case of picking the least objectionable alternative among the films that are available to you. Probably the biggest misconception about programming is that you’re just selecting films that you like or that you’d like to see. That’s a small part of it. The main part is you have to find the films that you hope will work, which aren’t necessarily your favorite films. It’s nice when the film draws a big audience, but that doesn’t always happen. We always hope that the film will have some sort of impact, whether it’s with the general audience or the critics or the cinephiles or some subculture of people who will find it interesting. That to me is more important than whether it’s one of my favorite films or a film that I think is a masterpiece. Sure, that’s important, but it’s

more important to show films that connect with an audience.

C: Can you think of a few movies that you’ve shown that have been real successes that surprised you, that were really popular?

MR: Floored, which was the biggest success we’ve ever had.

C: That’s the one about the Board of Trade?

MR: Yeah. We had no idea. It was our biggest grossing film of all time. The people who made the film were very confident. And, you see, that’s the thing: a lot of films we show have the potential to find a audience. What it often depends on is that the people who are behind the movie—the filmmakers or the distributor— know the buttons to push to make the audience who will come to that movie aware of it. The makers of Floored really knew how to get that audience. I’m not that interested in the Board of Trade, but there are people out there who are very interested. We often show films that we feel are equally worthy, but some draw very well and some don’t, and we think a lot of that has to do with audience awareness, the target audience being aware of the film.

C: It seems like over the last ten years the Siskel has really evolved a programming mix that’s a nice balance between movies from local filmmakers, and touring stuff, and retrospectives. Is that a conscious mix or do you think it’s just kind of evolved?

MR: I’m glad you mentioned that. That’s very important to us: to have a mix of films that have different appeals. We don’t want to be narrow. We love it that we’ll be showing Muppets movies and some lesser-known Eastern European films at the same time. We think that’s wonderful, and it’s something we consciously try to do. We’d much rather err on the side of being too inclusive than too narrow. It doesn’t always work, but at least we’ve shown an interesting film.

C: Do you actually personally see every movie that’s in the lineup?

MR: Either [Director of Programming] Barbara Scharres or I, and usually both of us, see all the new films we show. But it’s not always possible to see a screener or a print beforehand, especially for some of the films in our retrospectives. Occasionally that also happens with a film in our European Union Film Festival—we haven’t seen it beforehand at a festival (Barbara goes to Cannes, and we both go to Toronto), but it’s been recommended by someone we respect, or it’s a film by an important director, like Godard or Haneke, so we know we’re going to show it no matter what. When we’re doing a retrospective, we try to see or re-see as many of the films as possible, so that the descriptions we write for our Gazette and website will be well-informed.

C: Is there any night of the week that you don’t go home after work and watch a movie or two?

MR: Hardly any. That’s very true. We get a huge number of screeners for new films, in addition to the films we watch for the retrospectives. Barbara and I are watching films constantly, on evenings and weekends. We refer to it as our “homework.”

C: Has your wife come to accept that? [laughs]

MR: Actually, she was a cinephile long before she met me. She doesn’t watch every film that I do, but she doesn’t mind, she watches a lot of them.

C: What would you say are some of your biggest challenges?

MR: A big challenge that we’re facing, that’s very much on our minds right now, has to do with the crisis over 35mm. This is something that Barbara, myself, and Brandon Doherty, who is our Technical Manager, are all very concerned about. I’ve been hearing these predictions almost from the minute I got here, in the early 2000's: “In two years 35mm is going to be dead. It’s all going to be digital.” And it didn’t seem to happen. But now it seems like it actually is going to happen. In the last year or two, 35mm prints have been disappearing. The distributors and the studios are not keeping up their libraries. They’re not replacing prints of old films, and often they don’t make prints of new films. They’re saying,“Why you don’t you just show them on digital?” We have had a policy forever that we only show films in their original format. We’ve had to compromise that recently, just because there’s no way around it. It really troubles me. I know there are great films in 16mm, avant-garde films by Anger and Brakhage, and there are films made in digital that are great, but basically to me 35mm is movies. There’s a magic to seeing a good 35mm print that’s well projected. I’ll often watch films here, even though I’ve seen them a million times, because we’ve found a good print and I know it’s going to look good on our screen. And there’s a kick, a real thrill to that. I guess that’s not going to disappear completely, but it’s going to become more and more infrequent. I find that very distressing.

When distributors come to us now with a new 35mm print of an old film, we’re more inclined than ever to show it, just for that reason. For example, The Makioka Sisters. Okay, we know that Criterion is bringing it out on home video in June, and that’s going to hurt it at the box office. The distributor didn’t offer it to us to play until July, but our feeling was: this is an important film, and they’ve made a new 35mm print of it, so it needs to be shown. And, basically, if we have any room at all, any new 35mm print of a classic film that’s shopped to us, we’re going to try to show it, because 35mm prints are becoming like a vanishing species. Even though I know the decline of 35mm is inevitable, I want to fight it as much as I can for as long as I can. To me it really changes the whole experience of watching movies and to some extent of being a film programmer. What’s important is not just that you program a good film, but also that you find a good print.

And often the programming is led by the prints. One of my first successes here was a series of westerns I programmed in the early 2000's. The prevailing attitude was, “Westerns? They’re out of fashion—nobody’s interested in them.” But I had noticed that there were a bunch of good 35mm prints available from different distributors that happened to be Westerns, so I said, “I’m going to do a Westerns series because I know they’re going to look great on our screen.” Not only was it a good series, but it ended up doing surprisingly well--probably because many of the films hadn’t been shown in such a long time, so there was a vacuum. But that’s an example. It wasn’t, “Oh, I love Westerns, wouldn’t it be great to have a Westerns series, let’s see what's out there.” It was, “Oh, there are a lot of good 35mm prints of Westerns. Let’s put them together in a series.” It’s much easier and more reliable to program “backwards” like that than it is to start with an ideal series, and then you run into rude reality and have to compromise. That happened with a Frank Tashlin retrospective I programmed here a few years ago. I thought it would be great to do a Tashlin series. I spent a lot of time scrounging up prints. And even though some of them were very good, like The Girl Can’t Help it and Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter?, we had to take some tattered prints because they were the only ones available.

C: Getting back to the digital question: obviously they say, digital projection is getting better and better every year, etc. etc. But it seems to me that the Siskel probably doesn’t want to shell out all that money every couple years to upgrade to the new digital system or whatever it happens to be.

MR: I don’t think that’s the main problem. We are going to upgrade from 2K to 4K, so we’ll be state-of-the-art. But for me the main problem is that, even if it is state-of-the-art, it’s still not as good. There was a digital restoration of Tommy that we showed last September in DCP, where the film comes on a hard drive, which is the highest-end digital format available to us. Tommy sounded great—the sound was as clean as I’ve ever heard here. And the image was very clean because there weren’t any scratches or dirt particles. It was very sharp, especially in the interiors and the nighttime scenes. But the daylight scenes, such as the scenes on the beach, had a dead quality. They didn’t have that glow, that luminosity, that 35mm has. And that was as good as we can show at this point—the highest end digital format that we can present. It sounded especially good, it looked nice, but it wasn’t 35mm. To me it’s not as good an experience. It’s not a real movie.

C: What about 3-D? Will the Siskel ever show 3-D?

Check back tomorrow, when we'll run the conclusion of our interview.