From The Vault of Art Shay: My American Gothic

By Art Shay in News on Jan 25, 2012 8:00PM

(Legendary Chicago-based photographer Art Shay has taken photos of kings, queens, celebrities and the common man in a 60-year career. In this week's look at his archives, Art reflects on his tribute to a piece of classic American artwork.)

In May 1944 I descended from the skies over Tibenham, England, having just navigated actor Jimmy Stewart's 703rd Squadron over flak-heavy Hamburg and back to the burgeoning Spring of our base in East Anglia. I was 22 and had a $97 black Model F Leica around my neck its small Elmar lens sporting an orange filter to darken the already dark skies over our tank factory target. I had shot most of the roll over the country of the camera's birth, but figured I had 8 frames left, which I was saving if we were debriefed by Major Stewart. I also wanted to ask him what kind of schmuck Cary Grant had been five years earlier when I tried to take his picture in front of Tiffany's and he denied being Cary Grant. "Oy wish oy werrre,"he'd said. (You read about it here.)

Suddenly, the engine sounds of a hundred swarming Liberators filled the sky. They were gathering for the day's second mission, circling, circling over an invisible Limey radio beacon, gingerly getting into squadrons of 12 and groups of 42. All filled with well-trained kids like me who had volunteered to save the country we loved; most of us with immigrant parents from Russia, Poland, Scandinavia and even Germany. We had been born to bloody the Nazis who seemed, like today's Middle Easterners and Republicans, poised to take over the free world with execrable bullshit words, self-directed cruelty, negation and other mindless tactics, plus incalculable cruelty. They were making soap out of people like me and using artful tattoos for lampshades. How lucky the NFL was to have missed WW2 at its worst.

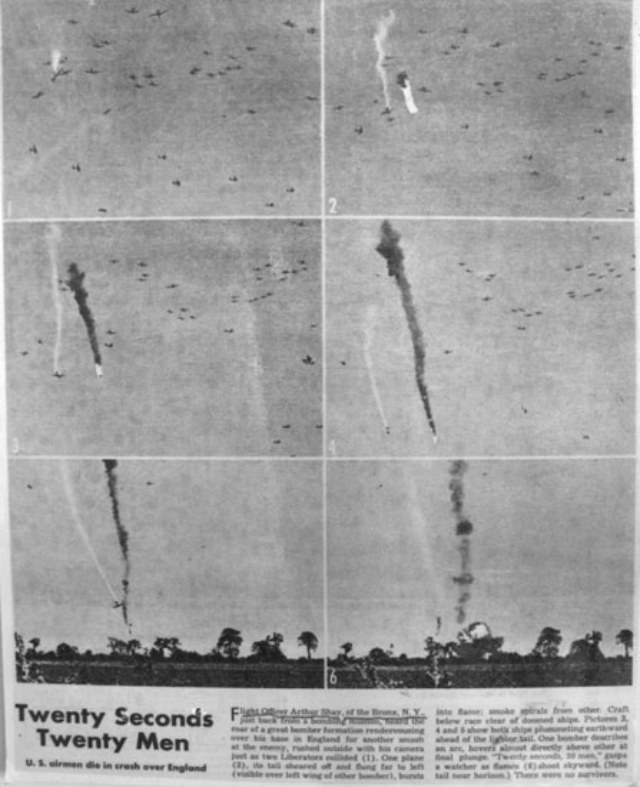

At the deafening engine sounds, I naturally raised my Leica (set at 1/500th of course) on the tarmac ringing the debriefing hangar. I managed to shoot one picture of a finder full of B-24s when suddenly two of them collided. Suddenly again, a panicking colonel collided with me, trying at first to cover my lens, then to knock it out of my hands! Having been a freshman quarterback at Brooklyn College in my brief months there, I kept evading the nutty colonel who kept yelling, "That's restricted. I'll have you court-martialed! Stop!" On the run — like a Manning who'd appear 65 years in the future, like the national racquetball champ I'd turn out to be — my feets did their stuff and I made six good heartbreaking pictures on the run Shoot, wind, shoot wind...documenting the two planes from collision to trailing the smoke of their doom all the way to the ground where both planes burst into orange bubbles.

Though I looked frantically as I shot, alas, I did not notice any parachutes. Look Magazine's headline said over the six pictures "Twenty Seconds, Twenty Men." Several heart-breaking letters arrived from parents and younger relatives of the lost fliers. Like Paul Stouffer's, the one that came today from Bozeman, Montana.

Dear Titles, Inc.Because of your affiliation with the great photographer Art Shay I am hoping you may be able to assist with this request. I am conducting research on a May 1944 accident which involved the collision of two B-24 bombers near Halesworth, England. In September, 1944, Look Magazine published 6 photos of the accident in a short article entitled "Twenty Seconds Twenty Men." The photos were attributed to Flight Officer Arthur Shay of the Bronx, whose biography as a WW II navigator makes him a likely candidate as the photographer on that day!

One of the pilots killed, Lt. John Hall, was from my hometown in Montana (he attended the same high school as Gary Cooper). I would be interested if the photographs still exist, as well as a statement or two from Mr.Shay regarding any recollection of this accident more than 67 years ago.

Thank you in advance for any assistance or direction you may provide in answer to this unusual request.

Sincerely,

Paul J. Stouffer

Bozeman, Montana

It's 1959 and I'm driving back from covering Khrushchev's visit to Roswell Garst's farm in Coon Rapids, Iowa. I was shooting for Life and my picture of K. holding up an American ear of corn, shaking it under the nose of our ineffectual Secretary of State, Henry Cabot Lodge, became Life's Picture of the Year. Another pushy fotog and I had rented a fake limo, adorned it with a fake credential number, and bribed a Des Moines cop $20 to get into the limo stream. Thus the late Johnny Bryson ( who lent his name to, I think, Frank Sinatra’s role in The Manchurian Candidate) and I were able to gain a full minute at every place Khrushchev stopped- as the other fotogs came out of the press bus. Schoolkids who had learned to hate the Russians because Khrushchev had sworn he'd bury us were let out of school by pressure from President Ike's administration to gather happily along Route 141 leading to the farm from Des Moines. Towns like Granger, Bryson and I affected Russian accents to shout "Vee vill bury you!" from our fake limo en route, which confused Iowans in towns like Perry, Bagley and Bayard.

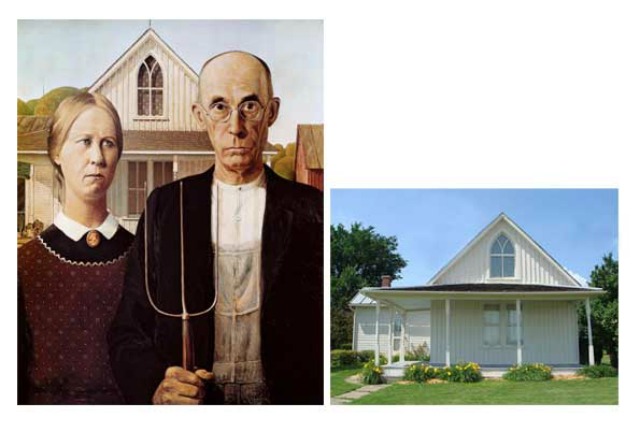

Suddenly I began to see buildings that looked familiar: Carpenter-style Gothic structures; spare, white, basic, like the one in Eldon, Iowa Grant Wood used as the background for his classic painting American Gothic. The 1930 oil on beaverboard creation is the Art Institute of Chicago’s most popular painting. Wood's models, he wrote in the essay that helped his picture win a bronze medal and a $300 prize, were "the kind of people I fancie, should live in that house". The woman was Wood's sister; the "farmer" his dentist!

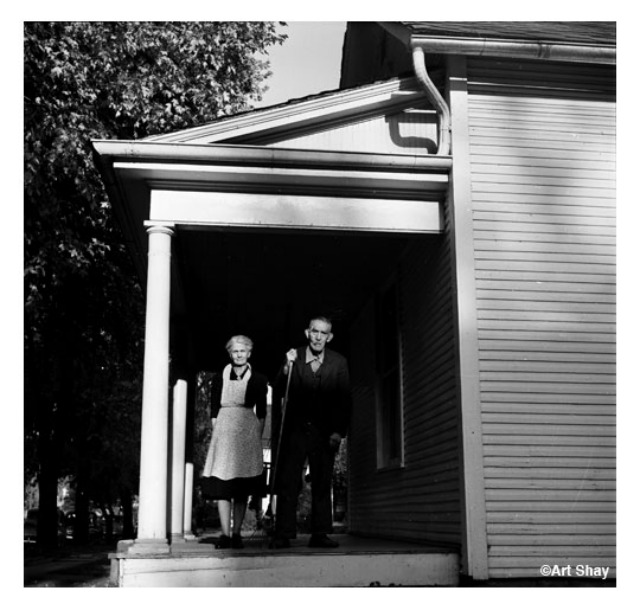

The picture has been much admired and satirized, but satire was far from my mind as I drove through Iowa, my Leica and Rolleiflex and telephoto Nikon on the seat beside me. I didn't even know that Grant Wood's house was in Eldon at the time, but somewhere along the southeastern route to Des Moines from Chicago, I slowed at a traffic light in the setting sun and found my own American Gothic couple in their own American Gothic house. I shot a single frame waved to the nice people and moved on.

I had always planned to seek out the parents of some of the kids who had died in airplanes adjacent to mine. Kids who had been decapitated by 20mm Focke Wulf cannon fire; others whose guts I had seen disgustingly panting their last few seconds. But the idea conveniently faded into my discomfort at facing them. Why, I could imagine them imagining, is this guy alive and our son dead? Why, indeed.

When I looked at the strong faces of these two Iowa farmers, a couple who had lived most of the lives I had so casually immortalized at the end of a sunny day—her face as resolute as any pioneer woman's, his eyebrow, bearing a scrap of bandage covering God knows what kind of minor wound—I realized that these were the kind of people I couldn't disturb with stale news of their late son or grandson, dead in yet another of America's endemic wars. It was, and still is, a cowardly corner of my soul--and it's a miracle that, thanks to a good-hearted writer in Montana, I get to pay this roundabout tribute to Lt. John Hall, whose last picture I took in May 1944, from half a terrible mile away, and still brings tears to my eyes for the 67 years of his life he didn't live, and I, by sheer chance, did.

I weep too for the unborn children of the 80,000 John Halls I survived in the 8th Air Force. We flew each mission into the teeth of an attrition rate of 71 percent. That is, the odds of not returning home were 4 to 1 in each of our (first) 30 missions. I then flew another combat tour on the secret Sonnie Project, in and out of Sweden, eluding the Nazi night fighters in Norway. (The midnight the war ended we were over Trondhem, Norway, and as we listened to the crowds celebrating in Paris and London- the lights 6,000 feet beneath us, came on after seven years of war — greens, yellows, reds and blues, and an ME 262 appeared off our wing, but I told you that story weeks ago...

Meanwhile, for Lt. John Hall and the others of my cadre gone too soon, I am proud to let my own happenstance American Gothic picture stand for a portrait of all bereaved parents and grandparents.

If you can't wait until this time every Wednesday to get your Art Shay fix, please check out the photographer's blog, which is updated regularly. Art Shay's book, Chicago’s Nelson Algren, is also available at Amazon.