A Wrinkle in Time Turns 50

By Tony Peregrin in Arts & Entertainment on Mar 19, 2012 6:00PM

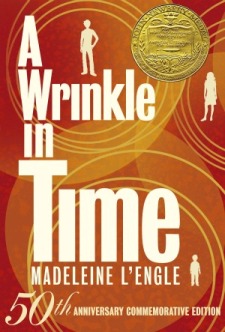

A Wrinkle Time 50th edition commemorative book jacket.

To commemorate the 50th anniversary of the young adult book classic, the archives has mounted a special exhibit featuring text from L’Engle’s 25th anniversary speech along with numerous rare photographs of the author.

The Madeleine L’Engle Papers date from 1919 to the present and feature well over 100,000 individual pieces, including the author’s typescripts, galley proofs, and page proofs for her published work, according to David B. Malone, MLIS, CA, an assistant professor and head of Wheaton College’s Archives & Special Collections.

“Archival collections—such as The Madeleine L’Engle Papers—are usually cataloged by type of material, keeping the principle of provenance in mind,” explains Malone, when asked how the large collection is organized. “We want to maintain any organizational structure used by the creators of the collection as it communicates things about them. If no discernible structure is apparent, archivists will impose a structure. Ms. L’Engle’s papers were well organized and are segmented by correspondence, book manuscripts, speeches and sermons, artwork, photographs, and several other categories and sub-categories.”

Today, the collection’s archivists continue to receive requests for materials from a wide range of researchers, from students working on school projects to publishers and scholars. Publishers and educators claim the enduring appeal of A Wrinkle in Time is largely due its unusual heroine, “outrageously plain” but likeable Meg Murry, its themes of non-conformity, and the author’s unapologetic references to modern science. Megaparsecs, anyone? (For the uninitiated, that’s a unit of measure for intergalactic space.)

Madeleine L'Engle. Photo courtesy of The Madeleine L'Engle Papers archive (Wheaton College, IL).

A Wrinkle in Time was rejected 26 times by various publishers and editors (one who famously claimed it was the worst book he ever read because it reminded him of the Wizard of Oz), before the manuscript was eventually published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux. This year, the same publisher has released new commemorative editions of the book featuring the original hardcover and paperback jackets, along with a new afterword by L’Engle’s granddaughter, Charlotte Jones Voiklis.

Chicagoist caught up with Voikis, 42, a resident of New York City (a tesseract was not required for the exchange, much to our chagrin) to discuss the archives at Wheaton College and why her grandmother’s writing continues to resonate with both young and adult readers.

Chicagoist: What is your favorite memory of your grandmother? The memory that is always right there, the one you don't have to dig or search too hard for?

Charlotte Jones Voiklis: My go-to memory of my grandmother is of dinner time and the evening routine at her house in Northwestern Connecticut. The house was usually full of family and friends, and after a day of working in her Tower [studio] and usually a trek to a brook in the woods behind her house, she'd take a bath, let my sister and I pick out a dress for her, and go downstairs to communally make a meal. Her salad dressing was outstanding, as was her spaghetti sauce which would simmer all day. After dinner, we'd take the dogs for a walk (“postprandial” was an early favorite word of mine) and then have a soiree (another favorite word) in her bedroom in her four poster bed with others gathered round. I don't recall how the dishes got done, and we still have a couple of her evening dresses—not gowns, but comfortable muumuu like things.

Chicagoist: What are some of your favorite pieces in the Wheaton College archives?

Charlotte Jones Voiklis: They have a terrific collection of photographs and a trove of correspondence and manuscripts that will make some future scholar very happy. They also have a wealth of audio.

Chicagoist: At one point, Ms. L'Engle stated that if something, particularly fiction, was not good enough for grown-ups, it was not good enough for children. What did she mean by that?

Charlotte Jones Voiklis: She never wrote for a particular market, never for children or for adults. She just wrote books. She was very frustrated by the way writers whose books get marketed for children are condescended to, as if they wrote for kids because they weren't good enough, or sophisticated enough, or clever enough to write for grownups. She didn't think it worked that way, and insisted that the techniques of fiction are the same whether you're Dostoyevsky of Beatrix Potter. And that children have very good bullshit detectors (though she would not use that word!) so a successful writer for children must not lie or speak down to children. Children are more open, she would say, to asking the big questions and that's what she liked to do in her writing.

Chicagoist: Children's book critic Leonard S. Marcus is publishing a book this fall titled Listening for Madeleine: A Portrait of Madeleine L'Engle in Many Voices. What can you tell us about the project?

Charlotte Jones Voiklis: Leonard interviewed lots of people who knew her, some well and some not so well, friends, other writers, colleagues, etc. I was interviewed, but I have not seen the book and don't expect to get a preview.

Chicagoist: Why do you think, on the 50th anniversary of a Wrinkle in Time, that the books in this series continue to be so relevant to readers, young and adult, especially considering the distractions of texting, games, and social media such as Facebook and Twitter?

Charlotte Jones Voiklis: I think they continue to resonate because they capture both universal, archetypal qualities, and [because] they are also very particular and immediate portraits of people, relationships, and feelings that people recognize. Also, the tesseract, and time and space travel is still unknown. It asks big questions about what matters, the nature of evil, agency, responsibility, family, love, and even though it doesn't answer those questions (beware of people with answers!) it's in the asking them that lights the way.