The Honk Heard Round The World: Goose Island One Year After The Sale

By Paul Schneider in Food on Apr 16, 2012 4:00PM

In March 2011, Goose Island Beer Co. shocked its hometown and sent ripples of disbelief across the beer world with the announcement that it had agreed to a $38.8 million acquisition by the world's biggest brewing company, Anheuser-Busch InBev. A year later, we wanted to find out where this Goose's soul calls home. Has it migrated down to Anheuser-Busch headquarters in St. Louis? Or even across the pond to A-B InBev headquarters in Leuven, Belgium? The answer we found is that, at least for now, Goose Island's soul is right here in Chicago.

Goose Island brewers were willing to speak freely about the identity and public perception issues they have faced in the market in the past year. They have grappled internally with the meaning of the sale, but have ultimately come to trust in the vision of Goose Island founder John Hall.

"Goose Island is John Hall and his legacy," explained brewmaster Brett Porter. "It comes from a real culture of Midwestern values, the things that make Chicago a great place to live: Innovation, hard work, and history."

John Laffler, manager of Goose Island's barrel-aging program, explained how John Hall was the pivotal piece of his decision to stay with the company.

"I was pretty pissy about the sale when it was announced," he admitted. "I asked myself, 'Is this right for me? Do I want to stick around? Can I do this?' Knowing John throughout the years, the passion he has for the company, the dedication he has to the people who work for him, that made it palatable. He's not going to sell out and head to Aruba. He's here every morning. He doesn't have to be. He could easily retire and walk away and live his life, but I don't think he would be happy. Goose Island is too important a part of who he is. Knowing that was enough to get me to stick around initially. Is it going to work in the long term? Is it not? Let's wait and see."

Porter agrees that the jury is—and should be—still out on the company and the beer.

"A year is not long enough to see what's going to happen to the beer," he said. "I think people should be paying close attention. What they'll see is that we're blossoming in a hundred different directions. I think people should hold us accountable to continue being as innovative as we are. Keep scrutinizing us. Demand better. That's what we're trying to deliver, and that's how we are here. We're as critical of ourselves and our beer as anyone else."

For now, some things are certain. Every morning, John Hall greets pub brewer Jared Rouben bright and early, then heads to his office at the Fulton Street brewery until he returns to the brewpub for lunch, and again around quitting time for a pint. As comforting as Hall's consistent, infectious enthusiasm is, nobody—not even Hall—knows how long the routine will stay the same.

The Honk

It was as if Goose Island was plucked out of the sky without warning by the most ruthless, calculating hunter. Soaring high with its flock of fast-growing craft brewers one moment, plummeting to earth the next. A team of Goose Island brewers was in San Francisco on a Saturday, soaking up the good vibes of the Craft Brewers Conference when a directive from the Fulton Street front office came in: be here for a meeting first thing Monday morning or don't bother showing up on Tuesday.

"We all knew something was going on. We didn't know what," recalled Tom Korder, Goose Island's innovation manager. "There was a lot of talk out there about what was going to happen. Is Greg [Hall] going to take over for [his father] John? Is the Craft Brewers Alliance going to buy the rest of the shares? Are they going to sell to somebody else?"

Nobody had to wait until the meeting to find out.

"I actually found out, as a lot of us did, on Facebook the morning they were announcing it," confessed Korder. Ouch.

Nobody was surprised that Goose Island made a big move; founder John Hall had talked publicly in the months before the sale about his need to raise capital to deal with quickly compounding capacity constraints. Yet despite the warning signs, almost everybody was shocked that Hall chose THIS big move.

The message from Hall was encouraging: Goose Island would remain in Chicago and retain control over brewing and management decisions. AB was getting into the craft game with Goose Island because the smaller, nimbler, more creative company could do things it could not.

Korder recalls thinking, "If what they're saying is true and if what John believes is true, we're still going to have control over what we want to have control over. They're not going to tell us to cheapen our beer, they're not going to tell us to change it. They're not going to shut down the Chicago brewery because that's not what they wanted to buy us for.'"

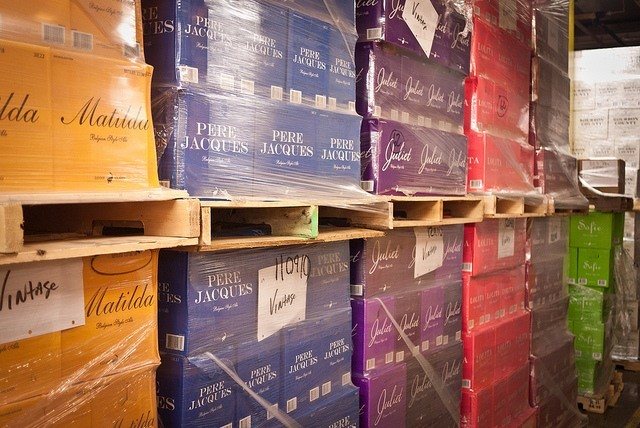

"We're making more specialty beer," explained Laffler. "They're not going to make Matilda, I don't think they even want to try. That's where our value is. They were looking for an entry into the craft beer world because that's where the dollars were. It's where the growth is coming from."

For John Hall and his top managers in the company, it was an easy decision.

"We had other opportunities and options to raise equity and increase our resources," said Hall. "For everyone that was involved in it, this was far and away the best for so many different reasons. There had to be some conditions and we agreed on those fairly quickly. I could have gone out and borrowed another several million dollars and done the thing myself, but where I was in my stage of life I was not going to do that again. We had some other brewing people involved too, but we ended up partnering with a company we already knew a little bit, and with the resources they had, and with the understanding that they were giving us the right to manage the brewery."

Despite John Hall's best efforts to reassure his employees and customers that Goose Island would keep on keeping on, Chicago and the craft beer world lashed out.

Cries of "sell-out" shrieked across Facebook and Twitter. Critics made overblown comparisons between AB and Hitler. Cynics wondered aloud when Goose Island's first sex-driven ad campaign would launch. Laffler received a text message from a local brewer friend asking when the first shipment of rice was scheduled to show up to the brewery. Impostor tweeter @gooseislandpr had a brief, but exceptionally snarky run on Twitter, championing new Goose Island brands such as zero-calorie Pepe Zero, lime-infused MaCHILLda, a 31.2-calore rehash of 312, and energy-infused Pere Jacked. Some worried about the quality of the beer and the innovation at the brewery with the impending departure of brewmaster Greg Hall, who was responsible for Bourbon County Stout and Matilda. Others didn't care if the quality faltered; ownership by a company known for its craft-stifling business practices was enough to spend their dollars elsewhere.

Laffler summed up craft beer's anti-AB sentiment succinctly. "AB is historically viewed in our community as a Goliath who comes in and decimates and controls through very aggressive buying and marketing practices, making it very difficult for craft brewers as a business model," he explained. "How true that is, that's an opinion, but it's a very widely held opinion. You grow up in brewing and everyone around you thinks they're the bad guys, and that we're all in this together against them. That's what you think to a large degree and you don't question it."

Korder confirmed that in his experience the response from consumers and retailers was intense. "The first six months were really bad. Even now with some of our new markets there's pushback," he said. "But ultimately we're in the same boat here at the brewery. If AB starts screwing up stuff, we're not behind it anymore. I am hesitant, I am skeptical. If the beer starts changing that's when I have an objection. That's all I can say. I can't guarantee that in a year it won't be different, that we'll have the same people in here. But for now, the people making the recipes and doing the barrel work are the same people doing it before the sale."

Laffler even feels the pressure at his favorite local beer haunts. There's always that guy who finds out Laffler is a Goose Island brewer and has to ask how the buyout is going. Laffler has resorted to telling people he's an applied biochemist if he senses the question of doom on the horizon. "There are downsides to everything and part of it is social," Laffler said. "It's easy for other craft brewers to discount us and say, 'You guys are owned by the devil.' We all like to pretend that everyone gets along and we're all in this together, and obviously that's not true. It's a story like everything else."

The negative reaction is easy to understand when other birds in the craft beer flock dealt with capacity issues without partnerships with Goliath. Goose Island's peers also confronted capacity issues last year, but several, like Dogfish Head and Great Divide, chose to withdraw their products from distant states in order to serve growing demand in nearby markets. Alongside those decisions, Goose Island's move appeared to many as just the opposite: was Goose Island turning its back on the city that turned it into a $38 million company, and throwing in the small and independent towel to boot?

Not to everyone. Hopleaf owner and unassailable craft beer advocate Michael Roper wrote to Beer Advocate that he was proud to continue serving Goose Island beers at his bar after the sale. "It should be about the beer," he plied, "not how big its maker is."

A Year Later

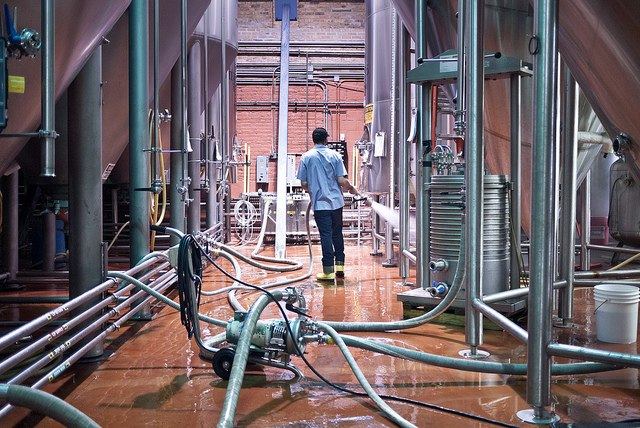

The benefits of the sale are easy to see. Production of Goose Island's year-round line-up has moved partially to large Anheuser-Busch breweries in Baldwinsville, New York and Portsmouth, New Hampshire. This move has allowed Goose Island to put 312 in cans and opened up capacity here in Chicago to brew greater volumes of more ambitious beers like Matilda, Juliet, and Bourbon County Stout. It hasn't come easy. Goose Island brewers work closely with their peers at the AB plants to dial in the beers in different facilities. The process involves Goose Island sending reference samples to Baldwinsville and Portsmouth, who then send samples of every batch back to Chicago for taste panels. Weekly conference calls get everyone talking about how to optimize—not necessarily match—flavors. Porter is happy with the progress so far. Recent batches of 312 and IPA are significantly better and closer to the original than the first off-site batches.

The strategy to open up capacity for what Goose Island does best is working. Matilda is growing so quickly that AB paid for a $1.3 million expansion to increase fermentation capacity by 1,200 barrels and construct an isolated room to deal with its special ingredients.

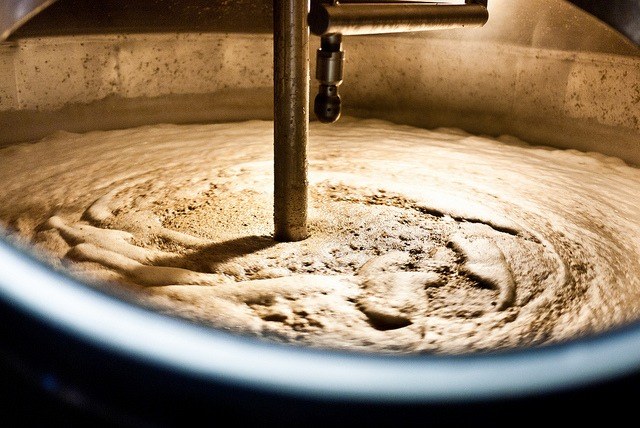

"With Matilda, we do a secondary fermentation with Brettanomyces that scares the crap out of most brewers," explained Porter. "We've stumbled along with it and the brands have grown faster than our ability to keep Brett out of the rest of the plant. We've been very lucky up to this point. We haven't gotten Brett in 312 or Honker's. We're at a spot where an infection now would be catastrophic. We're using so many organisms that other breweries wouldn't touch, that other breweries are scared of, don't have the experience to do, or are smart enough not to do. But we're neck deep in it. One of the things that separates our brewery from other places is that we've gone headlong into these projects and thought about the beer more than the possible consequences. You go around one time. You might as well have a hell of a good time."

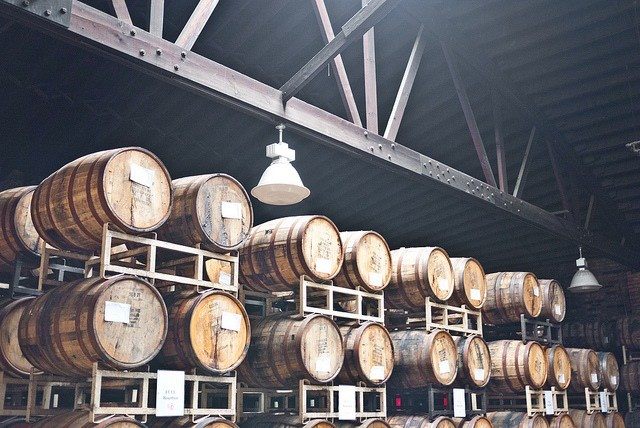

The calculated risk of innovation has been a hallmark of Goose Island throughout its tenure as Chicago's largest brewery, and was the driving force behind the development of the brewery's coveted Bourbon County Stout. The recent lease of a new barrel warehouse on AB's dime has allowed Goose Island to double the size of its barrel program and will soon lead to Bourbon County Stout being made available available year-round. This news will be received well by beer enthusiasts who sometimes wait in lines for hours just for the privilege of purchasing a bottle.

"We're growing at a very aggressive rate," reflected Laffler, wowed by the changes that happening around him. "We just got this whole warehouse and it's already full and we're saying, 'Great, now how are we going to double it?' You can't go to beer school for barrel-aging. It doesn't exist. I know, I actually called. We're always on the edge of knowing what we're doing. Over time we semi-figure it out, then we expand it radically, which makes it really exciting. We were doing that before the buyout, and now we're doing it even more aggressively. When I started here, we had sixty barrels. Now we have twelve hundred bourbon barrels and north of a thousand wine barrels."

Moving into the new barrel warehouse space ensures Goose Island will retain its status as the country's the largest barrel-aging program—for now at least. Others were creeping up on that title before the additional space was acquired.

With all the new capacity found in-house and in AB facilities outside of Chicago, Goose Island expects to produce 230,000 barrels of beer in 2012, up from 127,000 barrels in 2010. The increase over the past two years takes the brewery from a point where it failed to meet demand in existing markets to a volume that will allow the brewery to expand into nine new states this year.

"Last year we universally ticked off every wholesaler we had because we couldn't deliver enough beer. We don't have that problem this year," said vice president of sales Bob Kenney.

Has the marriage with AB met John Hall's expectations?

"It's played out the way we envisioned it," Hall reflected proudly. "I believe we've kept the same culture. We're taking advantage of the resources we didn't have before. We can see it a little bit in the marketplace already. We're continuing to develop new beers and be able to grow. We're coming out with new packages and are able to supply our markets. We have made a conscious effort to protect Chicago first and as a result we've shorted some out-of-state markets which hurt us a little bit. We're starting to regain their trust and in addition to it we're opening new states as we speak. Pretty much everything that we had hoped would happen has come to pass."

AB's resources go even further than helping with production capacity. Lab services such as gas chromatograph olfactory mass spectrometry are prohibitively expensive even for large craft brewers, but are available for Goose Island through AB. These tests help brewers identify and measure specific chemical compounds that are present in the aroma of a beer. At Goose Island, this is leading to greater understanding of and control over once-experimental techniques involved in brewing beers like Matilda and Lolita.

AB's engineering expertise ensures that equipment purchases and designs, like the Matilda room, are done right the first time. AB's insistence on safety compliance and the development of standard operating procedures makes the workplace safer and more energy- and water-efficient. The global network of brewers provides access to an unparalleled wealth of brewing knowledge.

But perhaps most important for the Chicago beer drinker, the beer is getting better. We at Chicagoist and Josh Noel at the Trib agree that Goose Island has done some of its best work since the sale. The Fulton & Wood line of innovation beers, available only on draft in the Chicago market, is

off to a strong start with Old Town Yard, a spot-on Helles lager made with hand-selected German ingredients, and En Passant, a riff on the old fashioned cocktail. En Passant is a mild rye ale with blood orange intended to be served alongside rye whiskey. As long as Goose Island keeps bringing its A-game to festivals and releasing one-time small batch beers, the local love won't fade.

Goose's Future

Looking ahead, Laffler remains uncertain about his expectations.

"If I was a large company purchasing a smaller company in a controversial realm," he posited, "I wouldn't change it in the first year. I would keep my hands off, let things die down, then start to do little things. I'm going to have an AB name tag. I have a badge card to open the door to the brewery. I think phone calls are being routed through a call center. It feels like we're losing some of the family-owned, local, independent part of the business. Is that balanced out by our ability to do things we want to do that we weren't able to do before? We'll see. Nothing's forever and change is inevitable."

Porter has a more optimistic outlook.

"What we want to have happen at Goose Island is to make so much of this special product that people can't or won't or don't want to make at other breweries that we can build a great big new brewery right here in Chicago," he said. "One of the first things that happened when I came here was that John Hall took me down to the river and showed the spot where he wants to build a brewery. That was exciting. What we really want is a big new brewery here in Chicago that is a cultural destination, which is what a lot of breweries have become. Damn it, I want people to know where we are. I want there to be a big beer garden on the river. I want people to come from far and wide to get beer they can perhaps only get in our beer garden and have a great time in this amazing place that I'm so happy to be living in."

Asked whether he believed AB would allow Goose Island to maintain the level of independence it has so far, Hall said, "I wouldn't be here if I didn't believe AB was going to let Goose Island continue to grow here in Chicago. My dream is to have a beautiful facility that we at Goose Island, all Chicagoans, and all craft brewers can be proud of. We're in the process of trying to put something together." Hall could not provide any more details about those plans at this time, but the announcement, if and when it comes, will undoubtedly be compared to the Lagunitas Brewing Co. plans to open a 600,000-barrel facility at 18th and Rockwell.

How does Hall respond to criticism about AB's business practices? Take the recent accusations from an anonymous craft brewer that AB is overloading wholesalers with their product in order to squeeze out competitors.

"It's BS," Hall shot back. "I'm privy to some numbers of how they manage inventory. It's not remotely true. Over the years, craft brewers have not had access to the market. There still are issues. But look at other consumer products, and how much variety do we have? The craft beer drinker has a lot more variety than a lot of other consumers. There's a disconnect between perception and reality here."

For those still not convinced, Porter challenges the simplicity of the Goliath analogy.

"I've always admired AB because of what they've done for the craft industry," he explained. "Most people don't know what the history of their insistence on the best materials has done for the industry at large. I don't think people know that the craft industry has been the silent beneficiary of the best possible ingredients. AB's support of the hop industry propped up the Willamette Valley and made sure the next generation could stay and work on the hop farms. You can say what you like about them, they've done a hell of a lot over the years to support and improve the quality of raw materials that go into all kinds of beer. The stupid young kid I was when I started brewing didn't know that. It took someone older and wiser to sit me down and tell me that one of the reasons the industry is so vibrant is because the big brewers have paved the way."

That reasoning may be difficult to reconcile with the default attitude of today's craft beer drinker toward AB. And it may be for good reason. Certainly, the people dedicating themselves to Goose Island everyday have had to find ways to come to terms with the sale. They all seem to agree on one thing.

"It's all about the beer," said Laffler.

"As long as it's good, keep drinking it," added Porter.

We'll toast to that.

Paul Schneider writes the local craft beer blog Chitown On Tap.

Michael Kiser of Good Beer Hunting contributed the photographs.