One For The Road: Happy 100th Birthday, Studs Terkel

By Samantha Abernethy in Arts & Entertainment on May 16, 2012 10:59PM

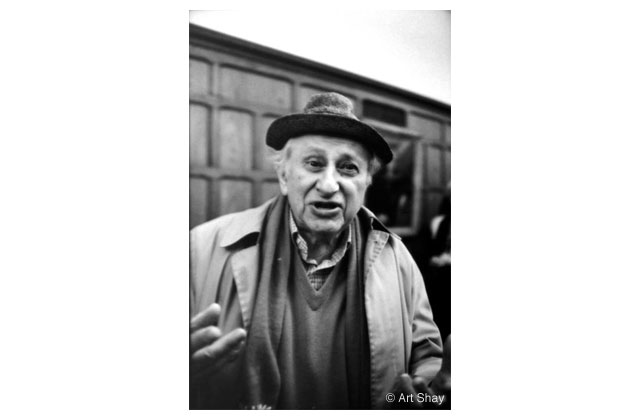

Studs at a 2005 literary function at the University of Chicago.

Studs Terkel was born on this date in 1912. To celebrate the man who believed every person has a story, we decided to each share our own. If you haven't read Studs's work, Working and Division Street are the obvious first choices to start reading. Please share your stories in the comments, and if you want to share them verbally, the Jane Addams Hull-House Museum set up a phone line to record stories about listening and about Studs as a part of the "Centennial Celebration." Check out the site to listen to others' stories, too.

Chuck Sudo

Neil Steinberg, in his Sun-Times column today, suggested that the tributes pouring in for Studs Terkel have "portrayed him as a rumpled man with a load of books under his arm" and a fondness for red socks and checkered shirts. I don't know what tributes Steinberg's been reading, but let's talk about that uniform for a moment, and Studs's shirt and socks were exactly that. Let's remember that Studs was, as Steinberg correctly noted, "an old school Lefty" who was blacklisted in the 50s and went on to become one of the greatest oral historians in this country's history. Studs was a tireless advocate for social justice and, while his tape recorder and typewriter gave voice to the voiceless, he literally wore his politics on his sleeve. And they were more in line with the protesters taking to the streets this week than the politicians beatifying him on his centennial. I'd like to think Studs would have found a way for the self-styled anarchists and the Bridgeport residents who so warily eyed them last night may have found some common ground with Studs as a mediator. He certainly would have chronicled their stories for this unique experiment in democracy we call America.

Kevin Robinson

I first found out about Terkel's seminal work, Working, when I was 11. The local Catholic high school put on the musical version of the play, and my dad took my sister and I to see the production. A few years later I found the book in a local library. I read that book cover to cover, though not straight through. Discovering the different jobs that people did (autoworker, organizer, grocery clerk, prostitute, typist) opened my young mind to the possibility that there were many different jobs out there, done by many different people, in all corners of our society and country. That someone could put together such an expansive and sweeping tome, that could give voice to people that I might not otherwise have ever known existed, let alone tell the story of their work lives with power and dignity changed the way that I saw both the world around me, but also the written word and how it could be used.

I'm no Studs Terkel; any writer in Chicago likes to think that he's carrying on that tradition each time they put pen to paper. But a little piece of what he wrote lives in my heart, and I hope, on my pages.

Rob Winn

I first learned about Studs Terkel when I was 16 years old at a Pearl Jam concert. (I would love to say it was at a punk show sponsored by the Daily Worker, but sadly it was not.) Eddie Vedder was playing the next night at a rally for Ralph Nader’s presidential bid and Studs was going to speak as well. I never made it to the rally, but I did pick up his latest book not too long after: Will the Circle Be Unbroken: Reflections on Death, Rebirth and Hunger for a Faith. It was extremely powerful coming from a man pushing 90 at the time. As a writer Studs showed me that it’s all about people, not inventing the most creative alternate universe or using words only a PhD would understand. Human experience is at the heart of every compelling story, that is how you show the world the triumphs and tragedies people experience. He has to love that we are sharing our own experiences with him for his 100th birthday.

Kim Bellware

At 17, my college-bound peers and I were getting all sorts of worked up about status: what schools were accepted to, what majors we would declare, and what careers we would have in four years. In a lot of folks' case, picking the "right" course of study or career path had less to do with what made sense to the individual and more to do with the impression it made on paper.

Around the same time, I first read Working, which turned the whole notion of our work defining ourselves on its ear. Absorbing Studs' observations about the meaning of work and happiness as told by lawyers and hookers and sanitation workers completely changed my outlook on "work." It was an eye-opener to have someone communicate that our work--our job that pays the rent--doesn't dictate who we are as people, or the meaning our lives have. That part is shaped by what we do in our communities, the stories we tell and how we treat one another.

Rob Christopher

Studs showed us that the ambient storytelling of our everyday lives, ordinary words from ordinary people, could be just as powerful and moving as anything in fiction. He showed that every stranger on the street possesses an interesting life, and he was gifted enough to be able to highlight those lives in a way that anyone could see.

My random Studs story. One day not so many years ago I was looking to get a quick haircut on my lunchbreak from work, so I went down the block to Supercuts. It was jam-packed of course. On my way back to the office I noticed this little sub-basement barbershop just down the street, the Medina Barbershop. So I decided to take a chance. The guy cutting my hair was a real old-timer. We got to chatting and it turns out he was Studs' barber! And Studs had just come in for his haircut the day before! During lunchtime. Since he died only a month or so later, I suppose that was his last haircut. I missed meeting him by only one day.

Samantha Abernethy

I was hesitant to tell my story because I didn't hear the name Studs Terkel until I was starting my graduate degree in journalism at Northwestern University in 2008, just a few months before Studs died. The native Chicagoans around me were appalled by my ignorance. I'd just moved to Chicago, and having grown up on a farm in Western Pennsylvania, I didn't know much about Chicago other than wanting to live there. I came to Chicago to take my writing seriously because I wanted to make a difference and tell a story that'd never been told. Without knowing it, I was already subscribing to Studs's philosophies of storytelling.

I discovered Studs's work while I was discovering Chicago for the first time, while I was getting my feet wet in the writing game. From writing about moose for a newspaper in Wyoming to writing about Rod Blagojevich for you folks here, I can't imagine doing it without knowing Chicago or Terkel's work.