A Primer On Peruvian Pisco

By Melissa McEwen in Food on Apr 24, 2015 3:30PM

You may have tried a pisco sour at restaurants like Tanta or La Sirena Clandestina. It's the gateway into the world of Peruvian pisco—a crystal clear spirit that at first glance looks a lot like vodka. But unlike vodka, pisco has a surprising smoothness and perfume-like aromas that make it an easy sip on its own or a perfect addition to many cocktails. It's no wonder it is becoming a standard spirit at bars and at home.

Pisco’s origins date back to the late 16th century when the Spanish conquistadores arrived in South America. Soon after, missionaries followed. Upon arriving, they realized no grapes grew in the region. As Johnny Schuler, Master Distiller of Pisco Portõn, explains, “No grapes means no wine. No wine means no mass on Sunday.”

So the missionaries planted their own vineyards and soon found that Peru was the perfect place for wine grapes to thrive. Schuler explains that overproduction coupled with the pain of transporting through the terrain with mules and llamas led them to distill it, an easy way to get a lot of alcohol in a small container. And pisco was born. The transformation of wine to pisco was only intensified in 1641 when Spain imposed strict taxes on wine imports from South America.

Cardenas and Schuler tutor a pisco cocktail class at Tanta (Photo by Melissa McEwen)

Peruvian pisco, unlike other spirits such as gin or vodka, is distilled to proof, meaning it’s only distilled once. Typically, spirits are distilled at least twice, usually to a high alcohol content first, which is then brought down by adding water, diluting the alcohol. But Pisco only needs one distillation and that's because of the grapes it is made from.

By Peruvian law, only eight grape varietals can be used in Pisco production, and they can only be grown in the south western part of the country. This area of Peru, as Schuler states, creates a “natural greenhouse” where the fruit receives enough heat from the sun, and cold from the night, to create grapes ripe with sugar. This is crucial because yeast digests sugar to create alcohol.

With so much in their wine, Schuler and his crew can watch as the yeast eats away at the sugar levels, keeping an eye on it until it reaches the desired 86 proof. Then, they can cut it and store the liquid in cement containers called cubas de guardia for five to eight months. This quick summary may make the pisco process appear easy, but it’s not. It involves plenty of work and time. For Schuler, each batch takes him about twelve hours.

There are three different categories of Peruvian Pisco. Puro, which is made with a single grape strain. Acholado, which is made from a blend of grape varieties, and Mosto Verde, which is considered the best version of pisco. Made when the wine is sweet (as opposed to when the wine gets dry like for a puro) it requires 50% more grapes, but leads to a rounder, softer pisco, which makes it a bit more expensive as well.

The most popular pisco cocktail both here in Chicago and in Peru is the pisco sour, which gets its velvety creaminess from egg whites. Admittedly it can be hard to see how the sticky egg whites could be transformed into something so drinkable. But at a media event we attended, brand ambassador Natalia Cardenas explained you have to think about it the way you think of another thing made with egg whites—meringue. The secret is to do a "dry shake" in the cocktail shaker, which means shaking all the ingredients without ice to build a froth before adding the ice. It's much easier than it sounds.

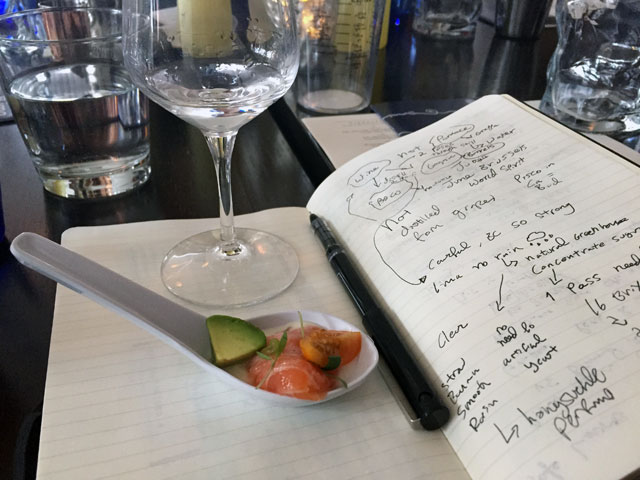

Learning, sipping pisco and snacking on cevinche (photo by Melissa McEwen)

Cardenas and Schuler also suggest trying pisco as the base spirit for your favorite cocktails. A margarita and a bloody mary we tried worked wonderfully with pisco, which brings out and complements the acidic ingredients really beautifully. At home we tried it with a negroni and loved how it complimented the bitterness of Campari (or Gran Classico Bitter). It became almost more bitter, but far more polished so the bitterness hits the taste buds in a totally different way. It's certainly not for people who can't handle bitter, but it certainly wasn't unrefined either.

Whether you see it at a restaurant or are just looking for a new spirit to add to your personal bar, Peruvian Pisco is a versatile and worthy contender with a spirited history.

By Ben Kramer and Melissa McEwen