The Story Behind Another 'Great Chicago Fire'

By Chicagoist_Guest in News on Mar 31, 2016 5:00PM

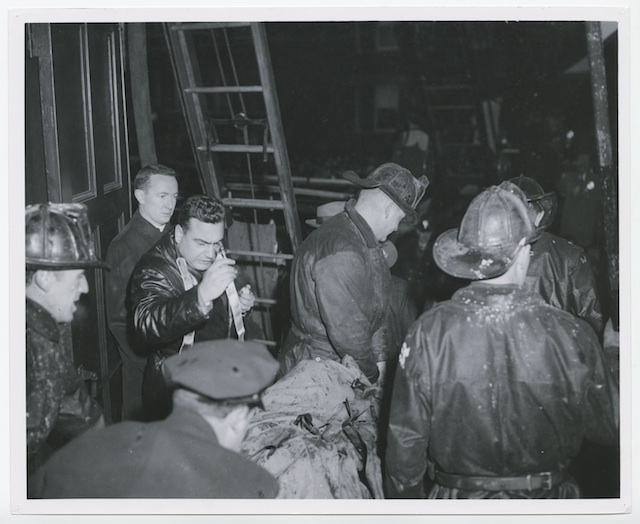

Firefighters on the scene of the Our Lady of the Angels School fire in 1958 (Chicago History Museum, ICHi-34978)

By Robert Dorjath

On Dec. 1, 1958—a cold and cloudless day in Chicago—90 people perished in a fire at Our Lady of the Angels School, in the predominantly Catholic neighborhood of Humboldt Park. Among the victims were 87 grade-school children and three nuns (five children died subsequently, in hospital, bringing the total to 95). It remains, to this day, one of Chicago’s deadliest fires; Chicago’s then-Fire Commissioner Robert Quinn said it was “the worst thing I have ever seen or will ever see.”

Nowadays, mention of the fire arouses an almost binary response. For those alive at the time, the school-aged especially, the tragedy is an indelible, cautionary tale. My God, they’ll say, who could forget? The nuns wouldn’t allow it. I warn my own kids. For others, born later and learning for the first time, news of the fire produces a kind of awed disbelief.

From time to time, while researching the fire, I’d uncover references to Our Lady of the Angels on websites for ghost tours, or in listings for so-called “haunted” places. It bothered me, at first. The interest felt lurid and cynical, somehow, though perhaps it’s unavoidable in cases in which scores of innocent people die sudden, ghastly deaths. Crowds gather likewise on Wacker Drive, at the site of the Eastland disaster, or huddle on warm summer nights in the drab alley behind the Ford Center, site of the former Iroquois Theatre and Chicago’s deadliest blaze. When the theater burned down, it killed 602, even more than the Great Chicago Fire.

Eventually, though, my opinion about the Our Lady of the Angels story changed. I came to agree the site was haunted. Not in any paranormal sense, certainly, but haunted by a painful and unresolved history, by a plague of crime and poverty in a once-prosperous neighborhood, and by unanswerable questions.

Firefighters inspect the wreckage of the Our Lady of the Angels fire (Chicago History Museum, ICHi-34979)

The fire started sometime after 2:20 p.m. It began in a trash can, in a corner stairwell of the school’s north wing. That section, built in 1910, had been the original church, outgrown by a thriving parish. It was later joined, of necessity, to a south wing via an annex. The result was haphazard: a two-story, U-shaped building surrounding a courtyard, bound tightly by Iowa Street, Avers Avenue, a concrete alley, and the Parish House and Rectory. From the outside, the brick school appeared durable and safe. The interior, however, was constructed almost entirely of wood and other flammable materials. The building had a single fire bell, located in the South Wing, but unwired to the fire department. By 1958, in midst of the baby boom, the school housed over 1,200 children. In many cases, its cramped classrooms were stuffed with 50 students or more, overcrowding almost unthinkable today.

Advent had just begun, a time for Catholics to rejoice and contemplate Christ’s return. The school day was ending. Everything seemed routine, but the fire had been burning, undetected, beneath the northeast stairs. Suddenly, a window in the stairwell burst and the fire erupted. Fueled by fresh oxygen, it stormed to the second floor. Today, modern safety codes insist on enclosed stairways with fireproof doors, but the school lacked both. The stairway was open to the central corridor, the sole means of escape for the six classrooms and 329 children there. Before anyone realized, the hallway was roiling with smoke. It was thick and opaque and deadly, like “huge black rolls of cotton,” as a nun later described it.

People inspect the Our Lady of Angels building after the fire (Chicago History Museum, ICHi-35438)

The second floor occupants were trapped. To attempt the corridor and stairs meant almost certain death. For most, the only option was to shelter in the vulnerable classrooms and wait for the fire department, while fire bore down. One quick-thinking nun blocked the gaps below her door with textbooks, while others gathered their students in prayer, determined to keep the frightened children calm.

In order to breathe, they opened the windows, which fanned the flames. In desperation, many jumped. Unfortunately, the fall was perilous. The school was equipped with an above-grade English-style basement, and the second floor windows were nearly 30 feet above the pavement. Neighbors ran to the school with ladders, but all came up short. At last, a battalion from the fire department arrived. Even so, the first ladder company on scene lost crucial minutes going to the wrong building, believing the fire was in the Rectory (911 as we know it did not yet exist, and the initial call to the fire department originated from the Rectory offices). Fire trucks repositioned, wasting time. They battered down a stubborn iron gate guarding the courtyard, as kids pleaded with them from above. More and more equipment arrived, but the fire, with its long head start, had the advantage.

Amid the chaos, the balance between life and death was sometimes a matter of luck and location. Occasionally, survival verged on miraculous. One child (now an adult in her 60s) has said she does not in all truth know, to this day, how she got from her burning classroom to the ground below. Several possibilities are plausible.

In the end, 200 firefighters were called to the scene. It was a five-alarm fire, which prompted the Department’s maximum response. It’s commonplace now, in serious emergencies—extra-alarm fires, school shootings, etc.—to establish a secure and remote perimeter, but such was not the case then. News spread quickly. The area surrounding the school was soon thronged with onlookers, including frantic parents hunting for their children. As the scale of the tragedy sunk in, a stunned neighborhood witnessed the worst at close range.

The loss of life was appalling. Ninety bodies were removed. The indelible image of the tragedy is of fireman Richard Scheidt. He’s too late, his coat drenched, his face hardened in pain. A lifeless, seraphic-looking boy hangs in his arms, limbs dangling, as solemn a depiction of agony as the Pieta of Michelangelo.

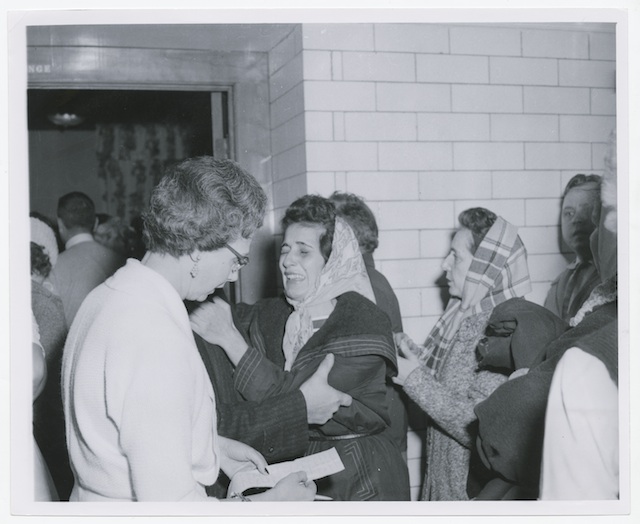

Parents at St. Anne's Hospital after the fire at Our Lady of the Angels (Chicago History Museum, ICHi-26743)

Almost six decades later, the fire remains an open case. Officially, it’s considered an accident. Although never proven, a widely-held belief still persists that the fire was set. From the very beginning, senior fire officials suspected arson.

A few years after the fire, a juvenile suspect was investigated for setting fires in Cicero. He’d been a troubled 10-year-old student at Our Lady of the Angels back in 1958, a fact which interested the investigators. Under examination he confessed to setting the school fire, and was given a lie detector test. He confirmed specific facts about the fire hitherto unknown to the public. The examiners felt convinced he’d told the truth. The case went to Family Court in 1962, heard by Judge Alfred J. Cilella. In court, the boy recanted. Judge Cilella threw out the confession, which he criticized, and dismissed the charge against the boy in the Our Lady of the Angels case. Cilella was a highly respected judge, and a deeply committed Catholic. He had private misgivings, reportedly, yet he found the boy innocent. Among other things, he feared for the youth’s safety if found culpable, and believed that the Catholic Church had suffered more than enough hardship over the fire.

There were other leads, and a second confession some years later, quickly dismissed. As it stands today, given the time that has passed, the source of ignition will likely never be known.

A priest blesses the body of a victim of the Our Lady of Angels fire (Chicago History Museum, ICHi-26694)

It’s essential to ask but impossible to answer. Why this school, at this time, and not another? Our Lady of the Angels School wasn’t particularly unique. In 1958, the same could have happened almost anywhere. Back then, a suffering community demanded a response, but even now, there are no easy answers. The questions only multiply.

Even if the above suspicions were true and somehow verifiable, it doesn’t explain why a 10-year-old places a match in a cardboard drum in the first place, or what causes him to become, if not a serial arsonist, then at least someone who intentionally sets fires. The perpetrator may have been emotionally troubled, abused or bullied. The parents may have missed the problem, or refused to face it out of ignorance, or fear or some other bewilderment which all parents experience, even in the best of circumstances. We’ll never fully know.

Besides, the fire’s human cost is why we care. Had 95 lives not been lost, particularly the lives of children and nuns—blameless in their deaths, and traditionally viewed as innocents—there would have been no tragedy or lasting legacy. Memory of the event, like the fire itself, would have died out long ago. The story scarcely feels modern, though in truth the fire occurred at the dawn of the space age, just a few years before Mariner 2 traveled to Venus and Kennedy challenged the nation with the moon. Yet, somehow, a building which housed over 1,200 children lacked a basic sprinkler system, proper fire doors, and an alarm connected to the fire department. The National Fire Prevention Association put it bluntly: The 95 deaths in this fire are an indictment of those in authority who have failed to recognize their life safety obligations in housing children in structures which are “fire traps.”

Funeral for the nuns who died in the Our Lady of Angels fire (Chicago History Museum, ICHi-35437)

In fact, the Chicago Fire Department had inspected the school, just months before the fire, and found it legally safe. Despite the findings, the building was an accident waiting to happen. The inspectors must have seen its deficiencies. At the inquest into the fire, senior officials insisted that delayed notification was the primary factor in the death toll. It’s entirely possible. In any case, to single out the Fire Department for blame is too simplistic. The fact remains, the school was constructed before the Chicago Building Code, and thus exempt from the requirement of basic fire safety features. Why, it should be asked, were public buildings, especially schools, exempt? The politicians who grandfathered in such buildings were to blame, but so was the electorate who placed them in power and corruption in Chicago.

Moreover, there was the overcrowding. The school was an antique tinder box brimming with children, far beyond safe capacity, which virtually guaranteed a loss of life once the fire started. Many blamed the Catholic Church, which readily packed the classrooms. Why did the church allow it? Like most religions, it goes to lengths to increase its numbers. The Church would argue it was only serving its mission, which in education leads directly back to Jesus. Regardless, few were turned away.

Ultimately, the causes of the tragedy were so myriad and complex, each contributing in some unquantifiable degree, that we might as well say life caused the fire—which is another way, I suppose, of saying it was “God’s will”—a gloss for events that totally overwhelm our understanding. I encountered that expression used again and again as I researched the fire.

The rebuilt Our Lady of Angels school today (left), and a memorial of the 1958 fire outside the current rectory building (Rob Dorjath/Chicagoist)

It’s hard to understate the long-term impact and significance of the fire. An entire neighborhood shared in the tragedy. Even if families survived intact, most of them had relatives or close friends among the bereaved, and the community never recovered. “It destroyed the neighborhood,” one survivor, a fifth-grader in the school at the time of the fire, told the Sun-Times. “It destroyed the people. Parents couldn’t cope. Divorces, all kinds of family problems [resulted].”

Formalized crisis counseling—a given today—did not exist. Instead, people relied on the Church to guide them, except in this case the Church, staffed by traumatized nuns and clergy, was inextricably entwined in the matter. The Church was anxious to move on, and, according to many survivors, discouraged discussion of the tragedy. While certain parishioners drew more deeply on their faith, others lost theirs entirely. In 1960, the Archdiocese dedicated a new school on the former site, completely fireproof and thoroughly equipped with all the modern safety features—though it should be noted that none of the technology was newfangled, or non-existent at the time of the fire. When the new school opened, the majority of families returned, but many others decided to move rather than face daily reminders of loss.

The new Our Lady of Angels School, with new safety features (Francis Miller/Life Magazine)

Others fled the Humboldt Park area due to the rampant, predatory practice of blockbusting, whereby whites were panicked into dumping their homes by unscrupulous, race-baiting real estate speculators, who then flipped the properties at exorbitant rates to middle-class African Americans. In time, with repossessions and foreclosures, racial unrest and lack of opportunity due in part to racist hiring practices, the area grew poorer and poorer.

By 1990, with dwindling attendance, the Church permanently closed Our Lady of the Angels parish, and later the school, which is now a charter. As reported recently, Chicago remains deeply segregated, not only by race but by a new measurement, the Distressed Communities Index. These days, communities in the former Our Lady of the Angels parish—which drew from Humboldt Park, Austin, and West Garfield Park—rank in the highest decile of the index, which measures economic hardship and inequality.

Officially, the Our Lady of Angels fire was extinguished at 4:19 p.m. on that cold December day in 1958. But in a sense, it hasn’t been put out. The specter of the fire lives on in that distressed neighborhood, though many residents are unaware of the history and had no hand in writing it. Likewise, it lives in the hearts of those who survived the ordeal. They remain closely bonded to this day and want their story remembered. The survivors and the Archdiocese honor the anniversary each December, though the participants gather at the nearby Holy Family church instead of their former church, which is now a mission. The Mission of Our Lady of the Angels—an ongoing Catholic presence in the neighborhood—provides food, clothing, after school programming, and other material support for those in greatest need.

If nothing else, schools in the United States today are safe, at least from fire. But progress took a calamity. Following the Our Lady of the Angels fire, sweeping changes were made across the country to prevent another tragedy like it. Today, the death of a child by fire in a K-12 educational structure is nearly unheard of. But the price of safety proved high, especially for the Chicago parish that bore the cost. John Raymond, who survived the fire by jumping from a second-floor window, knows the fire’s price well. He’s the son of the school’s former janitor, James Raymond, a hero of the Our Lady of the Angels fire who rescued many children.

“Whenever I see an old red-brick school I think about it,” John said, speaking to the authors of To Sleep with the Angels. “And there are a lot of red-brick schools.” He added, “It’s a sacred place. You can feel something when you drive by there. It’s a part of history.”

Further information

For additional background on the Our Lady of the Angels Fire, read (or visit) the following sources used in this piece:

* To Sleep with the Angels, by David Cowan and John Kuenster

* Quarterly of the National Fire Prevention Association: The Chicago School Fire, January, 1959

* The Fire History Museum of Greater Chicago

* Archives of the Chicago History Museum

Robert Dorjath is a native Chicagoan and a fiction writer. He is currently working on a novel inspired by the Our Lady of the Angels fire.

Correction, 1:15 p.m.: Our previous headline said this fire was deadlier than the Great Chicago Fire. It was not.