'Searching For John Hughes' Author Jason Diamond On The Chicago Teen-Movie Master

By Stephen Gossett in Arts & Entertainment on Nov 28, 2016 5:29PM

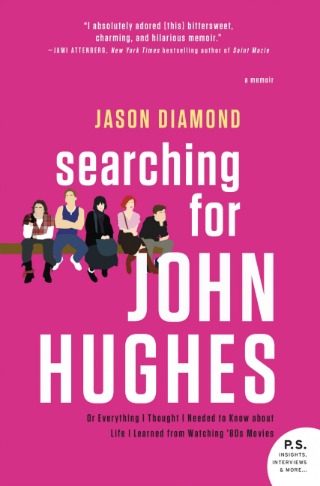

Harper Collins

Whatever their faults, Hughes' '80s coming-of-age totems like The Breakfast Club, Ferris Bueller’s Day Off and Sixteen Candles looked upon teenagers as a real audience—heavy on empathy, light on patronization—rather than simply as a consumer bloc. He also had a deep, abiding faith that, despite our youthful neuroses and real-world hardships, the Rockwell-ian happy ending was always attainable. (Stanley Kubrick once compared Hughes and frequent collaborator Anthony Michael Hall to Frank Capra and Jimmy Stewart.) That combination—part realism, part aspirationalism—was especially potent for of-a-certain-age natives of the Chicago area, which doubled almost as a character of its own in so many of Hughes’ films.

That was particularly true in the case for writer Jason Diamond, a Skokie native and lifelong fanatic of the director’s work. “Fanatic” might not be a strong enough word, in fact. In Diamond’s wonderful new memoir, Searching For John Hughes, the director’s films seem to permeate the writer’s entire existence. The films’ misfit compassion offers succor from Diamond’s brutal childhood, marked by parental abuse and homelessness. The Hughes promise—that despite the psychological pain native even to the tony North Shore that Hughes and Diamond both called home, it’ll still all work out in the end—continued to drive Diamond post-adolescence. After leaving Chicago for New York City, he spends year after year trying to compile the definitive Hughes biography—despite having no agent, little experience and zero access to the infamously reclusive filmmaker. Even as Diamond grows out of the always-problematic “art as roadmap for life” concept, there’s a, dare we say, sense of coming of age that Hughes might appreciate. The fact that Diamond arrives somewhere that looks and feels quite a bit different from Hughes’ fictional Shermer, Illinois universe only makes it more resonant.

We caught up with Diamond to talk about the teen-movie master, Hughes-related pop-culture tourism in Chicago, lack of diversity in Hughes’ characters and what still holds up in the director’s oeuvre.

Chicagoist: That combination of wounded realism plus sentimental uplift is so central to Hughes, but it seems like it's less prevalent. Where do you see his legacy today?

JASON DIAMOND: I think we’re probably looking for more straight-up realism, and I think that’s important in a lot of ways. I do sort of miss the sappy, happy ending. But I think directors and writers—and this jumps off Hughes—they don’t want the Seinfeld or Sopranos problem, where people get pissed off if something is left off. So they try to make it clear as possible: this is what happens. And I think that coming into play for pop culture was a good thing.

But that said, I think his impact is definitely noticeable when you read books by writers like John Green or Rainbow Rowell, a lot of Young Adult stuff that takes a real look at teens—or at least as real a look as a 20- or 30-something-year-old writer can muster. It gives a more realistic view of what its like to be a teenager. And there were obviously writers before John Hughes, like Judy Blume and J.D. Salinger, exploring that territory. But that’s where I see his work carried on most, in my mind.

Jason Diamond

JD: I don’t think I did. You know, I was a kid growing up in the ‘90s obsessed with movies from the ‘80s but also, at the time, punk rock from the '70s and '80s—all things that weren’t of my time. So it all kind of felt like my own thing. Obviously his movies mean a ton to a lot of people, but at the time, it just felt like my escape. So I didn’t have huge expectations for the movies. I didn’t think, these are letting me down. I just felt compelled to watch and think about his films because I wanted these happy families, happy friends and mowed lawns and sunny skies. I was looking more for the end goal than what was in the middle.

C: You write a bit in the memoir about the lack of diversity in Hughes' films. Do you think that could prove a fatal flaw for potential future audiences?

JD: It’s really hard to say. You have to look at the 60 years of film history prior that is also dominated by white actors and actresses. So will it damage his reputation anymore? So much of film history is so whitewashed, so it’s hard to say. But I do think it can open new ways to reinterpret or rework those kinds of stories to be more diverse—like Dope (2015), which kind of pays tribute to John Hughes in a way. So I think it’s more about moving forward than saying his films don’t work anymore, because that’s so much of film history, unfortunately.

C: You visit a lot Hughes landmarks throughout the book. There’s a particularly emotionally resonant moment in which you stop at the Home Alone house, in Winnetka. Did having these locations intersect with your own personal history change how you think about pop-culture tourism?

JD: I’m weirdly obsessed with stuff. I’ve written about walking in places where certain authors have lived. I’ve always been fascinated by that—but not the prepackaged, get on the bus and we’ll show you the Home Alone house experience. I’ve always been interested in exploring what this place means and why it’s important.

I will say I thought the Ferris Fest that took place over the summer in Chicago was pretty cheesy. I read that the people who organized it were on WGN, which made me happy, that they were on WGN. But the host asked if the organizers were from Chicago. And when they said no, the host took them to task for that. And I was like, yes! So I felt weirdly justified. But going to see locations, either in Chicago or elsewhere, that might resonate for some reasons. I’ve driven like a creep past that Home Alone house more than a few times. I’m not going to stop doing that, unless they call the cops—which actually maybe they should.

C: In the book, you reflect often about how you used Hughes' films as a roadmap for your life, for better or worse. It seems like Hughes invites that sort of impulse.

JD: I realize it was me. It was my own obsessiveness.

C: But don't those classics of his breed obsessiveness?

Certain directors might, but I’m not so certain he does. I’ve met people who spend their whole careers writing about Francois Truffaut or Stanley Kubrick, but he’s not considered on those levels. I sort of see why and I allude. For me, I saw something I liked, something that literally looked like my backyard, and it felt attainable. What I realized was you cant rely on music or movies or books to help you figure out how to live life. If you took every pop song to heart, you’d be a bleeding romantic with a crushed heart every five minutes. If you want to be in a John Hughes film, you’d have to be a well-to-do kid, maybe from Glenview, and you’d have to look handsome or pretty, but I unfortunately don’t have those things going for me.

You talk about watching Planes Trains and Automobiles every year for Thanksgiving. Is that tradition continuing this year?

JD: I watched it the other day, actually ahead of Thanksgiving. I cheated because I wrote something about it. But scribbling along to it isn’t tradition, so I’m going to make everyone sit down and watch it with me. The day after, I think I’ll watch Home Alone. Then maybe a full marathon.

C: How did it feel different than in years past compared to when you just re-watched it?

JD: It was actually last year that was really interesting. Because I had my wife and best friend with me; and my wife was like, please don’t make me do this again. That meant a lot to me because I had just finished writing a bulk of the book and was really thinking about how this was a part of my life for so long. But it’s my one tradition that people can now share with me if they read the book. It means a lot that I got to create my own tradition and that’s a really beautiful thing.

C: Have people reached out mentioning their own similar tradition?

JD: Yeah, people emailed, tweeted. I know Hughes is important, and there’s an entire generation of people who are like, I went to school on those movies, or Home Alone 2 was the first movie I saw in the theater. That’s part of the magic of John Hughes, but to find that other people have these insanely deep connections—I suspected they were there, but it’s comforting to find out there are so many others with similar feelings. Like when you’re a kid and you see someone else in a punk shirt. ‘Oh, I’m not the only one here who like Crass.’

'Ferris Bueller's Day Off'

C: Which films from Hughes' golden area hold up for you, and which do you now find wanting, if any?

JD: I’m not a fan of remaking movies, but I would love to see someone make a stage adaptation of The Breakfast Club. That would be incredible to see. Films like Woody Allen’s Manhattan or Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing, I think Ferris Bueller is that to Chicago. So whatever aspects end up dated, to me it’s always going to be the Chicago movie. Nobody’s ever going to make a movie like that, from the premise, to the characters, to how Hughes highlights Chicago in such a beautiful way. And Home Alone stands out. I think that was where John Hughes said to (the film’s director) Chris Columbus, ‘You’re the next in line to do this.’ When you look at the huge success of Home Alone and Home Alone 2, then what Columbus did afterward—with Mrs. Doubtfire and several Harry Potter movies, which is one of the most important cultural touchstones in decades—that feels important. And it’s still a really good film, too.

The ones that don’t hold up. Despite its problems, Sixteen Candles has some good parts. Michael Anthony Hall is pretty funny. That '70s/'80s National Lampoon-style humor resonates for a certain generation; I’m not so sure it really sticks today, even if it has some great moments. Pretty in Pink holds up—nostalgia and those '80s clothes help. But I also have such a weird powerful connection that it’d be hard for me to damn any specific movie. Maybe Flubber, which he wrote. That’s not so good. (Laughs)

C: Have you thought about what John Hughes would think of your book? Even despite the subject matter it seems like an arc he might appreciate.

JD: Yeah, in a weird way, I’ve thought about it. There was actually a documentary from a few years ago, Don’t You Forget About Me, in which a Canadian film crew goes to Lake Forest, trying to get John Hughes to read their teen-movie script. Of course, he just sends it back, and you never see him. I thought about that whenever I’d dwell on what he’d think about the book, if he were still alive: I’m not trying to get anything out of him by writing this. This is a tribute and a way of saying thank you. It sounds so clichéd and angsty, but I don’t know if I’d be here if I didn’t have those movies to rely on. It’s to say, John Hughes, you meant a lot to one person. He meant a great deal to a lot of people, but not many were psycho enough to write an entire book about it.

Searching for John Hughes by Jason Diamond is available on Tuesday, Nov. 29 through Harper Collins. Diamond appears with guests at The Whistler on Monday, Dec. 5 (7 p.m.) for the Chicago book-release party.