Remembering When Chicago Was The Face Of The Flag Desecration Debate

By Stephen Gossett in News on Nov 29, 2016 10:09PM

Photo: John Burdumy

Donald Trump sent out a Tweet this morning. A lot of new stories will likely continue to begin with that premise, and understandably so. But this one took direct shot at a bedrock national ideal, the First Amendment’s freedom of speech.

Nobody should be allowed to burn the American flag - if they do, there must be consequences - perhaps loss of citizenship or year in jail!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) November 29, 2016

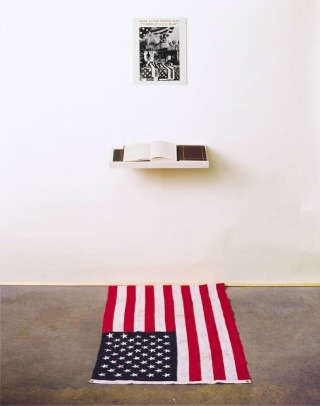

'What Is the Proper Way to Display a US Flag?' / Dread Scott

Back in 1989, artist Dread Scott, then a student at the Art Institute of Chicago, ignited a political firestorm when the school displayed his “What Is the Proper Way to Display a US Flag?” work. The exhibition included photos of South Korean students burning the American flag. Underneath the display was a book in which viewers were asked to contribute their thoughts about the subject. The twist? In order to write in the pages, you had step on an actual American flag, splayed unceremoniously on the floor.

Then, as apparently now, the Republican establishment was livid. President George Bush Sr. himself chimed in, calling the work “disgraceful,” and GOP members of the national legislature looked to criminalize such acts.

The New York Times wrote in 1989, following the exhibition’s closing:

"Senator Bob Dole of Kansas, a disabled veteran of World War II, introduced legislation today to amend Federal law to make it a crime to display an American flag on the floor or the ground. It passed by a vote of 97-0. ''Now, I don't know much about art, but I know desecration when I see it,'' said Mr. Dole. A similar bill has been introduced by Representative G. V. (Sonny) Montgomery, a Mississippi Democrat."

Here in Chicago, things got even more bizarre, with a famous, long-serving local pol doing a proto-Clint Eastwood. The Tribune reported in 1989:

On the council floor, Ald. Edward Burke (14th) held an imaginary conversation with Benjamin Franklin informing him what had happened to "Betsy Ross' flag."

The Chicago City Council at large got in the game, too, passing an ordinance "forbidding mutilating or defacing the flag," the Times wrote.

(As mentioned above, the Supreme Court ruled such measures unconstitutional, most recently, and not coincidentally, also in 1989.)

Tony Jones, president of SAIC back then was the adult in the room, it seems. He addressed the artist and the angry demonstrators who formed around the school at the time, according to the Trib:

"(Scott) has manipulated the situation to the advantage of the work. It does make you question your patriotism. And for all those people that were marching around the school yesterday, it's a reaffirmation — of belief in the flag, in their values, in their national symbol."

Today, Scott continues to create art, although he bases his practice in New York. His work is still oftentimes confrontational and charged with righteous anger. (Last year's "A Man Was Lynched By Police Yesterday" drew quite a bit of attention, using the flag medium in a different yet equally political way.) But the "Flag" he created in Chicago will always precede him—and in the way it pointed toward an effective truth-to-power art-as-protest punch, it remains sadly pertinent today as then.