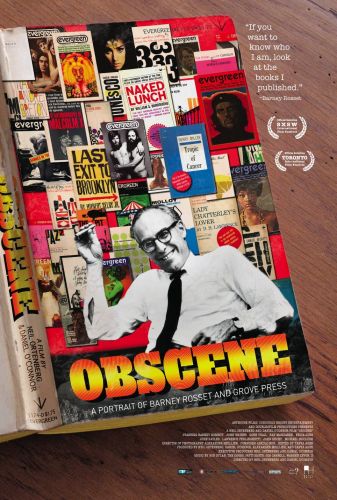

Interview: Obscene co-director Neil Ortenberg

By Rob Christopher in Arts & Entertainment on Oct 31, 2008 4:30PM

Barney Rosset is the most famous person you've never heard of. But you've probably heard of some of the authors he's published: Samuel Beckett, D.H Lawrence, Henry Miller, Jean Genet, Malcolm X and William S. Burroughs just to name a few. Born into a wealthy Chicago family, he grew up here in the city and attended the Francis W. Parker School (where one of his classmates was filmmaker Haskell Wexler).

Barney Rosset is the most famous person you've never heard of. But you've probably heard of some of the authors he's published: Samuel Beckett, D.H Lawrence, Henry Miller, Jean Genet, Malcolm X and William S. Burroughs just to name a few. Born into a wealthy Chicago family, he grew up here in the city and attended the Francis W. Parker School (where one of his classmates was filmmaker Haskell Wexler).

After a stint in the armed forces he ended up in New York City, where, at the age of 29, he took over a dormant publishing concern named Grove Press. It wasn't long before he began to turn it around by publishing controversial books that no one else wanted to touch.

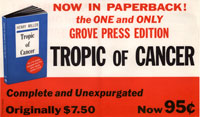

He used his share of the family riches defending works like Lady Chatterley's Lover, Naked Lunch and Tropic of Cancer against obscenity charges. In all three of these cases Grove Press was eventually vindicated, and these pioneering victories helped pave the way for the freedom of expression that exploded in the 60's.

Obscene, a new documentary about Barney, opens tonight at the Siskel for a week-long run. It was co-directed by Dan O'Connor and Neil Ortenberg, two former editors of Thunder's Mouth Press. We had the chance to speak with Ortenberg about how he got into filmmaking, Barney's legacy ... and why they didn't shoot the film in Thailand.

Chicagoist: How did you go about making the move from publishing to filmmaking? What made you take that leap?

Neil Ortenberg: I'd always wanted to make a film. I had been in publishing for close to 27 years, something like that. I don't want to date myself too much because I consider myself, you know, in my late twenties. [laughs] I published in that time--I published all kinds [of books], every genre, every category. But I had also published a number of film-related books, had made friends with a number of film directors. And some of the books we'd published had been turned into movies. It was always something I had wanted to do. And it just seemed like the time was right. I had wanted to do two things. One was publish this book, The Outlaw Bible of American Literature, which took me about half a year to do after I left publishing. And I did it with Barney. I had talked with Barney about doing a film with him for years. His idea of the film that we would make is that we would fly him to Thailand, and stage--it was kind of like a Captain Kirk thing. He wanted to go out in the jungle somewhere and stage Eleuthéria, the Samuel Beckett play. And then he wanted me to film that. And in addition to that he wanted me to bring in a bunch of cronies and give them cameras and have them run around Thailand in a kind of gonzo way. So it took me awhile to disabuse him of that, to let it sink in that this wasn't a film--it might be a film I'd enjoy if Warren Buffett was supplying us with money and booze, but I finally got him to understand that I just wanted to do a documentary. I thought he had a great story and I wanted to do a documentary. I wanted to tell his story. And we went back and forth. He wanted to do that Thailand thing because it's one of his favorite places. He just loves Thailand. But I finally I got him to agree that we wouldn't do that. At least this time.

C: Were there certain films or filmmakers that you had in mind as models for the kind of film you wanted to make?

NO: I did. Like My Best Fiend, the Herzog film with Klaus Kinski. The Kid Stays in the Picture was somehow in my mind. Also, The Fog of War. There were just different films that I thought might be somewhat of a template or partially a template. But I knew that with Barney, whatever ideas I might have about what would happen--I knew that it would be kind of anarchy as far as what would turn out. In many ways that is what happened.

C: It seems as if once you got Barney on board he was pretty eager to talk. But how about his friends and colleagues? Were they more hesitant?

NO: You know, it's funny. You watch the film and you make assumptions. There were many times that he didn't want to talk at all. There were times he didn't want to talk because he had ideas about how the film should unfold. He didn't want me to talk to certain people at certain times, and then that would change. It was very much of a roller coaster ride with him. Even though I've been his friend for like twenty years and our careers have intersected so many times, and I knew Barney so well on a personal level, it was still a roller coaster ride. He was fairly difficult. And in some ways I found he was shy. I mean I had spent hundreds of hours with him at his apartment over drinks late at night listening to him tell stories about his life. But once he was aware that the camera was rolling he became very self-conscious at times, which surprised me. He would clam up. There were times when we'd have an interview set up and he'd just sulk and go into the bedroom with his rum & Coke. So that was hit or miss at times. And also I realized that once the film unfolded, I felt so close to him as a friend and as a publishing colleague that I had really forgotten how much he loved film and considered himself a filmmaker. He had distributed films. He had produced a documentary. All of those things kind of weighed in the background of my mind as I set out to do the film. The other thing about filming him was that he really wanted to be a kind of co-director. Initially I just thought, oh, that's Barney being crazy, that's a nutty kind of thing. It was just a control freak thing. And then I realized that he just loves film, and here I was making a film about him. Barney knows no boundaries. So even though it seemed crazy to me, him being a co-director of his own documentary probably seemed completely reasonable to him. That caused a certain amount of confusion. Anyhow. The people we interviewed, there were no hard feelings. The biggest problem we encountered was--all the reviews so far have characterized the film more or less as a love letter to Barney. I didn't want it to be. I wanted it to show Barney as this kind of tragic hero but with all of the darkness and the demons that haunt him. I wanted to show that, but I don't think maybe we showed some of that. Or maybe he was so charming that--

C: He's really charming. I think it comes down to the fact he's this really major figure in 20th century publishing who's sort of been hiding in plain sight all these years that so many people just don't know about.

C: He's really charming. I think it comes down to the fact he's this really major figure in 20th century publishing who's sort of been hiding in plain sight all these years that so many people just don't know about.

NO: That was the other thing. We felt that he was so important, we wanted to tell his story, and bring him out of obscurity to whatever degree I could. I knew that the heroic dimension of what he had done really had to be highlighted. Which meant that I really couldn't do as much of My Best Fiend as I had intended. [laughs] I think it would have been a darker film and maybe less rewarding for some people. But I guess what I was going to say--the people we interviewed, you could tell that if I had injected them with Sodium Pentathol there would have been a lot of things they would have said that would have been more critical and more real. More revealing and more shocking. But also there was this kind of adulation and reverence for an icon that existed among almost everyone we talked to, and that came out on film. So there were very willing and happy to participate. There were thrilled. But in some ways it was a chorus of cheerleading. And rightly so--Barney had a tremendous impact on these people and was very generous. But again, the darker things, people didn't want to get into that. And I can understand that. So the film just ended up being what it was, and it came together in the editing. The four of us who worked on it all had different ideas, but we came together and at the end of the day I think we were all happy with it. Beyond the historical, political, cultural storytelling of the times and of Barney changing the culture we also wanted it to have an emotional impact on people. I'm hoping we succeeded. I think we did to some degree.

C: Barney's outsiderish, pioneering spirit is something I've been thinking about since seeing the movie. I've been asking myself if his efforts helped to pave the way for the freedom of information that's embodied in the internet, or if the internet was just another way that evolved of solving the problem of censorship. What do you think about that?

NO: I think it's probably both. I think Barney did change the culture, like Jason Epstein talks about in the film. He broke down barriers that led to all kinds of things that we take for granted now. But obviously there have been many forces that have evolved on their own that have reinforced the things that Barney did. I don't know if that answers your question. You know, Barney is still publishing Evergreen Review online. Even at the age of 85, with whatever money he has he's always trying to buy the latest technological gadget. His curiosity about technology is amazing, which is very unusual I've found for people who are of that age. He was friends with the president of Sony many, many years ago and somehow they gave him one of the first Sony moving picture cameras. I think he still has it. Even the thing I told you about earlier where he wanted to go out to Thailand and give six or seven cameras to different people--they actually did a film like that in Iraq [The War Tapes]. They gave cameras to a bunch of soldiers in Iraq. So Barney would have loved to have been in his prime now as technology is exploding. He'd be at the forefront, he'd just be going wild with that.

C: Do you think he would have had his own website and been a blogger instead of publishing?

NO: No, I think he would have been doing everything! [laughs]