Interview: The Onion's Nathan Rabin

By Rob Christopher in Arts & Entertainment on Jul 6, 2009 5:20PM

One of our very favorite pop culturists, for more than a decade Nathan Rabin has been head writer for The Onion A.V. Club. He's equally at home writing about Epic Movie or western swing, and you don't want to be on the receiving end of his wicked sarcasm when it's time to mete out a takedown.

One of our very favorite pop culturists, for more than a decade Nathan Rabin has been head writer for The Onion A.V. Club. He's equally at home writing about Epic Movie or western swing, and you don't want to be on the receiving end of his wicked sarcasm when it's time to mete out a takedown.

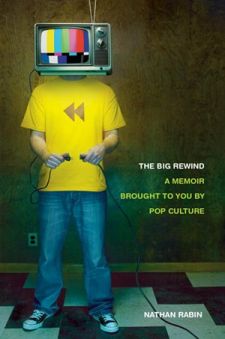

His new book, The Big Rewind, is so damn good that Roger Ebert himself recommends it, summing it up better than we can: "This hilarious, sad, truthful memoir is compulsively readable--a page-turning soap opera about a child abandoned by his mother, loved by his wise, thrice-divorced, painfully crippled, often unemployed father, shuttled through foster homes and asylums, and yet with an invincible sense of humor that led him to win a job on the original Onion in Madison ... he chronicles his adventures with a cross between utter shamelessness and painful honesty, and he is very funny."

We sat down with Nathan recently at Trader Vic's over a few Mai Tais and talked about growing up Jewish, working at Blockbuster, his short-lived stint as a TV show film critic and how the internet has scrambled geography.

Chicagoist: First off, how did you get a blurb from Roger Ebert?

Nathan Rabin: I callously exploited the fact that since we're both members of the Chicago Film Critics Association I had his email address and a few personal connections to him. Me and my frightening gestures and seizure-like facial contortions were featured fairly prominently on the Beyond The Valley of the Dolls DVD and the main producer I worked with on Movie Club used to produce Sneak Previews. Oh, and the last chapter of my book is about my failed audition to be a guest critic on Ebert & Roeper. So there was a fair amount of common ground. I lucked out in that Ebert is ridiculously generous with his time and energy and obscenely approachable. It seems like the more famous a person is, the more people you have to get through to reach them, but Ebert has managed to become a household name while retaining a common touch. Sometimes a blurb is written by someone who doesn't appear to have read what they're praising in comically hyperbolic terms but Ebert summarized the entire book in his blurb. I haven't done a word count but I think his blurb might actually be longer than the book itself. After I got his blurb I floated to work. I was elated. It was such incredible validation from someone I've always respected.

C: You're 33. Why are you writing a memoir?

NR: I had a television show called Movie Club with John Ridley, and it was this surreal, exhilarating and insane experience for me that I soon learned nobody in the universe gave a mad ass fuck about. There's no support group for people who've had their shows canceled before their time. I had forgotten one of the immutable laws of the universe: You, Nathan Rabin, Ain't Shit. I always get into trouble when I forget that. I was on AMC pretty much during their nadir. Long gone were the days when George Clooney's avuncular dad would come on and tell you a nice story about the movie you were about to see. They apparently weren't making any money taking the high road. So they started chopping the shit out of their movies and showing absolute crap. And the ratings skyrocketed. There was a point in the show where [John] Ridley said, "We had such a great show today and AMC is so appreciative that they've agreed not to run Missing in Action IV: Braddock for at least the next week." That line never made it onto the air and I'm pretty sure they ran Missing In Action IV: Braddock the following day. After Movie Club was canceled after fifteen episodes I needed an outlet for dealing with my violently mixed feelings about it that didn't involve binge drinking or a shooting spree. I'd been writing for The A.V Club for almost ten years and as much as I love my job, I felt I desperately needed a challenge. I needed to do something new. I wanted to do something that scared the shit out of me, that I didn't necessarily even know I was capable of. I guess I also felt like writing a book about my TV experiences would somehow give them value and meaning. I knew that the world didn't care that Movie Club existed, but I wanted to show what an intense, tragicomic experience it had been for a smattering of very colorful people. So I wrote that in about nine months and it felt really fucking great. It felt really different; I had never really written in the first person. At The Onion it's all in the third person, that's sort of drilled into us.

C: Here at Chicagoist we have to write in the first person plural, and it sort of forces you to be really creative.

NR: Or really snarky. And I say that as someone who makes his living writing for a newspaper that's arguably an original progenitor of snark. Once I started writing about my life the floodgates opened. It all came out. I didn't talk to anybody about it. Nobody cared about the show, so I figured no one was going to care about a book about the show. I wrote this book in part to prove, to myself as much as anyone else, that I was capable of writing a book. So I wrote what I hoped would someday be a book and I sent it to my agent. My first idea was incredibly fucking ridiculous. I was going to write three books: a book about my adolescence, a book about Movie Club, and a book about everything after. It was like a thousand fucking pages at one point.

C: So it was your Proust.

NR: It was, it was. It was fucking ridiculous. But you have to overreach. So I wrote this book and my agent read it and said, "Oh, this is great, this is like The Devil's Candy but for television. Let's send it to publishers and see what happens." I guess there were about twenty in the first tier. And literally about five days later he said, "Yeah, your book is basically dead. But it's an encouraging sign that they read this book so fast. Some people really loved your voice, loved your humor and your sensibility but felt the subject matter was a deal breaker. Nobody wants to spend $25 to read about a TV show nobody knows exists. Some of the people I sent it to, they just don't like you." My agent had the good sense to see the death of my manuscript as what the Chinese call a crisistunity. He asked me to write a proposal for what would become The Big Rewind, a memoir that would filter my life through pop culture. I went through a period of mourning. I'd written this book. It was dead. So I moped around for a week and a half then stopped feeling sorry for myself and decided to write the proposal. It was really long, like 110 pages, so it was a mini version of the book. He sent it off again and this time about five or six editors were interested. I'm horribly narcissistic, unlike every other writer in the world, so although the new book involved reliving pretty much every childhood trauma it was really exciting delving back into my back pages.

C: There's a lot of profanity. One of the things I like about your writing is that it has this vulgarity but an appreciation for high culture as well. Why do you think you turned out the way you did?

NR: A lot of it can be traced back to my dad. He's very smart and very funny. He graduated from The University of Chicago but he also has this very weird, very warped sense of humor. As a kid, one of his running jokes involved telling me to hide whenever we heard sirens because the police were coming to get me. Thanks, dad. As kid, I used to share a bunk bed with my older sister and dad would come in at night and tell us bedtime stories. He told us one story about this magical flying bunk bed and my sister, being an incorrigible smartass, said, "I hope that I'm on the top bunk when we go flying because Nathan still pees the bed." Being Jewish, I grew up in this culture that valued education and learning and history. And being able to swear creatively and proficiently. Lenny Bruce was Jewish. David Mamet is Jewish. Yiddish is a wonderfully obscene, confrontational tongue. Jews historically have had to be smarter than everyone else just to survive. My older sister would get very excited about ideas. She is a person of fierce convictions. I looked up to her, because she was always a straight-A student, Phi Beta Kappa, which my dad never gets tired of talking about. I was always the fuck-up. She infected me with all these ideas. I became a Feminist and a Socialist by osmosis before I really understood what either was all about. I developed a very active fantasy life. It was a way of distancing myself from what I was going through. When I was 14 I had a fantastic social worker who enrolled me in a course on gender roles in film noir at Facets. It was a revelatory experience. It was a totally new way of seeing the world. Every movie I saw was so much more exciting than my life. I felt, "Wow, this is where I want to be." It synced up perfectly with what I'd gone through. The world of film noir felt so foreign and so intimate at the same time. Of course the world is insane. Of course everyone is fucked.

C: About the same time as you I also worked at Blockbuster. And that totally exploded my view of movies. You could take home anything you wanted.

NR: Yeah, but they fucking kill you with the late fees.

C: It was like a free film school.

NR: Totally. As a painfully insecure sixteen year-old I thought the only way I could trick people into thinking I wasn't t completely worthless would be by being smarter and funnier and knowing more about movies than anyone else. It's amazing how much authority people give a sixteen year-old virgin because he's wearing a blue oxford shirt and khaki pants and standing behind a counter at Blockbuster. People were treating me like an expert in film because my after school job was at a video store instead of, say, a yogurt stand. It amazed me that someone with a master's degree would ask me what I thought of, say, the new Woody Allen video. I thought, "I masturbate fifty times a day. I live in a group home. I just failed freshman choir. I am not an expert on anything." At 21 I went from being the world's most overqualified video store clerk to being the world's least qualified film critic.

C: I recently read this fascinating book called Inherent Vice, and it's about the bootlegging aesthetic of VHS. And how that's been lost in the transition to DVD. Because DVD and streaming video have all these technological safeguards built in to prevent that from happening. Prevents you from making dubs, from passing a copy to your friends easily. Our generation grew up absorbing motion pictures by going to the movies, and watching them on TV and VHS. Now, it's completely different. You don't have the VHS component. It's DVD, and streaming video, and that's a bunch of clips taken completely out of context when you watch them. And cable TV with hundreds of channels. How do you think that's going to affect today's movie viewers?

NR: Oh, but I remember the "old days," when you had to walk to school sixteen miles each way and if you wanted to research something you had to go to the library and figure out the Dewey Decimal System. Today, everything seems so easy with the kids and their YouTube with the crazy rock & roll music and Netflix and whatnot.

C: It's a broad kind of knowledge, but it's shallow.

NR: Everyone's an insider. You don't have to be Peter Bogdanovich and interview Hitchcock and Welles and Ford to learn how they made films. Now you can just watch an audio commentary. You go online and there's information everywhere. I had to learn the hard way. Think of this way: VHS is a horrible medium. It breaks all the time. It doesn't make movies look the way the creators intended. But it was all we had. The culture of cinephilia is completely different. Geography doesn't matter anymore in a virtual world. A middle-aged academic in California and a teen in Vermont can bond over their love of Godard without ever meeting. I fear sometimes that the day of getting most, or all, of your information about film from a teenaged compulsive masturbator who just happens to work at a video may be behind us.