Barry Gifford's Long Road With Sailor & Lula

By Rob Christopher in Arts & Entertainment on Apr 26, 2010 6:20PM

Barry Gifford was born in 1946 in Chicago's Seneca Hotel, which is still there, nestled in the shadows of the Hancock Building. After a childhood spent largely in Chicago and New Orleans, and a short stint pursuing a possible career in baseball, Gifford focused his energies on writing. And he's never stopped. He's published in excess of forty books ranging from poetry, plays, essays (he even took a stab at the Cubs), screenplays, and fiction.

Barry Gifford was born in 1946 in Chicago's Seneca Hotel, which is still there, nestled in the shadows of the Hancock Building. After a childhood spent largely in Chicago and New Orleans, and a short stint pursuing a possible career in baseball, Gifford focused his energies on writing. And he's never stopped. He's published in excess of forty books ranging from poetry, plays, essays (he even took a stab at the Cubs), screenplays, and fiction.

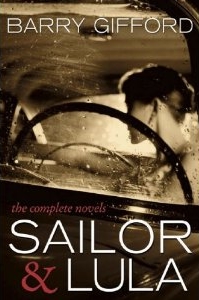

His newest is Sailor & Lula: The Complete Novels, collecting all seven books of the Southern gothic noir cycle that began with Wild at Heart. That first novel was a surprise hit, and caught the eye of David Lynch. In his movie adaptation, Lynch cast Nicolas Cage and Laura Dern as the book's protagonists, Sailor and Lula. They're two young lovers on the run from the law and Lula's headstrong mama Marietta.

But Gifford knew there was more to their story. Though we first encounter them as hot-blooded teens, over the next six books Gifford observes them growing up, mellowing out, and adjusting to parenthood. The final installment, The Imagination of the Heart, sees the characters grapple with old age and their impending mortality, framed by a post-Katrina New Orleans setting.

Gifford talked to us about the evolution of Sailor and Lula, working with David Lynch, his kinship with Flannery O'Connor, and how Chicago's hot dogs compare to New Orleans' crawfish etouffee.

Chicagoist: First of all, what was it like to see all of your novels in the same place, in the same book together?

Barry Gifford: Well, somebody called it a milestone when they saw it. And I said, "It's either that, or a headstone." It's the way I always wanted it, because really it's all one long novel. In fact, when I had sold Wild at Heart to Grove Press--you know, they were preparing to publish it. But immediately thereafter I wrote Perdita Durango, and I realized that there were going to be more. And then I got the idea for Sailor's Holiday, which was going to be the following novel. I said to my editor at the time, "You know, I think we ought to hold up on this and wait because there's going to be more." I mean, I didn't realize there were going to be seven novels/novellas all told. But he said, "No, we can't do it, because David Lynch just made the film of Wild at Heart." They wanted to bring the paperback out when the movie came out. So I said, "Okay," and they went ahead and they did Wild at Heart. But I always had it in my mind to put it all together. That's really the form I always envisioned it being in, so finally it's done. I'm really happy.

Chicagoist: So you knew from the beginning that that there would be more than just one book?

BG: When Perdita Durango first came into being, in the opening part of Wild at Heart, I realized that Perdita was a very strong character and she was threatening to take over the book. So what I really did was de-emphasize her in my own mind. I allowed her into Wild at Heart, but the character was so fascinating to me and I realized that she deserved her own book. And that became the second one. It came pretty fast, as far as that goes. In fact, when Lynch had written the first screenplay it was exactly like the book. The ending was the same and all that sort of thing. And then there was some debate about putting a happy ending on Wild at Heart. He called me up and said, "What happens? Do Sailor and Lula get back together again?" I said, "Definitely." In any case, I was very aware that there was more to come, that Sailor and Lula had a future.

Chicagoist: That must have been an incredible gift, to realize that there was so much more to dig into.

BG: Well, more than one reviewer I know has mentioned that these kinds of characters, if a writer's lucky, these characters only come along once in a lifetime. As long as they were alive and were speaking to each other, if not to me, I was just going to go with them. That's why it was a nice surprise to me that after fifteen years The Imagination of the Heart came about. Lula got the last word, which is the way it should have been.

Chicagoist: Getting back to the movie a little bit, although he did follow your book very closely, obviously Lynch kind of gave his own spin to the story. After you saw the film do you think that influenced the direction the subsequent books took?

BG: No. The only thing that entered into it is, there are a couple places where there is a direct reference to the movie. Later on, I think it's in Bad Day for the Leopard Man, toward the end where I even talk about doing a film called Wild at Heart, and there's a little play on Lynch and all of it. But I mean, these characters were well-formed, they were established, they took on their own identities.

Chicagoist: I saw the movie before I read the book. And I saw the film and I thought, oh well, all this weird stuff, that's obviously Lynch doing his own spin on it. And then I read the book and it was all in there!

BG: Of course he added stuff. He added the scene where Sherilyn Fenn is the girl who's been in the car wreck. The guy in the wheelchair yelling stuff. But basically the thing is, David, as he's said many times, was inspired by these characters and the setting and the whole situation, and so of course he was going to add his touch to it. The things that were inspired in him, and all that kind of thing. And so that was all fine. But it didn't affect the writing of it. That was all established.

Chicagoist: I'm so glad that you let Johnny Farragut live a natural life through the end of the books, instead of killing him off in some bizarre way, like so many of the other characters.

BG: Oh yeah. No, no. I mean, the people who get killed off are basically--they're pretty random for the most part. That's why I say that it's one long novel. Here it begins with Beany and Lula, just before Sailor gets out of prison. And it ends with Beany and Lula.

Chicagoist: Speaking of death, to me that's where the suspense comes in, reading the books. You know, is this character going to live or die? And how are they going to die? Why are the deaths so random?

BG: Because that's how life appeared to me. And I've got news for you, as I get older this is even more true. People die, or they get killed, or something happens. And I wanted to express that randomness about life. It's very nice to make plans for tomorrow, but you don't really know if tomorrow's going to come. I guess if there was a message it was, live your life as best you can while you have it to live. But I wasn't consciously trying to send a message. It's just that that's how life and death have always appeared to me.

Chicagoist: But at the same time, the way the characters isn't die isn't just some average, run of the mill heart attack. In most cases it's some bizarre incident.

BG: Well, the style of the book, if you will--it's written as a kind of violent satire. And so you have to get the humor, and realize that it's satirical. All through these books I was dealing with the difficulties and the problems in the world as I saw them. Whether it's fundamentalism or racism or so forth. These are all through the books. And if there's anything that I'm saying about these things--my theme is anti-violent. This is all so bizarre, as you say, and the world does seem that way to me and has seemed that way to me for a very long time. It's gotten even more bizarre, if anything. I couldn't possibly have matched reality, the truly crazy things that happened and continue to happen. The idea was that Sailor and Lula were a kind of filter. They're pure products. The poem "To Elsie," by William Carlos Williams, it's a wonderful poem that begins, "The pure products of America/go crazy--," and I always had that line in mind. What I wanted Sailor and Lula to represent were innocents. That they were perhaps naive, but innocents nevertheless. And here was all this shit raining down around them. They couldn't always avoid it. But at the heart of it was their love story, which was evident, and the fact that they remained true to one another to the end of their lives. It's a picaresque. They're just going down the road, just like Don Quixote and Sancho Panza.

Chicagoist: The details like place names and character names and the music that's playing, you're almost obsessively detailed about those.

BG: Well, that's my soundtrack that I supply. I'm establishing the milieu. But Sailor and Lula, they're always the same. They really are. Lula is the mature one. She's the one who more obviously matures. Sailor is usually a lunkhead--and early on he gets dragged into things and sets himself up for things. It's Lula who is the strong character and the one who survives after all. In my experience, women have a much more intelligent approach to problems, and are stronger than men. And in fact I learned more in some ways from female writers than I did from men. Or from gay writers. E. M. Forster, say. People from whom I took a certain kind of wisdom and understanding and patience were generally female, or homosexual, or both.

Chicagoist: What female writers have you admired? Just to narrow it down to one person, would you say that Flannery O'Connor would be on that list?

BG: You know, here's a funny thing about Flannery O'Connor. I'd written some of the novels and a friend of mine, in Chicago, said to me, "You know, you have a lot in common with Flannery O'Connor." And then there was a review of one of the books--I think it was even in the Chicago Tribune, if I'm correct--making a joke at the beginning, saying that Barry Gifford is the product of perhaps one night, maybe Flannery O'Connor and Jim Thompson came together and their progeny was Barry Gifford. It was sort of a cute remark. But I had never read Flannery O'Connor. It was a lacuna in my reading history. Paul Auster gave me that 3 by Flannery O'Connor book. That's when I first read Flannery O'Connor. So it was actually really late that I came to her. And I loved her work. I absolutely adore her work. I see her as a sort of Southern cousin.

Chicagoist: It must come from that sort of Southern atmosphere--

BG: Oh absolutely it did. Well, when I began writing Wild at Heart, I had a made a conscious recognition, let's put it this way, to write out of that Southern side of myself rather than the Northern side. Because I had both. But I hadn't really written out of that Southern side. I had written a novel, Port Tropique, which took place in a Central American country and it ended in New Orleans. But I had never really written from that side of myself. That's what began with Wild at Heart.

Chicagoist: One of the things that's so prevalent in the Southern side of your writing is the atmosphere of religion, religion being everywhere.

BG: Oh, absolutely. The people are obsessed. As a child I remember constantly being sort of assaulted by it in a way. The fundamentalists, particularly all the Southern Baptists. And all the churches. And then the black churches too. All of it, it all interested me. You know, what are these people going on about?

Chicagoist: But you yourself were not really raised religiously, were you?

BG: No, I was not. My father was Jewish, but not a practicing Jew, and my mother was raised Catholic. Although my grandmother, her mother, was very close, very much involved with the Catholic church. My mother went to Catholic boarding school and all that sort of stuff. But certainly I was not raised in a churchgoing mode. Nobody ever talked about religion to me one bit. On either side. So it was just left up to me to make my own determination of what was acceptable and what wasn't. And when I started reading the Bible, I just saw it for what was it was; which, as I've written, is the greatest noir novel of all time. And I stick by that. I'm talking about the King James Bible.

Chicagoist: What was it like for you, watching coverage of Hurricane Katrina?

BG: Like everybody else, it was horrifying. It was like a nuclear holocaust. I've been there twice since Katrina, and I'll be there again in May. So I was horrified just like everybody else. But you know, it's sort of like when they used to talk about the San Francisco earthquake. Well, in San Francisco they always called it the Great Fire. Of course it was an earthquake but everybody always talked about it as a fire. One of the reasons was, the people who owned the property, they didn't want to dissuade people from coming out here, to settle here and build and rebuild in San Francisco. "Earthquake" was a much more frightening term, because that was something that you couldn't control. But a fire could be controlled. You can build better, build differently, use different materials, and so forth and so on. Now, Katrina was the flood. And the flood was man-made. It was because of the deficiencies in the levees. The thing is that when the barriers failed--they would have survived the hurricane. They did survive the hurricane. That wasn't what did it. The levees failed. They were insufficiently constructed, there were holes in them, and whatnot. So in my way of thinking about it, it's the Great Flood. That's what destroyed much of New Orleans. And then of course the concurrent events with Bush's ineptitude and how they couldn't handle the situation or get food and water to the people--the whole thing was just horrifying. And unfortunately so much of the New Orleans that I loved is gone, and permanently so.

Chicagoist: So you think it's changed forever.

BG: It's changed. So many of the people are gone. All the neighborhoods, the Lower and Upper Ninth Wards, and Seventh Ward--there's nothing there. There's no place for the people to live, so they had to move on to Houston or Chicago or California or wherever, to re-establish and remake their lives. So much of that, those people and those places that made New Orleans rich for me--so much of that is gone. It's just flat-out gone.

Chicagoist: If you were to summarize New Orleans as a plate of food, how would you summarize it? Or, let me put it this way, what sort of dishes do you remember eating, growing up?

BG: Dishes. That's an interesting question. As a kid I always loved eating oysters and shellfish, mostly. But then I developed an allergy to shellfish in my forties, so I can't eat it anymore! It's one of the most terrible, terrible things. But in fact my very favorite dish was always crawfish etouffee. That was always my favorite.

Chicagoist: And how about Chicago? What were the dishes you most liked, growing up? Was it the proverbial hot dog, or was it something else?

BG: That's a tough question. I could answer it more for other people than for myself. I can't imagine my old friend Magic Frank doing anything other than eating two Italian beef sandwiches before school every morning. That, and Vienna hot dogs, those used to be associated with Chicago. But now Chicago's changed so much--now it's really gourmet central. There are really excellent restaurants in Chicago. But as a kid growing up, what are you eating? You're eating cheeseburgers and hot dogs and pizza just like every other kid everywhere else.

Chicagoist: You've talked a lot about the Northern side of your writing and the Southern side. Those seem to be the two sides of your writing.

BG: Somebody said to me years ago, he said, "What it is you're really doing is you're writing history. You're writing your own version of history." So, for instance, the one that's coming out in September, Sad Stories of the Death of Kings, I wrote that to really kind of preserve the language and the history of that time and place. Because it doesn't exist any longer. It's gone. It's gone except for in my mind, and I want to preserve it. That's always been a very conscious motive as far as I'm concerned. Writing about the Chicago of the 50's and early 60's, that's one place. And then the Deep South. But in the South, I write about the contemporary South as well. And that's probably because I chose to spend so much of my adult life there as well. I kept the place in New Orleans for eight years in the 90's and would always go back there. I would be down around the Florida Keys and around there all through the 70's and 80's. So I still kept a connection. But Chicago I had left when I was 17. I really didn't have people there any more. I really didn't have the same kind of connection. My connection to Chicago basically goes back to the 50's, late 40's, very early 60's. That's the Chicago I know about and that's the Chicago I can write about.