Review: Beethoven Festival's Symphonies No. 2 & 3

By Alexander Hough in Arts & Entertainment on Jun 9, 2010 7:30PM

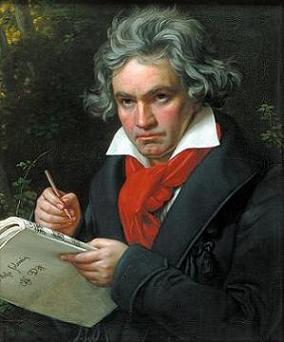

Portrait of Beethoven by Joseph Karl Stieler

These symphonies mark the beginning of Beethoven's so-called Middle period. In 1802, a doctor sent Beethoven to Heiligenstadt, a village outside of Vienna, in the hope that a removal from urban life would reverse his deafness. During these dark days, grappling with his ironic fate nearly drove Beethoven to suicide, thoughts documented in the Heiligenstadt Testament, an unsent letter addressed to his brothers Carl and Johann that was posthumously published in 1827.

This makes his Second and Third Symphonies, the former composed while in Heiligenstadt, the latter the following year, so baffling. The Second is relentlessly happy, even straying into goofy territory in the last movement, with barely any time spent in minor keys. The one notable exception is the short phrase in the first movement's Adagio introduction that portends the opening of the Ninth Symphony, down to the key (both are in D minor), a piece of far greater gravity and introspection. In a subtle but brilliant move in last night's performance, Haitink pulled the tempo back ever so slightly following this passage. This hiccup barely registered before the music regained its footing and disappeared into the merriment of the Allegro con brio. As with last week's Eighth Symphony, the CSO achieved a pristine Beethovian sound on this more Classical work, and Haitink allowed the orchestra to plow through the rollicking piece, conducting a faster than usual tempo for the Larghetto - a choice that felt surprisingly right - while holding things in control for the scherzo and finale.

The Third Symphony is a more confusing case. Much is made of the piece's dedication. Beethoven originally meant the symphony to be an homage to Napoleon Bonaparte, but scrapped the plan when Napoleon declared himself emperor in 1804. Beethoven instead opted to title the work "Sinfonia Eroica" ("heroic symphony"). Eroica is undoubtedly a different animal than Western music written prior, both in the technical aspects of the work - it was substantially longer, more difficult to perform, and more elaborate harmonically - and in the extramusical subject matter. But again, superficially, this piece is still removed from the central crisis in Beethoven's life. This, at least, was the reading Haitink and the CSO gave. In light of the Heiligenstadt Testament's admissions of sorrow and the subsequent spate of prolific composition, it's hard to see this symphony, ostensibly about a hero prevailing in the face of adversity, as something other than a personal document. In the Heiligenstadt Testament, Beethoven says almost as much. In addressing his possible suicide, he said, "It seemed to me impossible to leave the world until I had produced all that I felt was within me."

With this in mind, it's hard not to hear tragic desolation in the second movement funeral march, although instead of drawing out the pathos to further elevate the symphony's ultimate triumph, Haitink took the Adagio assai at a rapid speed. The brisk tempo falls in line with the Beethoven Festival performances so far - broadly, fast slow movements and moderate fast movements - and although the attention to the whole cycle is appreciated, and although it makes sense on the micro-level since at Haitink's tempo was one you could actually march to, speeding up the second movement lightens its emotional heft. (For an example of the difference tempo makes, check out a slow version of the funeral march's heartbreaking fugue, and then check out a faster version of the same music, neither of which is a fast as Haitink's version). In any case, it was beautifully performed, particularly the opening, with the rich, clear tone of the cellos and basses anchoring the music.

There are two ways to infer what Haitink was thinking with his second movement pacing: either he sees Eroica as an emotionally simple piece more like the Second, or an overly dramatic interpretation isn't needed to express the music properly. If the first movement, with its relatively straightforward yet boisterous reading, provided an ambiguous answer to this question, the edge-of-the-seat excitement in the final two movements erased any doubt. The scherzo bounded forward solidly even when the rhythm bounced around, the orchestra playing with a jaw-dropping combination of wildness and clarity (special credit should be given to the horn trio, which we wished came around more than twice). The symphony ended with a performance of the finale as brisk as the funeral march but which we felt fit the exuberant, playful theme and variations, especially in the middle Andante section that too often becomes plodding and boring. The CSO's performance was brilliant throughout, with standout performances from the woodwinds, particularly principal flute Mathieu Dufour and principal oboe Eugene Izotov.

We're all in on this Beethoven Festival now, and we urge you to be, too. Remaining performances include the Fourth and Sixth Symphonies (this Thursday and Friday), the First and Seventh Symphonies (June 15-16), and the Ninth Symphony (June 18-20). There are also free chamber music performances before each CSO concert, a piano recital this Sunday, and symposia on the next two Saturdays.