The Beethoven Festival: A Slightly Premature Retrospective

By Alexander Hough in Arts & Entertainment on Jun 16, 2010 7:00PM

Portrait of Beethoven by Joseph Karl Stieler

Running through a cycle like the Beethoven symphonies in a concentrated amount of time isn't just a fun exercise (enjoyable as the individual concerts have been); at its best, this sort of musical survey can prompt new insights into well-worn works. This is no small task, though, and the programming and sequencing of the concerts is as important as the performances themselves.

In constructing the programs, the CSO had to obey certain economic realities. Most important among these is that people are more likely to pay good money to see the "bigger" Beethoven symphonies, the Third, Fifth, Seventh, Ninth, and, for some, if not this author, the Sixth. To sell tickets to all the shows, those pieces have to be paired with Beethoven's lesser known symphonies. We're fine with that - short of completely debasing the music or embarrassing the musicians, if it puts butts in seats (even a disproportionately high number of wrinkly, old butts), then that's great.

But even within these constraints, the Beethoven Festival has been largely successful. Beethoven's symphonies were written in a short time span - he began work on the First in 1799 and finished the Eighth in 1812 - and while these works basically represent the entirety of Beethoven's Middle period, they were composed in three distinct bursts: 1799-1802 (First, Second, and Third), 1806-1808 (Fourth, most of the Fifth, and the Sixth), and 1811-1812 (Seventh and Eighth).

As mentioned above, certain symphonies are seen as bigger, both literally (size of orchestra, length, complexity of harmonic construction) and figuratively (thematic and emotional content). The curiosity of Beethoven's symphonic oeuvre is that these works sprung up amid apparently simpler symphonies. Two of the Beethoven Festival's programs examined this contradiction: last week's performances of the Second and the Third, and last weekend's concerts with the Fourth and the Sixth. These shows exposed cracks in the common distinction, although each pulled in a different direction.

The Third is seen a gargantuan piece of art that arose out of nowhere to change music, and to a certain extent, that's absolutely true. But heard on the same concert as the Second and with a relatively restrained performance - it was the first time we've heard the CSO and wished the brass was louder - the Third was placed in context, illustrating a more subtle creative transition.

The Fourth and Sixth concert was altogether different. Robert Schumann famously described the Fourth as "a slender Grecian maiden between two Nordic giants" - the Third and the Fifth - but boisterously performed and coupled with the contemporaneous Sixth, which received an equally energetic performance featuring as rich a string sound as we've heard all festival, it became clear that the Fifth is actually a Nordic giant between two voluptuous dimdl-wearing maidens. That the concert commented about a previously-performed symphony - the Fifth having been on the festival's first program - in addition to the Fourth and the Sixth is a testament to the programming acumen.

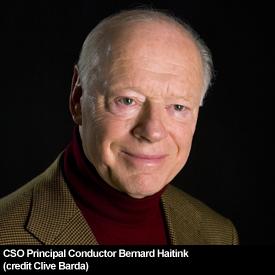

Bernard Haitink has four concerts left as the CSO's principal conductor

It's fitting, then, that the Seventh was Haitink and the CSO's most exciting, complete performance to date. Throughout the concert, the orchestra balanced barely-restrained enthusiasm with precision - the violins' bows audibly scratching during the first movement's furious dance, the timpani playing a bit too loud during the Vivace's first tutti section, the horns bellowing audibly anyway - all while transparently tracing individual lines and accurately maintaining the rhythmic ostinato that propels the first movement (to hear the difference, listen to the rhythm become a square, duple feel as often happens, and then listen to the same excerpt that keeps the lilting triple feel).

The Allegretto, the symphony's most popular movement from the get-go (an encore performance was demanded at the premiere, as well as at a subsequent performance a couple months later), was, like all the slow movements in the festival so far, taken briskly, although the tempo choice wasn't a hindrance like it was in the Third's funeral march. It was performed as a more personal article, only getting more intimate as the tempo broadened later in the movement. With the third movement, the symphony regained its dancing legs, although nothing, save for the up-tempo performance of the Third's final movement, prepared us for the finale, which was ripped off at a blistering pace. The music seemed barely in control; not from the perspective of what the orchestra could handle - last night they seem especially proficient - but rather the music itself was pushed to its breaking point, pouring a strangely pleasant tension into the sprint to the end.

The outlier among the festival's programs was actually the first concert, with the Fifth and Eighth Symphonies. The two symphonies contrasted - more so than other programs' works contrasted, including last night's performance of the First, which we assume is a consequence of Haitink and the CSO evolving and arriving at their Beethoven voice over the past two weeks - but there was no cohesion, or lack thereof, between the symphonies as a whole. That program might have just been a marriage of convenience between the two leftover symphonies. But, hey, it was a pretty sweet concert just the same, and although we said the Beethoven Festival wasn't just a fun exercise, that doesn't meant it's not a fun exercise. It's hard to argue against enjoying the concerts individually, or even purely aesthetically, after the four concerts we've seen.

You still have a chance to catch the Beethoven Festival, albeit a small one given the few tickets remaining. Tonight the CSO will reprise last night's performance of the First and Seventh Symphonies, and the Ninth, with its famous "Ode to Joy," will be performed Friday, Saturday, and Sunday. There's also a final symposium at noon on Saturday.