Beethoven Festival "Ode to Joy" Finale Powerfully Refined

By Alexander Hough in Arts & Entertainment on Jun 22, 2010 7:30PM

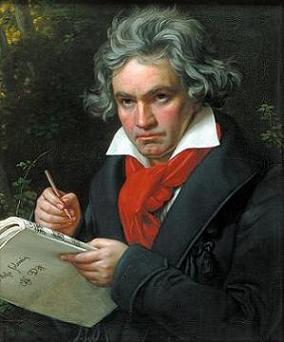

Portrait of Beethoven by Joseph Karl Stieler

For the first three programs, the festival's performances had been, on the whole, restrained. The readings were crisp and exciting, but largely through moderate tempos - fast slow movements, slightly slow fast movements, standard outer movements, minimal tempo changes within - Haitink kept the CSO out of the music's way, allowing the brilliant orchestra to shine within the frame that Beethoven provided. That held true until the wild performance of the Seventh, with it's rough-hewn first movement, the doleful Allegretto (easily the festival's most heartbreaking music), and the finale's white knuckle ride. It wasn't inappropriate or sloppy; it was just viscerally exciting in a way the previous performances hadn't been. With that concert fresh in our memory, and given the Ninth's singularity, all bets were off concerning what the final concert would be like.

Which is why the most notable aspect from the CSO's performance of the Ninth was how not out of the context of the festival as a whole it was. It of course makes sense in retrospect that Haitink, having spent the festival uniting the symphonies with straight-laced, rich interpretations, would opt for connection and consistency over extending the wild-eyed mania of the Seventh. There was no regression in the CSO's Ninth, either; tempos jibed with those from previous performances, and while there was no shortage of exhilarating moments, Haitink never lingered, allowing the music to keep moving forward in a sensible arc. The restraint benefited the music, most notably in the scherzo, the one whole movement that carried the Seventh's torch. The music is tempting to blaze through or to over-dramatize (just ask the producers of Keith Olbermann's show), but Haitink's version, like the Seventh's scherzo, was lively without being tense. While the strings didn't swipe their bows with the same violence they used in the Seventh, the unison sections were fired off like a machine gun, while still maintaining the chamber music-like clarity that's been the orchestra's best sonic feature throughout the festival.

Concertmaster Robert Chen (center) and bassist Stephen Lester (left) give Haitink the Theodore Thomas Medallion (Photo by Todd Rosenberg)

But it's there that we'll stop nitpicking. For the remainder of the "Ode to Joy" finale, a symphonic movement unlike any Beethoven had written in length (nearly a half hour), content (inclusion of vocalists), and form (almost a symphony unto itself), Haitink and the CSO shined as they had over the past three weeks: emotional but not overwrought; finely detailed, even among the four vocal soloists singing over the orchestra. The musical narrative, despite stretching over the length of Beethoven's longest symphonic movement and starting and stopping amid several ideas and sections, was as flowing and cogent as at any point in the festival, and the coda rivaled the performance of the Seventh in brazen, high-octane excitement. While we wouldn't have been shocked to hear a gutsy Ninth, the actual performance was a perfect final chapter to a refined, invigorating (if not revolutionary) cycle of Beethoven's symphonies.

The Ninth, and the Beethoven Festival, in general, was a nice way for Haitink to conclude his four-year span as principal conductor. He was greeted with adulation from the audience and, more significantly, the orchestra (an amusing custom, string players wag their bows back and forth, giving the group, already dressed in penguin suits, a particularly bird-like air). On top of that, the CSO gave Haitink the Theodore Thomas Medallion for Distinguished Service, an honor, named after the orchestra's founder, given to significant outgoing musicians. No need to get overly sentimental, though - Haitink returns in May and June 2011 to lead performances of Johannes Brahms's Fourth Symphony and Gustav Mahler's Ninth Symphony.

It's a time of transition for the CSO, too. After a week off, the group will retire to their summer home at Ravinia, and when they return to Symphony Center this fall, they'll be under the baton of new music director Riccardo Muti, the first time the CSO will have had a full-time leader since Daniel Barenboim's departure in 2006.

For reviews of previous performances from the CSO's Beethoven Festival, click here.