Doc Explores The Strange Powers Of Stephin Merritt

By Steven Pate in Arts & Entertainment on Jan 11, 2011 4:40PM

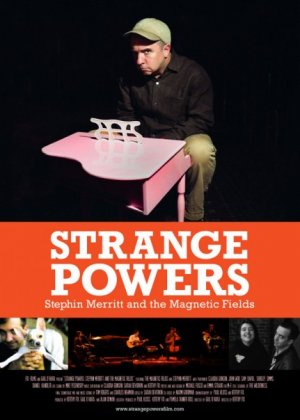

Pop songwriting virtuoso Stephin Merritt and his cult musical group the Magnetic Fields completed a pilgrimage from the music conservatory division of the indie rock avant garde in the early nineties to songwriting immortality with 1999’s monumental 69 Love Songs and never looked back. 2010 saw the release of their 10th record, a sold-out six-night stint at the Old Town School of Folk Music, and the premiere of a documentary about the group, Strange Powers: Stephin Merritt and the Magnetic Fields at SXSW. The film is an endearing portrait of the cerebral baritone who is often lazily labeled as simply prickly or aloof but is adored fiercely by his fans and guarded jealously by his friends and an ever-present chihuahua. We talked with co-director Kerthy Fix about this spending a decade making this documentary, about exploring the creative relationship between Meritt and his collaborator Claudia Gonson and about Meritt’s place in music history.

Pop songwriting virtuoso Stephin Merritt and his cult musical group the Magnetic Fields completed a pilgrimage from the music conservatory division of the indie rock avant garde in the early nineties to songwriting immortality with 1999’s monumental 69 Love Songs and never looked back. 2010 saw the release of their 10th record, a sold-out six-night stint at the Old Town School of Folk Music, and the premiere of a documentary about the group, Strange Powers: Stephin Merritt and the Magnetic Fields at SXSW. The film is an endearing portrait of the cerebral baritone who is often lazily labeled as simply prickly or aloof but is adored fiercely by his fans and guarded jealously by his friends and an ever-present chihuahua. We talked with co-director Kerthy Fix about this spending a decade making this documentary, about exploring the creative relationship between Meritt and his collaborator Claudia Gonson and about Meritt’s place in music history.

C: I’m really happy this Strange Powers is finally in Chicago.

Kerthy Fix: I know, we’ve had so many requests from Chicago that I’m sad it’s only two days (January 15th and 20th). But that’s all the theatrical agent could get. If it does well, maybe they’ll bring it back because we’ve had a ton of interest in Chicago.

C: Is your movie about introducing Stephin and the Magnetic Fields to more people? Or is it more for fanboys like me to watch?

KF: We wanted to satisfy the fans, obviously, but we’re making the case for Stephin’s songwriting. We feel like he’s part of the American standards. He should be recognized the way that Willie Nelson or Loretta Lynn or Bruce Springsteen are recognized, as a truly American voice in many different genres. But he’s representing a point of view that has this ironic distance that allows us to wallow in our emotions that we might have about our break-up or being in love, but every song always has this humorous twist that where you can stand outside and laugh at yourself and that point of view. I think that’s very of our time. I think in 100 years people will look back at Stephin’s songs and say that they really say something about people at a particular period of time.

C: Is Stephin consciously thinking about his place in music history?

KF: He’d have to address that. I think that he takes his work very seriously. He’s like Stephen Sondheim in that he probably loses sleep over a good line or a good melody. Just a really serious artist of the first order. I found over the years, as we were shooting, a tremendous admiration for the group-mind of Stephin and Claudia and the folks that are around them. In the 90s, Claudia had to drive them down the stream of indie rock. I don’t think that’s where Stephin sees himself situated comfortably, but where else do you place yourself if you’re a new wave kid in Cambridge in the nineties? You can’t really write for Broadway necessarily. Stephin says he wanted to create entire worlds, and in a song he can create that world with a character and point of view and a place. Like ‘Papa was a Rodeo’ really evokes a place and a personality.

C: There seems to be a good bit of footage of the actual creative process

KF: I had made a series with a filmmaker, Jennifer Fox, and her style of shooting is to shoot a lot, a focus on verite that really influenced me. When I started shooting seriously around 2003 they were recording “I” and we spent five days, just there all day shooting like ten tapes a day because once you enter an electronic instrument into a conversation with people, everybody gets self-conscious. So you kind of have to break that down by being around a lot and just by your very presence not interfering. I actually believe in a philosophy of compassionate observation, and that documentary does something positive for the people who are observed. I don’t want to put words in their mouths but i suspect that Stephin and Claudia were concerned that even though we came in as friends, that we might try and skewer them a bit. So they were really cautious, and they were really clear with us that the film had to focus on the work and not on their personal lives. So that kind of set up a clear boundary.

[Co-Director Gail O'Hara] and I were both so interested in the relationship between Stephin and Claudia, and found that an unusual creative relationship that we hadn’t really seen. You know, that fag hag/gay man-sibling-like-old married couple-long-time friend thing... you haven’t seen that model in pop music all mapped out. We thought that was an interesting relationship. And Claudia’s effusiveness, her outgoing nature, really brings this component to Stephin, who’s not so effusive. He’s working with the same people for twenty years, you know? You can’t be a jerk and do that. People care about him. So we felt like he had been misrepresented and Claudia hadn’t been understood fully for her role, so we wanted to map that out with verite footage. You shoot for a while, and that’s going to be come clear.

C: Sounds like the total time was about ten years. How did you know when you had enough?

KF: Oh god. [Laughing] We finally just wanted to go on with our lives. We weren’t shooting nonstop, but any time they had something going on we would go over. We kept waiting for something dramatic to happen in Stephin’s career. He’s really annoying in that he keeps just showing up and writing his music in a very mundane way. He’s not having drug overdoses or plastic surgery or anything crazy. But he does move to L.A. in the course of the film. Once he told everyone he was moving to L.A., that was a breakthrough. What’s going to happen? Claudia’s in Brooklyn. They talk on the phone constantly. They’re really enmeshed. We just tried to focus the film on how Stephin’s mind works, how he writes songs and also his relationship to Claudia. Claudia really becomes the heart of the film and you really care about her by the end of the film.

C: It’s not like Stephin or Claudia said “that’s enough guys.”

KF: Stephin has said in the Q and As that he didn’t even know we were making a film. [laughs] And we’re like “but when we were putting wireless mikes on you and the cameras are showing up” and he says “there are always cameras around and people putting mics on me.”

C: You talked about his workman-like nature, not being dramatic about his life and that being frustrating from a narrative perspective, but it does seem wrapped up in my idea of him and the group: that their personalities are effaced into the music itself. In a certain sense, this seems to be why Stephin is not talked about like Willie Nelson or Bruce Springsteen: because his personality is derived from the work and not sold alongside of it.

That’s really accurate, and Stephin is very firmly not interested in the creative project of persona in that pop space the way a Rufus Wainwright or a Lady Gaga would be.

C: It’s kind of refreshing sometimes

KF: I agree. Clear out some space for everybody. Why should people’s personal lives be the subject of all this attention? I’m as guilty as the next person of reading Jezebel and Gawker but I really appreciate Stephin adamantly not submitting to that because there’s a lot of pressure on him to do that.

C: I see a lot of interesting people in the credits of the film I assume talking about the Magnetic Fields. I imagine it’s not hard to get people who like this music to talk about it.

KF: Yeah we had good luck, with Peter Gabriel and Sarah Silverman and Neil Gaiman. Neil and Peter are both friends. Neil’s much closer, and they work together (Coraline being the most recent example). It’s funny though, I was amazed through the course of the film, you’d say to someone who’d seem like they would be a fan through their interests and just who they were, “I’m making a film about the Magnetic Fields,” and half the time people wouldn’t know who I was talking about. Of course if they did know, they’d be like “Oh my God! That’s so great!” People who are more literary appreciate him, but I also noticed we had a really good run with film festivals--more than any other film I’ve worked on, this film did great in the festival circuit--and i think it’s because an inordinate number of festival programmers are fans of the band, and they appreciate that kind of witty, literate, pop culture reference perspective.

C: I saw you just went to Chile, so it must be doing well abroad.

KF: We had sold out screenings there. There’s a really great film festival in Barcelona called In-Edit, sponsored by Beefeaters. They screened the film and were big fans, and they sort of franchised their festival to other spanish-speaking countries and also Berlin, and they’ve been taking it around. In Scandinavia we did Oslo and Sweden in November, the London Film Festival of course, and Karlovy Vary. It screened in Bosnia. It’s kind of incredible, there are fans everywhere.

C: And you’ve been working on a Le Tigre documentary, what’s going on with that?

KF: We had to work out some licensing issues but we finished that, actually I’m just now burning some DVDs, and delivering it to Oscilloscope, who’s releasing it, and it’s going to premiere at a major film festival in 2011. It’s called Who took the Bomp? Le Tigre on Tour. It will show iat the Chicago International Movies and Music Festival. And Strange Powers may screen again then as well.

Strange Powers screens at the Gene Siskel Film Center on January 15 (with a Q&A from the filmmaker) and January 20. Additionally, there is a Chicago preview and premiere gala at Berlin, 954 W. Belmont, on Thursday, January 13.