From the Vault of Art Shay: On Amateurs and Talent

By Staff in Arts & Entertainment on Feb 23, 2011 7:00PM

Five or six ardent amateur photographers, all friends, and I think, fans, of my pictures, have in recent months asked me if I ever met, competed/slept with, or really studied the fine photographs recently unearthed at a house sale by a young promoter, John Maloof. Mr. Maloof has invested in good prints of the late Virginia Maier's Rolleiflex negatives, and has made the rounds of the museums and even the gallery that sells my work, the Daiter Gallery. (Ed. Note: This would be as good a time as any to remind you of Chicagoist's coverage of Vivian Maier's photography. — CS.) My interrogators all point out that Ms. Maier "did street pictures, too." So, for maybe fifty years, Virginia and I were unwitting colleagues and never crossed paths.

There was another photographer in our class, still alive I think, and one of the museums in town bought eight of his "street pictures" and another exhibited about forty. They were, in general, well received. I admired perhaps five of them, understanding what he was trying to achieve — defeating the distance between his eye and his canvas I think, as most of us try to do. Before this fine flurry of new interest I don't think either photographer ever did a professional assignment, or indeed considered him/herself as a pro.

When I was a 10-year-old Bronxite, my pals, all children of liberal to radical low-income European workers, many of whom had felt the toe of military jackboot on their ass, thought the way to solve the world's problems was for each country to train up their ten best men of sound body AND mind, and have them meet in an Olympics. Winner would be King of the World. Women weren't even considered. Everyone knew they were the real power in the family and that was enough to spur on our champions.

We also wondered if, somewhere on the globe, unschooled in boxing or baseball there languished a baseball player or heavyweight boxer who could beat Babe Ruth or Joe Louis.

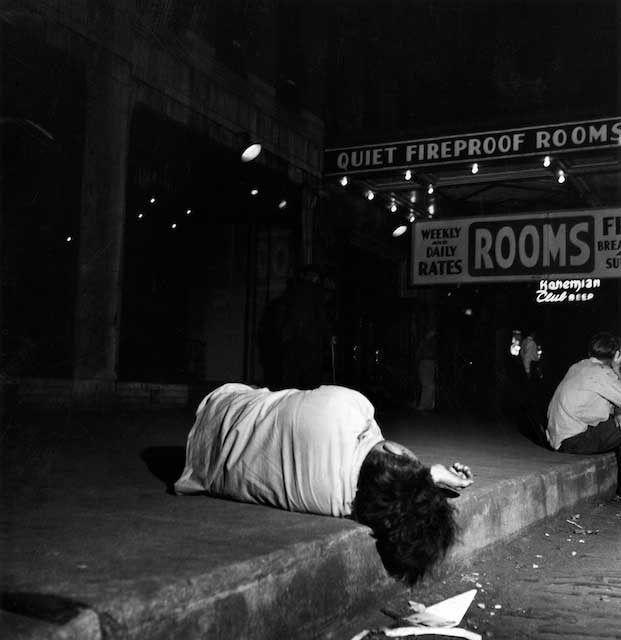

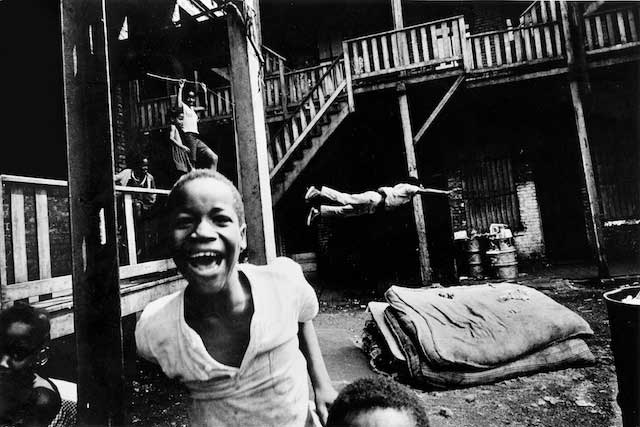

At the same time, atheist George Bernard Shaw, tired of being importuned on every side by wannabe playwrights, artists, poets, novelists and philosophers, was being quoted by London's literati: "Good God - protect me from the gifted amateur." He was of course, mostly thought to be snotty and snobby. In one way or another we are all amateurs of varying degrees of giftedness. And, as Algren pointed out in his own way to me as I followed and led him around Chicago's underside for ten years, "We are all members of one another." He didn't have to add, "Like it or not."

Even though I was a desperately ambitious (and sometimes published) writer, I dared only once to show him a poem I'd written after I soloed but before I washed out of pilot school - before I became a combat navigator. We were driving to New York to see a publisher about a picture book. We were in my '54 yellow Hudson Jet and I showed him the poem at an Ohio rest stop. He read the thing on the inside cover of my Aviation Cadet class book. "You got two great lines," he said of my intergalactic effort. "We are no more than that before us gone." He laughed gently."I may use that some day. The rest is doggerel." In other words, "Kid-forget that typewriter but don't ever lose that Leica."

We once started to collaborate on a TV play about his sad adventures with Otto Preminger in Hollywood. He let a line I wrote stand: "His face had the gray morning look of being hacked out of the hindquarters of adversity." Then he looked at his watch. He reached for his coat. He was late for his poker game and would board the southbound trolley on Broadway at Thorndale near Senn High. "But this scene..." I said lamely. "Easy," he said, "all you gotta do is get Preminger out of his Caddie into this motel room he had me in." And left. I watched that Salvation Army coat - he called it "Salivation Army" - go out my door. The tattered coat, that housed the man I regarded as the best dialect writer since Chekhov, walking out on an important transition in the play he'd been encourage by no one less than Paddy Chayevsky, who had written "Marty" and whose work on love in the lower classes was influenced in Algren's short stories. Or so Chayevsky said to him unsolicited on the phone one morning in his ten buck a month apartment at 1523 Wabansia.

My favorite "influence" anecdote? Chicago-grown movie director Bill Friedkin writing that my pictures of Algren's Chicago had influenced his choice his choice of New York underbelly sites for his drug-chase classic, The French Connection. I had, early in his career of directing 800 Chicago TV shows, delivered 200 of my prints to his mother's small north side apartment, where he studied them intermittently for six months. I was thrilled, advanced amateur that I was becoming, to be noticed by a real pro. When he returned the pictures he said, meaning it as praise, "You ought to get into TV." Long before he outgrew Chicago TV and moved to Hollywood. The producer of the upcoming documentary on Algren by Mike Caplan, head of film and video at Columbia College, recently interviewed Friedkin on this very subject, positioning him in front of one of my pictures.

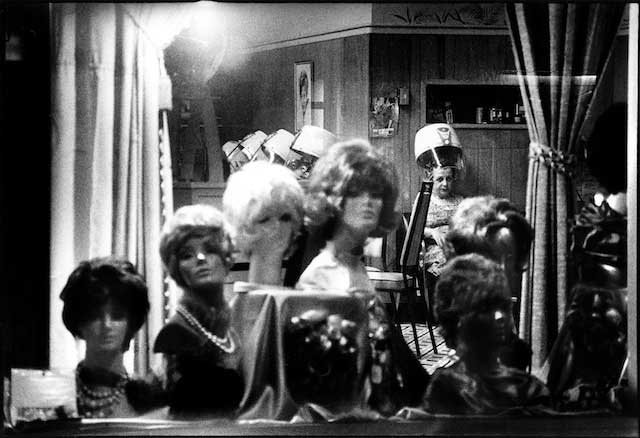

As to the work of Vivian Maier "street photographer" as she's billed for her Cultural Center show that runs through April 3, I intend to attend the March 24 noon "Gallery Talk" by chief curator Lanny Silverman. But before then I want to amplify my first impressions of the late Ms.Maier's work - that it was pleasant and a fine series of character portraits. I could imagine lots of people buying them. Maybe the confining down-looking Rollie format could cost a quick eye some of its speed? Who knows? One result would be "nice" pictures- some of which ran in Chicagoist a few weeks ago, and were accorded a good reception.

I liked them better than my own picture-seller, Daiter Gallery's manager, Paul Berlanga. In his laid back way, Paul, who has the best and most discerning picture eye of ANYONE I ever met, said, to my surprise, "The owner of the negatives offered them to us. I didn't see anything that excited me." Or maybe excited her? I guess that's what I miss in the work of most gifted amateurs, as Shaw, not I, call them disparagingly- the excitement communicated into then out the eye to the rest of us. Our eyes are always hungry for the views that artists present to us. Each of us has to then “process” these views. Or take up our own camera, brush or musical instrument.

Most amateurs tend to take what my Life Editor Ed Thompson used to call "thereness pictures". I think Ed’s lesson to us all was you point your camera at a scene and that’s it. I think he meant he wanted Life photographers to add something-anything of themselves. That soupcon that artists add may be responsible for the grip that art exerts on us- on each in some private way based on the person we are.

Now we may both be wrong- because some viewers and critics have likened Maier’s work to Cartier-Bresson; Paul Strand; Helen Levitt; Lisette; Weegee; Siskind; Callahan and Arbus. It's a tough league - some of Arbus's work goes for $300,000 and the sad biography that came after her suicide notes that she never earned more than $12,000 with her camera in any year. And her commitment or madness or weird excitement was such that she often slept with her grossest subjects.

Art is something each of us must judge for him/herself. I find it hard to believe that two of my recent critics have averred that my work resembles that of Dostoevsky, Hemingway and Melville. One critic has written that my pictures should be used for therapy because the inter-relationships etc etc. Rather I'm still alive enough to shrug my shoulders rather than having to wait until I can't shrug them anymore and won't even be able to call my surviving wife with the exciting news that my prices have tripled overnight just because of my final career move that's made my pictures rarer and more salable.

For my final segment I take you to what's left of traditionally English London. After using his inherited fortune from Beecham Pills to help young amateur musicians get started in the Twenties, Sir Thomas Beecham, conducting the London Symphony Orchestra, with some of these gifted upstarts in it, on the stormy night of Oct. 7, 1932, into the teeth of the Depression, gave a Piccadilly-shocking performance of Berlioz's Carnavale Romain Overture. The audience climbed on their seats and cheered.

From that moment on Sir Thomas became an easy mark for celebrities and Parliament members.They would use all their influence to drag before the great man their amateur, semi-pro and modest professional musician relatives and friends. Sons and daughters of the mighty would trickle into Symphony Hall or Covent Garden following afternoon practice- and one by one shyly play a few bars for this affable music maven of mavens. To find out whether it paid for them to continue practicing- or better, to enter the church, the military, or business. A serious decision.

There appeared before Sir Thomas one day a beautiful young violist, oldest daughter of an important English family. She sat in the audition chair, expensive violin playing position. Sir Thomas, on his chair, lighting his cigar, preparing to listen.

The young lady, hip to her situation, began playing a few bars from Berliosz.

In fifteen seconds Sir Thomas raised his cigar hand and stopped her.

"Young woman," he said, " I must tell you and your family the truth. You have between your legs an instrument capable of giving pleasure to thousands. And all you are doing is scratching it."

She went on to become an actress.

If you can't wait until this time every Wednesday to get your Art Shay fix, please check out the photographer's blog, which is updated regularly. Art Shay's book, Nelson Algren's Chicago, is also available at Amazon.