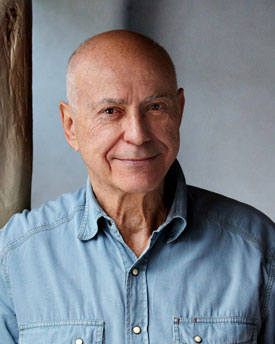

Alan Arkin's Improvised Life

By Rob Christopher in Arts & Entertainment on Mar 1, 2011 4:20PM

When Alan Arkin moved to Chicago in the late '50s it wasn't part of a quest to learn cutting-edge improvisational theater techniques. It was strictly a way to put food on the table. As he recounts in his new memoir, An Improvised Life, "Making that call [to Second City co-founder Paul Sills] was like phoning in my own obituary. Taking this job would absolutely end my chances of doing anything major in either New York or Los Angeles. In no way did I think it would lead to theater, or film. Chicago had no theatrical importance in those days; this felt like a death sentence for my career."

When Alan Arkin moved to Chicago in the late '50s it wasn't part of a quest to learn cutting-edge improvisational theater techniques. It was strictly a way to put food on the table. As he recounts in his new memoir, An Improvised Life, "Making that call [to Second City co-founder Paul Sills] was like phoning in my own obituary. Taking this job would absolutely end my chances of doing anything major in either New York or Los Angeles. In no way did I think it would lead to theater, or film. Chicago had no theatrical importance in those days; this felt like a death sentence for my career."

He might have joined Second City simply to make a living, but it would prove decisive for his future. A few short years later he was playing to sold out audiences on Broadway in Carl Reiner's Enter Laughing; and shortly thereafter in the movies, earning an Oscar nomination for Best Actor for The Russians Are Coming, The Russians Are Coming. He finally won an Oscar in 2007: Best Supporting Actor as the crusty grandpa in Little Miss Sunshine.

He doesn't write about that in his memoir, or about Catch-22, or even very much about Little Murders, the black comedy he directed that remains one of the most shamefully underrated movies of the 1970's. He's Alan Arkin, and he's earned the privilege to damn well write what he wants. For many years now he's been very involved with leading improv workshops, for actors and non-actors alike, and those and other hard-won lessons from the world of acting are front and center. He also touchingly writes about his family, including his son Adam.

We were lucky enough to field a few questions to Mr. Arkin about his time in Chicago, the nature of improv, and the difficulties of film-making.

Chicagoist: Where did you live in Chicago? Can you describe what Old Town was like at the time?

Alan Arkin: When I worked at Second City I lived at a rooming house run by a woman named Emma. It was just around the corner from the club, and Old Town was pretty wild in those days. I met people on a daily basis that were lucky not to be in jail, some of them very fine artists. A whole new series of experiences for me. I became very sophisticated very quickly.

C: Was your work at Second City very political? Did you do a lot of pieces about the mayor and local politics, for example?

AA: The work at Second City was very political, but as I recall most of our targets were mostly national or international figures. I don’t remember very much material about local politics.

Chicagoist: Was anything off limits in your improvisations? Did you ever have to tone something down? How have the techniques you helped develop changed since the early 60’s?

AA: There wasn’t too much that was off limits…we were never censored. But there was very little scatological material…we just didn’t seem to feel that we needed it, nor did we seem to need a great deal of overt sexual content. It was a different time. Subtler.

Chicagoist: Tell us a little bit about the workshops you lead on your own. Do you ever use the workshop format with people you’re already doing a project with, like a play or a film, in order to try out and to build ideas?

AA: I never use the workshop format in projects outside the workshop. The workshop material is very orchestrated; the first quarter is geared mostly toward having people get to know each other and work for each other. It’s a concept you don’t see much in the commercial theater or film. Most of the workshop material would not apply to existing written material.

Chicagoist: Have you ever used video to record your workshops so you can go back and re-watch them later, see what worked and what didn’t?

AA: I have never used video in the workshops. There have been a few offers from documentary filmmakers who wanted to film the whole thing, but it’s been crucial to me that the participants feel safe; that they have a place to stretch out, to experiment and let go, and my feeling is that the minute a camera is pointed at someone they’ll either shut down or start performing. I’d prefer not to see either in the workshops. I know it would stifle me.

Chicagoist: Tell us how your involvement with Little Murders came about. Why did you direct the film? Is it true that Jean-Luc Godard was originally supposed to direct it?

AA: I got involved with the film Little Murders because the Off Broadway production I directed was a very big hit. Godard had apparently been slated to do the film but backed out for some reason or other, and then I got approached. Initially I didn’t want to do it, because I felt I’d pretty much said what I wanted to say with the production I’d directed, but I got convinced, I think by Elliot. And I’m very happy I did get convinced, because it was a dream experience from beginning to end. I’m still very proud of the film. Elliot produced it and he was a joy to work with both as an actor and as a producer.

Chicagoist: You’re a filmmaker yourself, and as an actor you’ve worked with other great filmmakers like John Cassavetes, Steven Soderbergh, and Mike Nichols. All have had their struggles just getting their work produced and seen by audiences. Do you think getting the work out there is sometimes harder than creating it?

AA: I think getting the work out there is always harder than creating it. It’s one of the main reasons I don’t direct anymore. Directors and writers and producers all have hyphens after their professions, the second half being salesmen. I never wanted to be a salesman. It turned my stomach. I’d rather not work at all if I have to spend 4/5th of my time convincing people that it was worth doing. I remember having a conversation with Milos Forman on that subject. He was talking about his first meetings with studio executives. He said to me, “They always ask me what the film is about. I want to answer, how should I know? I’m making the film in order to find out what it’s about!”

Chicagoist: On the one hand, it takes a lot of time and concentration to create a piece of art; on the other hand, as you write at the end of your book, “In the final analysis, it’s all improvisation.” How have you learned this balancing act? What advice do you have for achieving it?

AA: I can’t answer that in one easy paragraph. My best advice is to read the book.

Chicagoist: How can an actor get away from “selling” and just play the part?

AA: You have to constantly remember what you studied and go back to the very beginning each time you audition, each time you get a part. It takes courage and endless self examination. You have to not know the answers and think like a beginner. You have to make yourself available to the work without inflicting yourself on it.