Found Photos: The Story of Chicago's "Little Hawaii" Neighborhood

By Kevin Robinson in Miscellaneous on Apr 1, 2011 2:00PM

A few weeks back reader Kimo "Jim" Noelani contacted Chicagoist with an offer to share some of his family's old photographs with the site. Jim says that shortly after his grandfather passed in February, he was going through some of his old personal items, trying to figure out what needed to stay with the family and what could be donated to Goodwill. Along the way, Jim discovered several boxes of photographs and negatives that gave him (and now us) a glimpse into his past, through the eyes of his grandfather, and a view of a Chicago that many had forgotten. He's has donated most of his grandfather's photographs to the Chicago Hawaiian Historical Society in River Grove for documentation and preservation, but sent along a few for us to share with you, scanned from the original film prints. We reached him by telephone earlier this week.

Jim's grandfather, Haoa "Hank" Noelani first came to the United States in 1912, as a baby.

"Our family came to Chicago shortly after the Navy built Pearl Harbor. Entire Hawaiian families were displaced when the Navy began the project. Andrew Carnegie was thinking about buying a stake in United Fruit at the time, and some of his men were on the island. They realized that the displaced Hawaiians could be brought back to Chicago and used as cheap labor in Carnegie's mills. That's how my family wound up in Chicago."

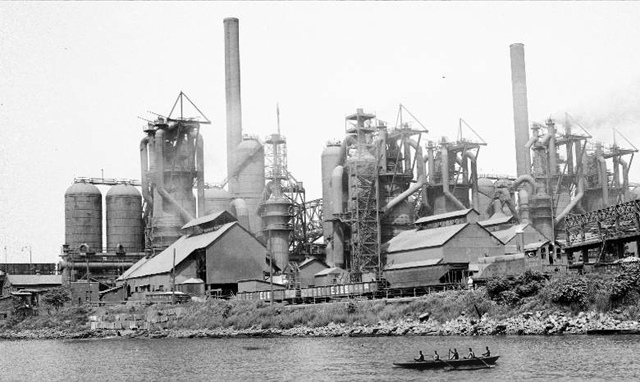

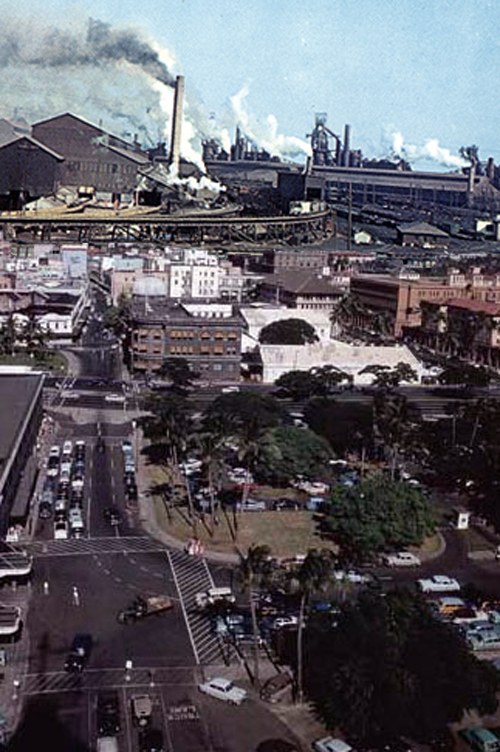

Like hundreds of other Hawaiians, the Noelanis found themselves in a large, dirty, dangerous city, facing dire poverty, ethnic discrimination and cold winters for the first time. With access to more desirable housing shut off to Chicago's newest residents, most ethnic Hawaiians settled in a small corner of the South Chicago neighborhood next to Carnegie's factory, quickly establishing a Pacific ghetto in the Windy City, known then as "Little Hawaii."

"I remember hearing about how bad it was for our people. This was before Hawaii was a state, but even then, it's not like we were accepted by most Americans anyway. My kane [Ed. Note - "Kane" is Hawaiian for grandfather. — CS] wound up having to work in the coke plant at the Southworks, which was one of the worst jobs there was. You walked around this giant coal oven, which was dirty and hot and dangerous. It was outdoors and you had to wear a lot of protective clothing, so you just baked in the summertime and froze in the winter," Jim says.

Those hard times, however, brought the people of Little Hawaii closer together. Jim doesn't remember much of his old neighborhood, since his family moved to Lombard in the early 1980's when Chicago's steel industry fell on hard times, and most of Little Hawaii's residents found themselves out of work. But he does remember his grandfather, and he remembers hearing about growing up, living and working in Chicago from him.

"He was part of a ukulele band. He was really good at it, and he loved to play music. He would go up to Maxwell Street sometimes and play on the street with a few other musicians for fun." Even though living around South Chicago was rough and getting by was hard for the Noelanis, Jim says Hank found great pleasure in his music. "I think it really made him happy, sharing that part of who we were with the world. It was like he was free when he was playing. I can still see his smile."

Although Hawaiians had achieved a modicum of equality on the South side and had risen to the ranks of the lower middle-class thanks to better job opportunities and the mass-unionization of their jobs after World War II, hard times were still in store.

"Layoffs were increasingly more common in the late 1970's," says Jim, whose father Kawika "Karl" Noelani was the last member of his family to be a steelworker. "When the layoffs came, Dad thought we might be alright. He was a millwright, and they were less likely to be downsized. But by the early 80's, it was pretty clear that the Southworks wasn't going to always be there."

That's when the family started thinking about relocating to Lombard. The Noelanis didn't want to give up on their neighborhood, though. Like most folk in Little Hawaii, they were big supporters of Harold Washington, who spoke to their longing for a more stable Chicago and a more equal future. Ironically, one of the largest ethnic groups to leave Chicago en masse was also one of the biggest supporters of Washington.

"In the mid-seventies, some of the younger families left the neighborhood for the western suburbs. The schools were better, crime was lower, there was less pollution. So by the time the mill was shutting down in the 80's, there was already a Hawaiian community out there."

By 1992 the plant's gates had closed for good, and all but a handful of retirees had left for suburbia. Although Little Hawaii remains little more than a memory for most Chicagoans, the neighborhood's last palm tree, a Canary Islands Date Palm, can be viewed at the Garfield Park Conservatory, one of the first gifts of the Chicago Hawaiian Historical Society.