Behind the Scenes at Allen Brothers

By Anthony Todd in Food on Jul 19, 2011 6:00PM

Most people think Chicago's meat producing days are over - that is, if they think about that sort of thing at all. The stockyards, The Jungle; these things have passed into history and legend. We don't do that sort of stuff here anymore. Now we have lofts and boutiques! Wrong. Allen Brothers is still cutting, aging and packing premium meat on the South Side, just like they've been doing since 1893. I went behind the scenes at their Chicago facility to see how real steakhouse steaks were created.

Your intrepid correspondent joined JoAnn Witherell, one of the Vice Presidents of Allen Brothers, donned a ridiculously-oversized insulated coat - the entire facility is refrigerated, all the time - and headed into the loading area. I wasn't quite sure what to expect, after hearing so many horror stories about the abuses of the meat packing industry, but I was pleasantly surprised to see a clean, bloodless facility. "We're a butcher shop, not a slaughterhouse," Witherell reminded me. The facility gets beef in whole loins, so most of the "dirty" work is already done.

Allen Brothers keeps a separate space just for the creation of their prime hamburgers. They do it right - no trimmings, no filler, just prime beef. And everything is constantly tested for any potential contamination. There never is any, but if there is, it's easy to separate off the ground beef room from the rest of the plant.

Dry aging sets Allen Brothers apart from most of the meat industry, which either wet-ages or doesn't age at all. Allen Brothers keeps an entire section of the plant for dry-aging, with fans and blowers constantly moving air over the meat. Dry aging is one of the reasons that Allen Brothers steaks can seem so absurdly expensive - they have to be kept for weeks and weeks, while their weight and moisture content drop and their price increases. The result is a much more tender and flavorful product. On the other hand, the aging loins look like dried up alien husks - and the smell of the aging room, while not unpleasant, can be a bit overwhelmingly beefy. The experience was enough to convince us of the importance of aging - and enough to convince us to leave it to the experts.

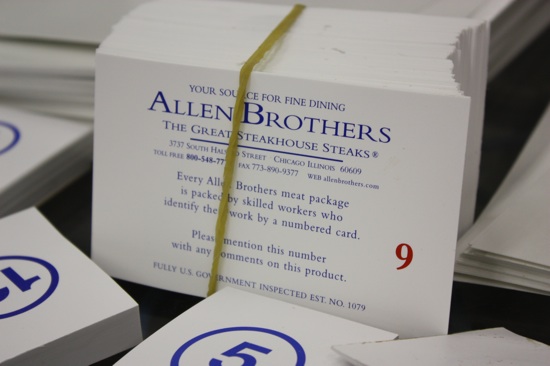

The main butchering floor is quite a sight: steaks being broken down, hamburgers being packaged and labeled, and knives constantly moving. Unlike the horror stories you may have heard from other plants, Allen Brothers runs a union shop of skilled, well-paid butchers, and it takes three years of training to join the business. Meat is cut and packed to order, and shipped out every day. Each retail box comes packaged with the card of the butcher, so any problems can be easily traced. The filet mignons and other prime steaks coming off the line were so perfect as to tempt me to larceny - and the pockets on the huge coat were certainly big enough - but I managed to restrain myself until we left the room.

Many famous steakhouses and restaurants use Allen Brothers meats, including Gene & Georgetti, Charlie Trotters, Haray Caray's and Table Fifty-Two. You can also order the meat retail from their website or catalog, but take a tranquilizer before you do. The price of 4 "complete-trim" 8-ounce filets? $150. On the other hand, if you only eat meat once in a while, it might be worth it to you to get the perfect steak. All Allen Brothers meat is USDA "Prime," a designation given to less than 2% of the beef in America and a grade nearly impossible to find in any supermarket or butcher shop. The best you can usually do is USDA "Choice." So, if you're determined to have the very best steak, and to support a Chicago company, give Allen Brothers a call.