From The Vault Of Art Shay: Studs

By Art Shay in News on May 9, 2012 6:00PM

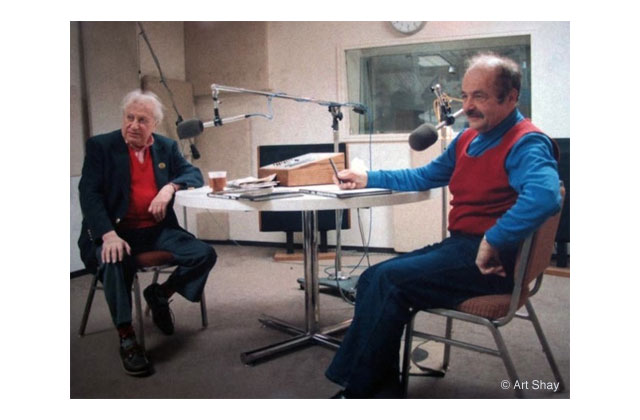

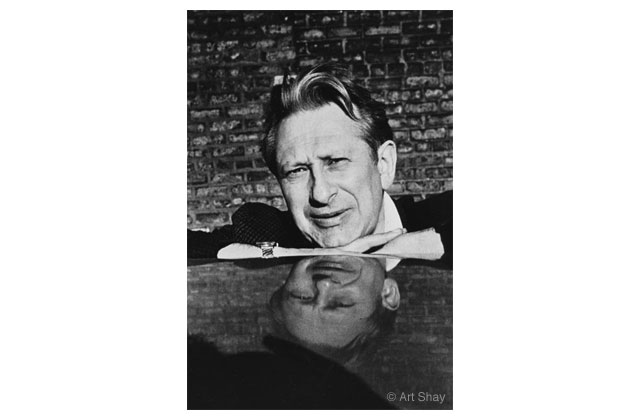

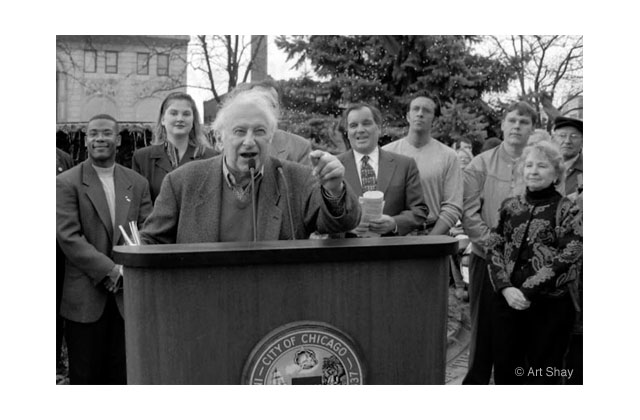

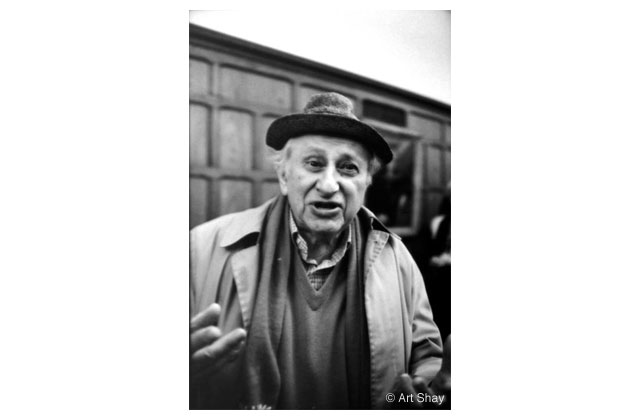

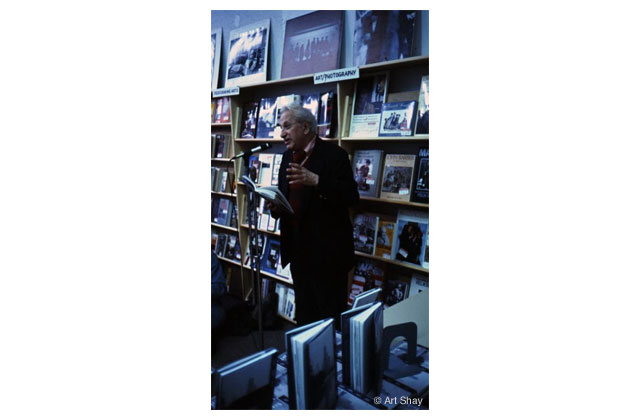

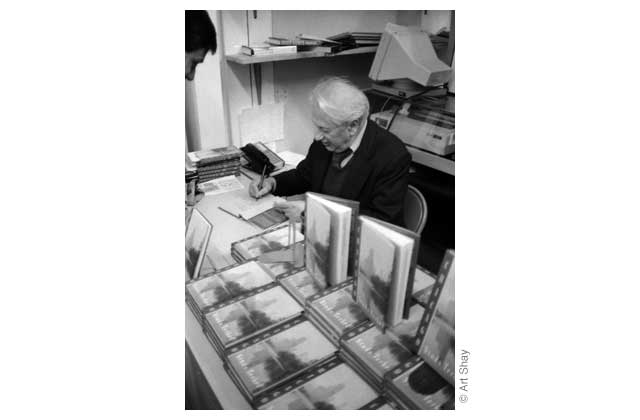

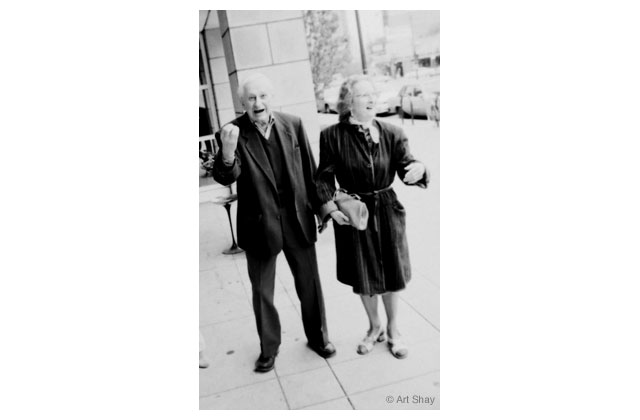

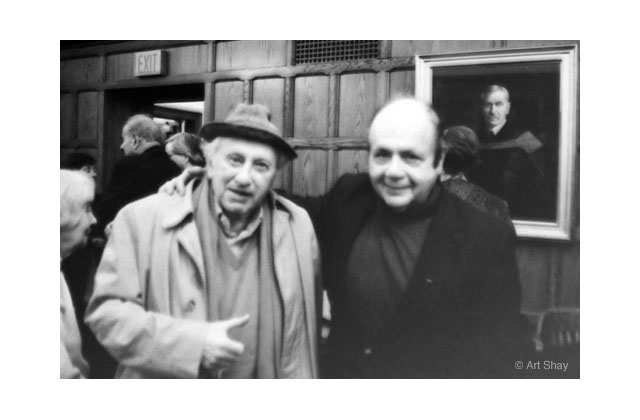

(Legendary Chicago-based photographer Art Shay has taken photos of kings, queens, celebrities and the common man in a 60-year career. In this week's look at his archives, Art remembers the legendary Studs Terkel, who would have been 100 May 16.)

Last year, on the occasion of Studs Terkel's 99th birthday, my dear archivist Erica DeGlopper reminds me, I wrote a well-received encomium on my friend, Nelson Algren's pal and Chicago's icon, who had "come up"—he was fond of growling—"around the time the Titanic went down."

I now ask my sentimental editor and friend, Chuck Sudo, Erica's implicit question: Why not rerun my slightly re-edited tribute of last year?

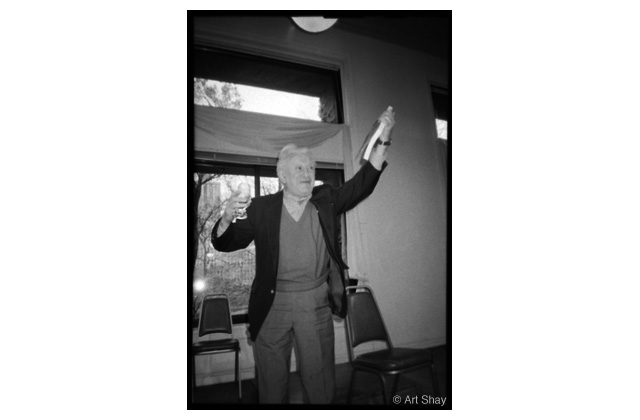

My anniversary admiration, spurred perhaps by my own aching 90-year-old knees, goes back to one of the last times I saw Studs. Without aide, cane or hesitation and to great applause for his feet's feat at 93, he effortlessly climbed the foot and a half Everest step going up the Library's stage to welcome Garrison Keillor and his wonderful literary nonsense to Chicago, the capital of wonderful literary nonsense.

Now that my modest blog has gone international, I hope we can dredge up a few more images I've made of Studs over the years, and illustrate my recycled tribute with them. Especially for new readers in dem dere exotic cities. — Art Shay, Deerfield, Ill.

--------------------------------------------------------------

Originally published May 18, 2011

When Studs Terkel, age 90, came out of his heart surgery anesthetic in 2002, his exultant surgeon, mask and green gown spattered with the little giant's blood and sweat, said , "You're done!"

Skeletal and beat as he was, Studs's eyes flashed as the old performer picked up the comic queue dropped into lap: "You mean this is it? I'm all done? This is the end?" The old ham tried to move his head and arms diminishing this alien theater of healing and affecting to wait for the afterlife attendants to take over. He was ready, as always, to get on with it, wherever the hell it lead. And get there with a twinkle that wafted the ball into the other guy's court.

The successful operation, Chuck Sudo reminded me, led to six more shaky but productive years of life. Monday marked the 99th anniversary of Studs's birth, which as he liked to put it, came "twenty-eight days after the Titanic went down—that's when I came up."

And what a comeuppance for all of us who've spent at least a small part of our lives rooting for the poor, the downtrodden, the perennial losers, the weak,the voiceless, the ugly and the powerless. At the head of our brigade of would-be do-gooders of all stripes—way out there at the head—was Studs. Leading. Questioning. Puffing cigar smoke out with his apercus. Like: "You say you're a simple packing house worker with no point of view? That's bull buddy. That is a point of view. C'mon. What did management do to start this strike? Or did they?" And in counterpoint, manager and worker spouted their venom until, with Studs's orchestration, venom transmogrified into serum. A hundred times, on dozens of picket lines, in many a Chicago slum. Backstage, onstage, during the game, after it was history. The who and the why were his stock in trade. And what a high flying stock. for a cat who was a jazz expert, a sports nut, and an actor set down for all time in Eight Men Out.

From the lips of Claire Hellstern, a nurse to Studs's tape recorder in 2001's Will the Circle be Unbroken?:

"I'm walking down the street and a young man about nineteen pulled a switchblade out of his sleeve. I had only seen these in movies, switchblades. It flipped open. I was kind of fascinated. He said, 'I want your wallet.' I handed him my wallet and he says, 'Only ninety cents?' I said, 'Buddy, I've had my purse stolen six times. Do I look stupid? I don't carry much money on me- I don't make much money. And I've got to go open the clinic.' He returned the the wallet and said, 'Give me the whole purse!' I said, 'Young man, I know you use my type of comb, and you don't wear lipstick. I'd hate to have gossipers talking about you walking around with a lady's purse.' I knew he was a novice. He had the switchblade at his side—not up to my neck—when I'd have done anything to survive, even his cooking. When he realized I wasn't gonna cough up anything he was so stunned, he bowed and said, 'After you.' So I said, 'No buster, after you.' Like a lady and gentleman. All of a sudden his manners kicked in, and he ran away. And I had tears. Not so much scared as ticked off."

Not unlike the story Chaz Ebert, filling in for her voiceless husband, Roger, drew out of Studs on stage: how when he was held up far from his North side apartment, he reminded the thief he hadn't even left him any carfare to get home. The thief softened—or as Chaz put it, "humanized"—and gave Studs the fare home.

Other Chicago icons like Dr. Quentin Reynolds have said Studs's work would, in 200 years, be the go-to history of our time. Chicago's best historian and Studs's greatest fan, Garry Wills, noted how Studs, a University of Chicago law graduate, once used his deafness to cool off stuffy law prof Richard Posner purposely mis-hearing then misquoting Posner as (hand cupped to ear) saying he taught "avarice," not "evidence," to his young would-be shysters. As Hemingway said of Terkel's pal Algren, "He could hit with either hand." And from anywhere. And make it stick. James Baldwin would pick up Studs's reminder that the eight-hour work day was born in Chicago in 1886 and liken Studs's work to that of Tom Paine during the American revolution. Common Sense is what it was called.

Film maker and radical Haskell Wexler called Studs's sashay down Liberal Alley a saunter down "one street"... "Our Street". You know who "our" is: all of us hated liberals of the past 70 years. Consumers of a trillion in Medicare while 13 trillion goes to our vaunted armed forces in their aggressive defense of freedom and its attendant fossil fuels. (Note to anti-liberal critics: I've written more than 50 books and done 1,100 photo covers. I flew 52 combat missions over Europe, hold five Air Medals, one for shooting down a Focke Wulf 190 at 60 yards, the DFC and the French Croix de Guerre. I led 1,100 B-24 bombers to Berlin. I spent eight months flying the Pacific wounded home, and flew MacArthur's Occupation staff into Japan. I was a National Racquetball singles and State champion in 1982 and the Bugle Champ of the East Bronx in 1935. Plus I had nine months of college in all. So there.)

Studs didn't mind criticism or mild competition, but he suffered fools poorly. One of his network competitors for the lady-trade of the houseworking set was Paul Gibson. Studs claimed it was Gibson's slow stetorian voice that got the lauds "and made them think his windbaggery and empty sub-Reader's Digest fluff was wisdom." I remember one lunch I shared with Studs, Nelson Algren and Herman Kogan where the subject was Arthur Godfrey's radio boast that he had shot an elephant in Kenya at 30 yards—to secure matching umbrella stands made of the poor thing's feet. The defense of defenseless animals made Godfrey and his network back off. (This was, of course, before Jon Stewart was born.) But in part Stewart exists because Studs was brave enough to take on the gig guys, usually using, as Stewart does, their own words and deeds to jab them into a consciousness that someone is watching. How Studs would have exulted in the story of Newt Gingrich's infidelity while attacking Bill Clinton for the same in Congress. His later defense: his adultery was designed to strengthen his political chops. Something like that. Our current history did have beginnings.

Early on, while running Stud's Place, a fictional TV joint with Beverly Younger as smarmy waitress, I remember one interview Studs did with Chicago TV's brilliant Dave Garroway.

"You looked out your window and you saw these two kids making out in the rear seat of your convertible?" "Yeah- then the boy climbed over the seat started he car and drove away." "So what did you do, Dave?" "I did what any red blooded American citizen would do: I took down the license number."

Has Letterman or the chubby one who collects cars said anything that funny in the past several seasons?

I had occasion the other day to drive past the modest little house in Highwood where the great magazine writer, and my sometimes colleague, John Bartlow Martin coined the "vast wasteland" description of TV for the 1961 head of the Federal Communications system, the brilliant Chicagoan Newton Minow. It was Minow, with Martin's prodding ,and that of their smart friends,partly encouraged by the mocking Mark Twain-ishness of Studs in their time, who caught the ear of Adlai Stevenson and JFK about the coming catastrophe of uncontrolled TV. In its rush to what my Uncle Izzy would call "its pinochle" the recent royal wedding atrocity included the note of one Chicago columnist. It was picked up by one of those "back to you Robin" ladies- who echoed the printed vital question: would the Prince kiss the Princess once or twice after the wedding?

As I suggested to you a couple of weeks ago, I heard Simone de Beauvoir describe her interview with Studs in English to Nelson Algren, as she jotted a note on it in French, to her other man, Jean Paul Sartre. She said, "It's like being denuded by a man so expert, you do not mind it." When Studs expressed his disappointment that his brilliant son Dan was driving a cab, Nelson comforted him. "Hey it's a good way for him to meet people."

Studs brightened up. "Yeah, Nels, you gotta look at the bright side."

If you can't wait until this time every Wednesday to get your Art Shay fix, please check out the photographer's blog, which is updated regularly. Art Shay's book, Chicago's Nelson Algren, is also available at Amazon.