From The Vault Of Art Shay: My Great War

By Art Shay in Arts & Entertainment on May 28, 2012 6:00PM

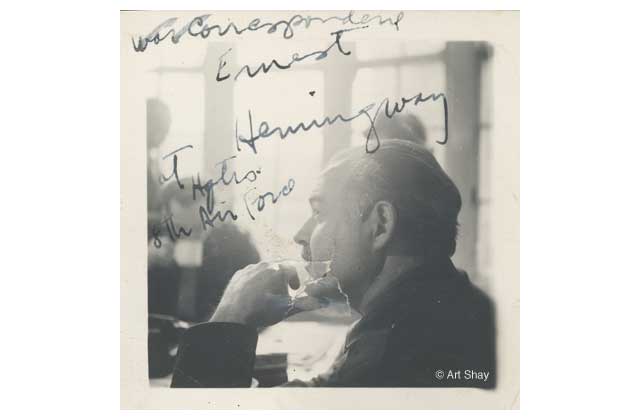

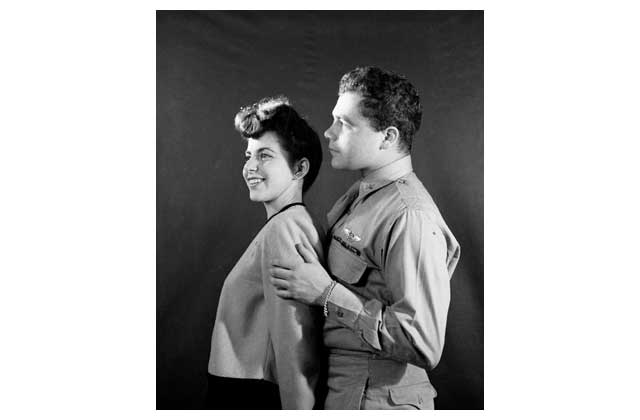

(Legendary Chicago-based photographer Art Shay has taken photos of kings, queens, celebrities and the common man in a 60-year career. In this week's look at his archives, Art looks back at his World Ward II military service.)

The Washington Post

June 9, 1946

H-Hour (Do Your Remember, Dear ?) Was a Million Minutes Ago…

First Lieut. Arthur Shay of Brooklyn saw D-Day from

a Liberator, and two years later, last Thursday, wrote

the following poem as a memorial-and a protest. Just

out of (a semester of ) college in 1942, he entered the Army as an air

cadet. He flew 30 missions over Europe as lead naviga-

tor in a B-24 squadron, furloughed briefly in this

country and went back overseas for a top-secret Air

Transport Command job-flying in and out of neutral

Sweden. He didn’t get to the Pacific until after

VJ-Day and flew the transport C-54's that took the wounded home- from Australia, New Guinea, Hawaii, Japan---He navigated the MacArthur occupation team from Guam to Tokyo.

(Ed. Note: Art is in the 1946 Aviation Record Book for navigating a B-29 Air Weather Service plane from San Francisco to Anchorage in 13 hours, at 30 feet altitude, pioneering blind flying by weather isobars. The Air Force still regards this as too dangerous for common use.)

He is now attached to the Office of Informa-

tion Services at the Pentagon. He has written poetry

for the British magazine Courier and the London Times,

and the following verse will be incorporated in a book,

“Heaven’s Cheapest Seat.”

By Arthur Shay

There is the boy-voiced orderly who stumbles in your

sleep and checks your face with something halfway

down his list.

The hut is cold and English rain has lost its kiss, is

vicious on the metal roof,

And you live between two air raid shelters.

He came in an open jeep, his young face smarting

with the weather and his own awakening.

First nudge and he’s your little brother waking you

in time for school,

Transferring your mother’s admonition half the

Nissen-hut length all the way to home.

“You’re flying, sir,” he says. “Briefing at 3.”

“Roger,” you say, “Roger.”

(One of those war words, darling, easy to say, caught

on quickly, like “Veteran” and “GI Joe.”)

You stumble from the hut to washing . Bare feet take squishy

traction on the wet grass, then waking to the little,

chatter of the others, cold with the same dull fear,

frozen by the sacramental tap-water. Maybe today.

(Your morning kiss is warm-awakening from the

happy catalogue of our marriage,

My joy assailed only by our homelessness, framed

for me in my eye’s dim compass of these dirty walls.

Nor have we a kitchen in which to build a chain of

breakfasts together in our sleeping clothes.)

* * * *

They hand you breakfast, casual as automats. You

smile. (KP’s are meagerly repaid

And by the way, how do the British win their wars

with food like this?)

Listen to the stumble-conversations, subway talk

between the stations as you studied on the train.

The raucous yell, “Big B today!” The lollards, those

with time for cereal and cream, think not.

The coast- a milk-run-maybe, at the worst, Calais,

Where all the flak is accurate but bunched.

Or will this be the Day of shining effort, D-Day, and

thrust across the water?

Rumors spiked, destroyed and thrown at the German,

sitting on positions heavy with four fat years.

(Darling, the Chinese are still fighting in the hon-

orable shadow of their crude wall,

Defense project of a thousand years ago. Great walls

are quickly obsolete, for ladders are groats in history.)

* * * *

Ask a general. (That’s what they told me, sweetheart,

when I tried to buy a car,

A surplus car, and a surplus typewriter for our busi-

ness. If we ever find a surplus office. ) Ask a general.

Once a general gave me some medals. He said

“Thank you” and shook my hand. A swell guy—(there’s

no caste among officers.)

He’d shake hands again if I saw him, but the cars

are in Atlanta and that’s far away.

(Berlin was 1200 miles away , but a state of peace exists

and Atlanta’s in Georgia and the papers are filed on

the West Coast.)

* * * *

Briefing room, annoyingly like what the movies

think- (Haven’t seen Van Johnson in an Air Force

picture in a long time.)

Wall-map, half a world on half a wall. The business of the meeting is brief: If you don’t hit this, hit

something.

Bombing is blind man’s buff with radar.

Outside the many-engined hum, insistent spinners

sipping fifty gallons in a rainy dawn, just warming;

Cocktails for four drunken engines.

The major jests—no fighter cover. Cheek-face major,

he who led the last-time raid, describes the target . . .

(What sort of job can a raid-leader have now? Oh- this one died three missions on.)

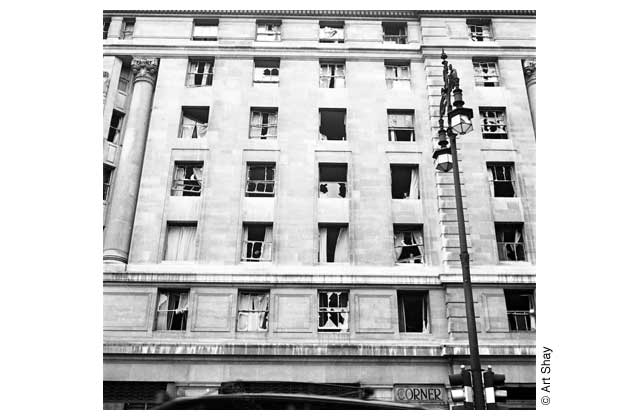

“. . . forty flak guns, important rail and communica-

tions target, making it easy for the TASK FORCE.”

Invasion. Invasion. It is a little word with a large

tail. This is the day we spit in Hitler’s eye.

Will they put it off? Should have been yesterday,

you know. Weather? Equipment?

Certainly not a manpower shortage, and don’t tell us

men are readied and lubricated for battle quicker than

machines.

(Who knows? Maybe a fist war would be over in a

day.)

* * * *

“You’ll be skirting Paris—lots if pretty babes

down there, don’t hurt ‘em.”

(The impossible we do at once. Hurt? As if we were

equipped with pain to give and take.

It’s hard to hear a scream at twenty thousand feet,

but I heard you scream, Florence, getting the telegram,

Closing my life account with Living, Incorporated.

A million telegrams could say not a single word past

“one of us is dead.”)

Like planning a snowball fight in an alley. We’re

the good guys.

Brother-winks of bombardiers, union in profession,

death-dealers to the throne, by appointment only,

And they only work here like the rest of us.

Maps are marked “restricted”—did you know?

AS IF THEY DON’T KNOW WHERE WE ARE!

Brave New World, Limited.

The documents are signed and we are almost ready.

Received, three hundred thousand dollars worth of

plane and bombs, ten men.

(“Six months at the least, mister. Lots of veterans.

Lots of applications—has to go through channels and

it will cost plenty”.)

What channels lie between zero and twenty thousand

feet, and how much per foot is altitude on two engines?

* * * *

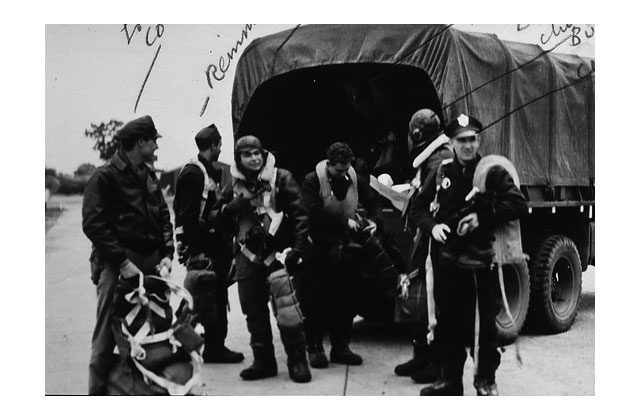

Lorry ride across the bumpy ramp to Sweet Sue. Solemnly

ten kisses on her nose.

A secret rite performed in the privacy of a cold

hardstand.

(Did not Hannibal fondle his elephant? And you

can’t feed a Lib sugar.)

Take-off!

Pushing from the callow earth with muscles wrought

by women sixty hundred miles away at Willow Run.

(Are they still working there, honey, or do men build

Kaiser cars?

Did Mr. Seybal make another pass at you?

I’ll kill him when I get back. When I get back.

We’ll have each other, and the world will be for us.

Darling, have you stormed a nylon line?)

* * * *

The low dawn rises, gold upon your silver, clashing

in a fairy-story forge.

(If this be my last dawn, assuredly I’ll not die alone.

Beaches will be blood- crimson as we cross them,

Death will comb the Norman beach, tide will race

him for the spoil, war’s omnipresent surplus.)

Will the boys down there look up and call us lucky?

We who sleep in English beds and fight an eight-hour

day?

* * * *

Your voice is metal, slowly sharpening to the micro-

phone. You call the compass heading, thwart the

crafty wind.

Pilot answers “Roger.” settles down. Ten men become

one instrument, a hundred planes are ten.

Gunner spots the London Bridge, looks down.

“Blimey,” someone laughs.

A thousand ships sit in the dirty Thames without a

Helen.

Finally the coast at Land’s End. Now we are of the

countless men who left England on brave purpose.

There they are, thick in the channel and four abreast.

Two thousand at least.

History for the looking. Like cars from a tall build-

ing, crawling down Broadway.

Kiddie-cars, each with its toy balloon and apostrophe

of smoke.

Busy-bee fighter planes, like hawkers at the Stadium,

selling safety to the convoy, hovering at three hundred

per.

Up and down.

Ahead the broken-cup coastline, and look at the dots

on the beach.

War’s punctuation and Hell’s private diacriticals.

The parade moves slowly.

Le Havre sits off the left wingtip, Cherbourg upon

the other, Caen over to the west.

No flak yet, save the spineless stuff that breaks too

low.

(Are we feeding them breakfast today, and have

they forgotten how to hit a Liberator?)

Your shadow moves across an undercast. The ceiling

changes. In navigation school you didn’t fly on cloudy

days.

A thousand years ago in Texas.

(Remember Mary Anne in Texas? You were so

jealous, darling.)

Remember the Alamo?

* * * *

Take your flak suit off, be brave and throw it on the

floor.

Nudge the bombardier aside, his work comes later—

(Chuck Bunting is still in the hospital-broke his back on a training mission, crashing on Tom Paine's farm! These are still the times that try men's souls! And we owe him a letter. He's never gotten over the Dear John letter his wife sent to him )

—after all, we’re paving the way as the Colonel

said, paying with rubble.

Bet you a million dollars we’ll rebuild the whole

mess.

Try to see Alencon from out the nose—the goddam

clouds again.

You order turn on time. Distance, rate, and time.

Was it seventh grade? No pigtails to pull in flying

school.

Change positions. Steady now. Chartres is dead

ahead. Initial point

* * * *

You call for bomb bay doors to open (somewhere

today is a navigator now a doorman?)

Then you’re on your run.

Bombardier is on his knees across his Sperry sight.

The other ships will bomb on us today. We drop smoke flares with every load-

When the lagging planes fly through our contrails , POW, they drop their bombs too.

“Flak!” a gunner says, “at three o’clock.” All eyes

turn right.

Six black puff-clouds, close but high, no damage.

Then a dozen bursts (those boys are sharp)

And metal bounces through the ship, no damage

Tracking fire! Lib aflame at nine o’clock—two chutes.

We are ducks and they are hunters—from an airfield,

Ecrosnes you say, as if it helped.

Hold the course and hold the airspeed, bombing is

an art, an art.

Saint Cyr bears east—French West Point, you know,

the German billet ...

Bombs away! Tag, you’re it!

Tail gunner sees them hit.

You chart the bursts on target photos; were people

riding in those trains?

More flak. Group astern is catching Hell.

The Eiffel Tower - straining you find it north of target.

Flak again.

“Three-thirty-two—Three-Three-Two,” you say, allow-

ing time for turn. Now!

* * * *

The pilot turns. Your buddy Cecil, swings your thirty B. Isom of Ennis, Texas ,

Swings our tons of death to north and west. Guided by a kid from the Bronx who had trouble passing plane geometry!

Sweet Sue is going home.

Les Champs is straight and white, can’t find Les

Tuilleries. (From where my Dad went up in a hot air balloon in 1917.)

Beauvais to the right. Four degrees left.

Another turn. Some flak from near Dieppe, then out

into the blessed Channel.

* * * *

Alter course for home. You breathe again and

oxygen is sweet.

Wagner asks, “Sir, we getting back in time for chow?”

Tail says, “Z for Zebra’s falling back, two engines

feathered.”

Formation loosens, boats again—two hundred, four

abreast, and steaming south.

Letting down, thirty-three minutes to base. Another

windshift, alter course again.

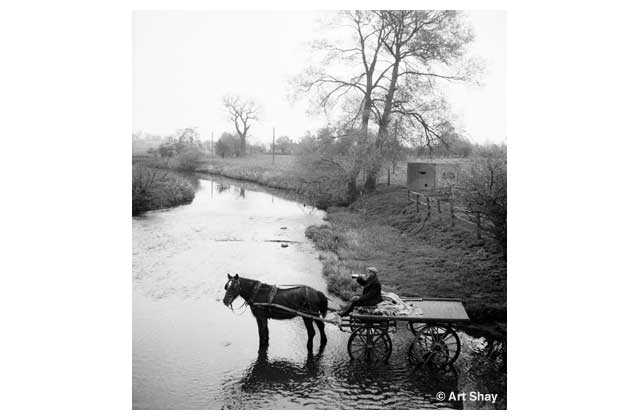

The coast, the beautiful English coast.

We cross it lower than before, the pattern varies,

but who questions St. Peter at the gate?

Then homeward, over eight green airfields, ours the

ninth.

(Sweetheart, airfields look alike, like soldiers and

problems form a distance.)

Camouflaged, but unmistaken, home.

Peel off, using east-west runway. Down.

* * * *

Ground crew, eager for the damage, counts us as

we touch to earth. Our commander, Col. Jimmy Stewart , will debrief us!

("Did you actually see where your bombs hit or are you assuming lieutenant?"

That shyly concise movie smile. He'll be a general before the year is out.)

Ambulances wait. Red-crossed horses at the barrier.

We’ve started to reverse the Hitler legend. This

putsch is on us.

“How’s the invasion, Lieutenant? This your tenth

mission?” says the crew chief, fingering a flak break.

Interrogation, hot coffee. Dull today. Photos will

supply the answers. Flak here and here and here and

here. You transfer X’s from your map to his.

Beaming Major feeds you candy bars.(Did you have

a shortage here, darling?)

Little boys come home for dinner, errand flown as

briefed.

Food and sleep.

* * * *

And overheard the buoyant Heaven holds cheapest

that to it most dear. The lives of young warriors.

(I’m afraid to fly now, sweetheart, and I won’t if you

say.)

The pattern of the Free New Europe, thrust upon

another generation.

(Where are the million unborn families escaping

the famine?)

To blackened Ruhrs and shattered Hamburgs, east

to proud Berlin we march.

Little boys with man-hearts, (We’re older now, wife,

and our hearts are fires of impatience.)

Playing death-tag with the kids across the way in

thunderous millions.

If you can't wait until this time every Wednesday to get your Art Shay fix, please check out the photographer's blog, which is updated regularly. Art Shay's book, Nelson Algren's Chicago, is also available at Amazon.