INTERVIEW: Directors Coodie & Chike Talk Ben Wilson and ESPN's 30 For 30

By Chuck Sudo in Arts & Entertainment on Oct 23, 2012 7:30PM

Coodie Simmons (left) and Chike Ozah. (Photo courtesy ESPN)

In November 1984, the world was shaping up to be Ben Wilson’s oyster. The Simeon High School boys’ basketball team was the defending Illinois state champion. Wilson, the team’s star, was regarded by talent scouts as the best high school basketball player in the country—the first Chicago high school player to attain this honor. A growth spurt resulted in Wilson standing six-foot-nine, yet he retained the grace and skills of a point guard. ESPN’s Scoop Jackson wrote that Wilson was “Magic Johnson with 30-foot range.” Rapper and actor Common said Wilson had the necessary intangibles to be a superstar: a magnetic personality; a sweet-natured temperament; and basketball skills to make others jealous.

Ben Wilson was killed on Nov. 20, 1984, during an argument with two other young men the day before he was to kick off his senior season. Wilson’s murder galvanized a city that, even then, was racked by senseless violence on its South and West sides, and the event served as a rallying point for Chicago’s black community, feeling a renewed sense of pride with a black mayor in Harold Washington and a rookie guard for the Chicago Bulls named Michael Jordan.

Wilson’s life and tragic death is the subject of Benji, the latest documentary in ESPN’s 30 for 30 film series, premiering on ESPN tonight at 8 p.m. Eastern/5 p.m. Pacific. Benji, which was the centerpiece of ESPN’s contributions to this year’s Tribeca Film Festival, was directed by the team of Coodie Simmons and Chike Ozah. Coodie & Chike, as they’re known professionally, are best known for the music videos they directed for Mos Def, Christina Aguilera, Erykah Badu and, notably, Kanye West. Simmons was an early champion of West’s work and filmed the pre-“Louis Vuitton Don” on his early rise to superstardom. West’s “Through the Wire” video still stands today as Coodie & Chike’s most recognizable work.

Chicagoist spoke with Coodie & Chike about how the Benji project started, their signature stylistic tics they incorporated into the documentary, and how Wilson’s death still marks Simeon to this day.

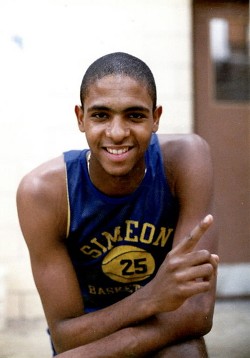

Ben Wilson (Photo courtesy ESPN)

Coodie Simmons: I was in seventh grade and Ben Wilson, to me and my friends, was the man. 1984 was a great summer and we would follow Ben wherever we knew he was playing. When he died, it was like we lost a part of our own family, because he made us proud to be from the South side of Chicago.

Chike Ozah: I grew up in New Orleans, so I had no idea about this story until Coodie told me. I didn’t live with the story like he did.

C: Were you able to sympathize with the story and how, in some ways, it paralleled with other tales of athletes who died before they fulfilled their promise, like Len Bias, Hank Gathers and Reggie Lewis?

C.O.: Absolutely. But Ben’s story was more tragic because, from everyone we spoke with for the doc, he was a great kid. Everyone seemed to love him—everyone.

C: What types of footage were you able to find for the film?

C. S.: My sister Wendy was able to obtain news archives of the funeral. Our main researcher Ryan Goldberg was able to find footage from an Adidas camp an old lady in Milwaukee had in her possession. There’s this group named Chucki Vision that’s been filming Chicago hoops, especially prep ball, for years. They had some good footage of Ben playing ball.

C: You have folks like R. Kelly, Common, and ESPN’s Michael Wilbon talking about Wilson. But you were able to get friends, family and some teammates to open up for the first time about his death. How were you able to break through that wall?

C.O: We almost didn’t. Lots of folks didn’t want to talk with us about Ben. Then we got (Wilson friend) Mario Coleman to talk to us, and he spearheaded contacting them. Mario was the bridge.

C.S.: (Wilson’s friend and former NBA star) Nick Anderson was very reluctant to speak with us. I think most of them didn’t want to open up old wounds.

C: Were you able to speak to modern Simeon stars about Wilson’s impact on the school and program?

C.O.: We got Jabari Parker (the current top prep basketball prospect in the country) to speak with us at the last second.

C.S.: Simeon’s coach Robert Smith mostly runs the program the way Bob Hambric did before him. And Ben’s legacy lives on in the players who’ve worn his jersey number after him—guys like Nick Anderson and Derrick Rose. I also think the team and the school became closer after Ben died, and that sense of family still endures.

C: How did you start the process of filming the documentary?

C.O: We shot the interviews first, then went into the game and archive footage to see what we wanted to use and how everything tied together.

C: What about some of the stylistic things you’re known for, like combining animation and storyboarding with live footage to tell the narrative? How much did you rely on that?

C.O: It’s there, but what we hoped to achieve was to let the illustrations juxtapose with the live footage to complement the story.

C.S.: We were more interested in letting Ben’s friends and family, and the old footage, tell the story.

C: How long did you work on the film?

C.S.: We researched this for seven years, but once ESPN greenlit the film, it took a few months. We started in August 2011 and we completed it in April.

C: Coodie, you lived through this and know how rough the South Side of Chicago was then and now. Did you draw any comparisons between Ben Wilson’s death and the jump in the murder rate this year that’s made national headlines?

C.S: no, but I can see how some people can make that comparison. With the gangs and segregation in Chicago, it’s easy. But what happened here was you had a group of kids who didn’t want to get punked. If they walked away, it’s entirely possible this wouldn’t have happened.