In Pictures: Making 2,500 Doughnuts A Day At Glazed And Infused

By Anthony Todd in Food on Dec 13, 2012 6:40PM

Everybody loves doughnuts. They're so simple, so indulgent and, really, so inexpensive. A new crop of doughnut shops has been raising the bar in Chicago for this simple pastry for about two years now, and doughnut-mania may be at its peak. At the forefront of the movement is mini-chain Glazed and Infused, which opened its first location earlier this year. Unlike the other boutique doughnut shops in Chicago, G&I doesn't produce doughnuts at each of their storefronts. Rather, all of the doughnuts for the entire operation (sometimes as many as 2,500 per day) come out of one small basement kitchen on West Fulton Market. How can a kitchen the size of my apartment create doughnuts for a whole empire? Was it a paradise of pastry waiting to be discovered? Would they let me dive into the vats of frosting? I dragged myself out of bed at 3 a.m. to find out.

This isn't a normal bakery, where work starts early in the morning. Doughnut-making on this scale has to start the night before. Every night, while you are eating dinner, the team of doughnut producers is starting their work. "We start the night before, fairly early," explained General Manager James Gray. "We may be in here at 6 in the evening. Everything happens really quickly over the course of about midnight to 4 a.m. Then everything gets packed up and shipped out." So my 3 a.m. wakeup? That's normal for Gray. I suddenly felt sheepish.

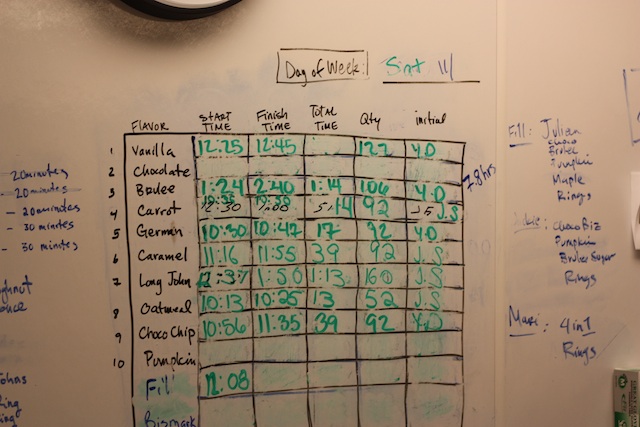

In order to keep track of that enormous volume of pastry, every available wall surface in the kitchen is panelled with dry-erase boards, and charts and graphs dominate. Doughnut making is calibrated down to the minute in order to cram maximum production out of the limited cooking space. At this point, rather than producing doughnut continuously all day, the majority of the production is done in the early morning, with the possibility of making more if it's a particularly busy day. That will likely change when the new Armitage location opens. Gray expects production to increase by 50 percent, and since the Armitage location will stay open until 7 p.m. (and the Wicker Park location sells late at night on the weekends) doughnut production will have to ramp up even further.

Downstairs in the kitchen, the front half of the building is devoted to dough-making and frying. Doughnut fryers, it turns out, are a particularly terrifying piece of kitchen equipment. It's the same basic idea as a standard restaurant fryer, except instead of a small pot of oil with a fry basket, it's a huge open pit of oil several feet across. I imagine it's what hell looks like, if hell was a major appliance. The two doughnut fryers crank out doughnut constantly during my visit.

Gray explains that there are two primary types of doughnut. Yeast doughnuts have, well, yeast, and are more like a traditional bread or pastry. The dough is formed, shaped, left to rise in a proofer and then put into the fryer. For yeast doughnuts, a whole tray of doughnut is slipped into the fryer all at once. As they fry, they are deftly flipped, one at a time, by the cooks using what look like long, dark chopsticks. Remember, everything at Glazed and Infused is made by hand. All of them come out of the oil at the same time on a giant wire rack. Then, they are filled and frosted.

Cake doughnut are made out of a batter that contains butter, eggs and milk. Because they have so much more moisture and fat, they keep much longer. To make them, the cook uses a large dispensing machine. Click-plop, click-plop - each round of batter drops directly into the oil and, after a few seconds, reappears, sizzling on top of the oil. Just like the yeast doughnuts, each one must be flipped, by hand.

Once the doughnuts are fried, they move over to the finishing side of the kitchen. Soon, this part of the process will move upstairs, both to provide more space and to make the donuts lighter. Lighter? "We don't have an elevator," Grey admits. "Every doughnut is carried upstairs by hand." Once the finishing kitchen is upstairs, bakers won't have to schlep 2500 filled and frosted doughnuts up - just the empty shells.

The finishing kitchen is where the doughnut turn from anonymous, un-appetizing light brown lumps into the beautiful products seen under the cafe glass. Ever wonder how filled doughnuts get filled? I imagined that some pour soul with a pastry bag had to fill them by hand. Nope - they'll explode if you make them too fast. G&I has a special machine that injects the doughnuts with the precise amount of filling needed. Bakers slip each doughnut on and off the filling tubes, and the machine makes the place look like a particularly tasty biology lab.

Doughnut making is a fairly labor-intensive exercise. Each of G&I's creme brulee doughnuts is torched by hand. Every maple-bacon long john is frosted with a pastry bag. And the glazed doughnuts? That's the most fun part of all. I had some naive idea that the glaze was painted on each doughnut. Instead, a baker wheels in a garbage-can sized vat filled with vanilla glaze. Using a huge cup, she pours glaze over a whole rack of doughnuts until they are coated. The extra glaze collects in a tray underneath and is re-used.

How does someone get into the world of large-scale doughnut production? "I'm originally from Chicago, but moved to Pittsburgh 7 years ago and opened up a small bakery," Grey explained. "We got a lot of recognition and were able to expand, and we ended up with five locations around the Pittsburgh area." After a few more years, he decided to sell the business and move back home. Turns out that people with large-scale bakery management experience are few and far between, so once Glazed and Infused started to expand, they snapped him right up. The big question: Does he still eat doughnuts? "I've been in the bakery business for a very long time, so dessert is something that i make for other people. It's not something I make for myself." Very diplomatic.

As the morning progresses, racks of finished doughnuts of all types are carried upstairs. I watch a baker lay individual strips of maple-glazed bacon, fresh from the oven, onto long johns and see candied carrot sprinkled on the carrot cake doughnuts. For those who wonder why fancy donuts cost $3 - this is why. Everything is done by hand, and the ingredients are real.

Sometimes, the bakery is presented with strange requests. While I'm watching, Grey is pulled away by one of his chefs to discuss the weekend's big project: a catering company wants 10,000 mini doughnuts. You might think that producing enough pastry to feed a small town would faze the bakers, but they just take it in stride. People have ordered monogrammed doughnuts, speciality flavors - even a doughnut wedding cake. "Doing the fun stuff helps keep everyone motivated," says Grey. Seasonal flavors are rotated in and out - right now, an egg nog bourbon doughnut, a gingerbread old fashioned and a candy cane doughnut are in the rotation. They are even making a doughnut buche de noel.

The sun is finally peeking up over the horizon as we come back upstairs at 6:30, and a few early customers are buying doughnuts and coffee. I almost want to try to tell them how much planning went into their morning pastry, but come on. It's early.

Glazed and Infused's production facility is under their Fulton Market location at 813 W Fulton Market. Soon, you'll be able to see doughnut making in the upstairs finishing kitchen.