Interview: Artist Theaster Gates Discusses His New MCA Exhibit

By Jessica Mlinaric in Arts & Entertainment on May 23, 2013 6:00PM

As one of Chicago's brightest stars in the international art community, Theaster Gates' current exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art opened last weekend to great anticipation. 13th Ballad is an extension of 12 Ballads for the Huguenot House, Gates' work which was co-produced by the MCA last year for dOCUMENTA (13), an international art exhibition in Kassel, Germany.

13th Ballad examines the melding of two abandoned buildings and the accumulative affects of migration. Gates purchased the first building on Chicago's Dorchester Avenue in 2009 as part of a continuing effort to rejuvenate his South Side neighborhood. Much of the Dorchester building was dismantled and its raw materials were used to reconstruct the historic Huguenot House in Kassel for dOCUMENTA (13) by a team from Chicago and Germany who worked and lived in the space. At a media preview prior to the exhibition’s opening, Gates described his curiosity regarding similar negative energies surrounding the former crack house in Chicago and dilapidated historic relic in Germany. "I wanted to put these two buildings in conversation with each other to see what could arise."

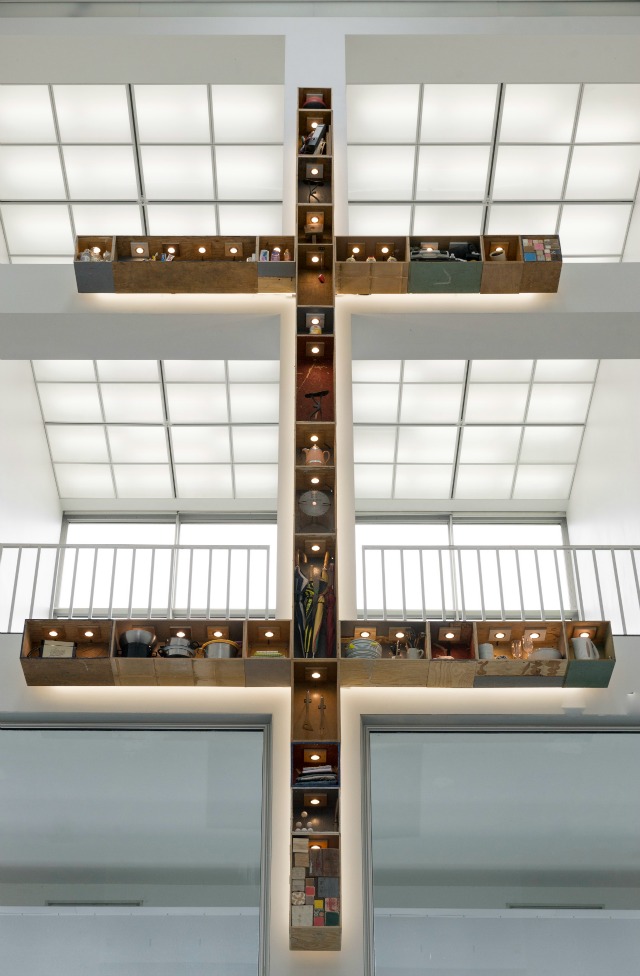

For his largest solo exhibition to date, Gates imbues two spaces at the MCA with objects and song that serve as a dialogue between the projects. In the Marjorie Blum Kovler Atrium, a large sculpture of a double-cross contains everyday items left behind at the Huguenot House. Hanging prominently above the public gathering space, the installation inspires reverence for labor at the house and its seemingly mundane instruments and recalls the religious persecution of the Huguenots. The sculpture is joined by rows of church pews which had been recently removed from the University of Chicago’s Bond Chapel to offer space for Muslim students to worship.

The installation continues in the MCA's fourth floor Turner Family Gallery featuring aesthetic and functional objects from the houses as well as preparatory drawings highlighted by video footage from the Dorchester and Kassel projects. Gates and his collaborators, the Black Monks of Mississippi ensemble, recorded a series of musical performances prior to the dismantling of the Dorchester space as well as at the Huguenot House. This combination of black spiritual music and Eastern chanting resounds through the gallery. Building upon these prior performances, a series of three collaborative performances entitled The Accumulative Affects of Migration 1-3 will be held in the atrium installation. These original compositions serve to explore the migration narrative between African Americans who settled on the South Side during the Great Migration and the forced relocation of the Huguenots from France.

Prior to the opening of 13th Ballad, which runs from May 18 - October 6, Theaster Gates spoke with Chicagoist about the restoration experience of 12 Ballads for the Huguenot House and the continued journey of these objects through 13th Ballad.

Chicagoist: How was it different to migrate everything back to Chicago as opposed to the first move of items to Huguenot House?

Theaster Gates: In many ways, what made the project exciting was that the work would go from this place that was like a “nowhere nothing” place to this other place in Germany that was like a “somewhere something” place. People would see these materials, would meet my friends who were working with me, meet these musicians who were making music, and then all of that nowhere nothingness would become something because it was in a something place. It went to this place that had the affirmation of the art world, because all eyes are on Kassel for 100 days every five years.

The work only really completes itself when it leaves the somewhere something place and goes back to the nowhere place, but it’s still something. It’s exciting that 2x4s and 2x6s, wooden lathe, plaster, and asphalt shingles, all very mundane building materials, mean something because of their participation in dOCUMENTA. They've been loaded and charged, and when they return to Chicago they return kind of victoriously. It’s really exciting to think about having these things at the MCA, but it’s also a little bit sad because it meant that after all of the work that you do to restore and make usable this building in Kassel we had to undo a lot of that work. We were able to do it with the understanding that now people in Kassel will regard that building as something special that hasn’t been special in a very long time.

How do you make things special? How do you make people want to go to a place they've never wanted to go to? Or make them go to a place they’d never go to because they thought it had certain stigmas? Now people are excited to go to the Huguenot House and people are excited to come to Dorchester to see where these materials came from, and that’s cool.

C: Now that these items have charged significance attached to them, how does being in a contemporary art museum space inform their meaning?

TG: Well it would be a shame if some of those objects didn’t end up on Dorchester permanently. What I think museums do very well is that they say to a public, “We have some stuff that’s worth looking at.” The reason artists want to have works in museums is that we want our works to be seen by as many people as possible and we want our ideas to be understood in more complicated ways.

Had the works just come back to Dorchester, I think we could have made meaning with them just fine as a site specific opportunity. The fact that the work is affirmed by the Museum of Contemporary Art I think sends continued signals that this is worth paying attention to, looking at, and understanding.

C: Can you describe the objects inside the double cross?

TG: The double cross is comprised of things that people left behind. Shampoo, toothpaste, toothbrushes, umbrellas, the glasses that we bought from the thrift store in Germany, and parts of the Huguenot House. It felt like if I was going to give a nod to this complicated relationship between power and otherness, the Catholic Church and Protestants, the leading reigning power and the others, that this house they had built was an extremely democratic space. Once we gave shape to the house and said, “Things are gonna happen here,” people wanted to be there. It didn't require a lot of arm twisting.

C: You mentioned that it was the place at dOCUMENTA where people ended up hanging out.

TG: It’s where people ended up. It was the spot. It’s really exciting to know that people want to use the house as a house and want to live there although it hasn’t been a used, occupied space in 50 or 60 years. It felt like a feat.

Those objects are a trace of the everyday things that happened there. In the form of the double cross they also have this ambition to talk about the complexities of what happens when “others” move to a place where they’re needed but not necessarily wanted. They’re needed, but maybe can live somewhere else. They’re needed temporarily and once they’re not needed anymore they want to get rid of them. I think about that story a lot when I think about skilled labor transforming places. The Huguenot story is not unlike many stories.

C: There’s always an “other.”

TG: Yes.

C: You spoke earlier about accumulation and about assembling the tools of the artist, tools of the worker, and everyday objects. What is their relationship to each other?

TG: In some ways I hoped the dOCUMENTA project could conflate those things. There was no difference between the art object and the finishing of the stairwell so that it could be code compliant with the German occupancy standards. The same team made artistic decisions and design decisions that would allow the space to be occupied appropriately. We took plaster and we patched walls, and we took plaster and put it over lathe to make paintings. Sometimes we’d place the paintings over a hole in the wall that we didn't want to plaster because the hole looked so good. It really ended up being about the ability to see the possibility and to redeem that possibility with our hands.

In many cases what was needed was not an art object as much as an intervention that could make space available so that things could happen. Something that I said over and over again was, “Let’s make space. Let’s make space.” We made space so that the MFA students in Kassel could have their exhibition there. People would come with their art objects and say, “I would just love to show my sculpture on the mantle over there.” Both Kassel and Dorchester have been about making space and that felt like the principle artistic intervention. After making space, or sometimes alongside making space, sometimes objects would appear. Discrete things that we would identify as works of art would reveal themselves.

C: You didn't necessarily set out with the intention of having everyone live and work in the space at Huguenot House. Do you have a favorite memory of that experience?

TG: The opening day when the Black Monks first performed there were a couple hundred people who couldn't get in. The room was packed and the rooms beside it were packed. We were sitting down inside getting ready to perform and there was such big hopeful energy in the room. People had great expectations of what was about to happen onstage, but they also seemed pleasured by just being present among each other in this building sitting down on these 200 year old floorboards. The Monks gave the building purpose in a very special way. I felt more like a witness to it than the instrument that devised it. I was just kind of caught up with everybody else. It was great.

C: Can you speak to the upcoming musical performances and the original material you wrote?

TG: What I realized in Kassel was that we really didn’t think a whole lot about the Huguenots We called the building the Huguenot House and knew it’s history to some extent. We met someone who grew up there; she was 86. After having some distance from Germany I thought the music in Chicago should reflect the question of duty, labor, country, and God. We identified a composer named Giacomo Meyerbeer who wrote a play called Les Huguenots in the mid 19th century and Wagner was an understudy to him. He was a Jewish cat, an outsider talking about an outsiders' experience. I liked this.

The performances started with Meyerbeer and then the great southern migrationist Muddy Waters. So I used Meyerbeer and Muddy Waters to compose a new body of music that the Black Monks of Mississippi will perform over the course of the exhibition. There will be one new work performed at each of the three performances. Sometimes these works riff on slave hymns and calls, but they’re originally composed by me and a great musical director Michael Drayton. The music is the sound of black migration lyrically reflecting on the story of the Huguenots.

C: How does living and working as an artist as opposed to full-time urban planning or full-time institutional arts planning afford you different means to communicate?

TG: I think I’m a full-time artist, a full-time urban planner, and a full-time preacher with an aspiration of no longer needing any of those titles. Rather, I’m trying to do what for some seems a very messy work or a complicated work. I feel we have to give more time and more consideration to the disparity between wealth and poverty in our country.