Interview: 'The Trials Of Muhammad Ali' Director Bill Siegel

By Chuck Sudo in Arts & Entertainment on Nov 7, 2013 5:00PM

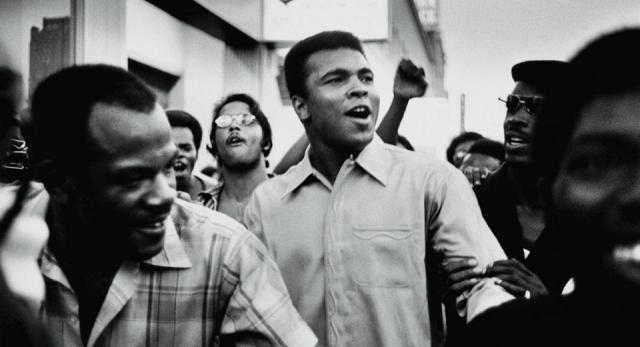

There have been scores of documentaries made on the life of Muhammad Ali but all of them overwhelmingly focus on Ali's pugilistic exploits over over his religious and social awakening in the mid-1960, in particular his joining the Nation of Islam and his conscientious objection to the Vietnam War. The latter resulted in Ali having his boxing license suspended across the country as he was entering his prime physical years and he was forced to take on a series of speaking engagements on college campuses and theaters in order to provide for his family.

It is this period of Ali's life that is the focus of The Trials of Muhammad Ali, a new documentary by Kartemquin Films that is now playing across the country. Director Bill Siegel (The Weather Underground) and his co-producer Rachel Pikelny researched the film for years, poring over thousands of hours of archival footage—some not seen in nearly 50 years—to frame Ali's growing social consciousness with his suspended boxing career in the background.

Another thing that separates the new film from previous Ali documentaries is the small number of witnesses to Ali's awakening Siegel interviews. Instead of the usual procession of celebrities sharing their memories of the Clay-Liston fight or the Thrilla in Manila, Siegel interviews the people at Ali's side such as his brother Rahman, second wife Khalilah Camacho-Ali and, in a major coup, Nation of Islam leader Louis Farrakhan.

In an interview conducted a couple weeks back, Siegel spoke with Chicagoist about the film, landing the Farrakhan interview and how Ali's strength and courage continue to inspire today.

Director Bill Siegel

BILL SIEGEL: The genesis for this film happened around 20 years ago while I was doing research for another Ali doc, Muhammad Ali - The Whole Story. I knew then that movie would focus on boxing—with substance—but would skim over the most important period of his life which was his exile. It also coincided with my own awakening about that time in Ali’s life. For example, I didn't know about the speaking engagements he did to earn a living until I started my research.

C: There have been so many documentaries made about Muhammad Ali over the years and the one that comes closest to digging deep into his spiritual awakening is Muhammad Ali: Made in Miami. Why do you feel so many directors have ignored this part of Ali’s life?

BS: I like Made in Miami. It is a decent film. Ultimately, it’s apathetic in its focus on Ali’s life in Miami away from the first Liston fight. For me, the closest anyone’s come to exploring Ali’s spiritual and social conversion was a segment produced for the Eyes on the Prize civil rights series on PBS. But it was so short. For most part that William Klein film [Float Like A Butterfly, Sting Like A Bee] is a litany of boxing stories—almost exclusively about fights. Everything sort of skips around Ali’s exile.

C: Did the large number of Ali documentaries in existence hamper your ability to raise money for producing this film? Did anyone say to you, “Why do we need another film about Muhammad Ali?”

C: And then there’s Minister Louis Farrakhan. Few of the reviews of the film I read in preparation for this interview mention Farrakhan’s reflections in the movie, yet he had a ringside seat to Ali’s indoctrination in the Nation of Islam and his recollections of Ali’s life with the church are some of the strongest in the film. How did getting the interview with Farrakhan come about?

BS: We worked on landing the interview with Farrakhan for over a year. Ultimately it was Ali’s second wife Khalilah who helped us gain access to Farrakhan. Khalilah was born into the Nation of Islam and her institutional memory of the group was what helped us through the door that day. Great things have happened every time I've been with Khalilah; she said, “don't be surprised to be in Louis' living room.”

C: What do you remember most of the interview with Farrakhan?

BS: The atmosphere in the room was intense. No matter how gracious Farrakhan was—and he was a very charming man during the interview—he was personally intimidating. We received word through his son (via Khalilah) that we had 15 minutes to set up our equipment and 20 minutes for the interview. When we got inside, Farrakhan’s folks already set up the room and had a spot picked out for us. We were grateful for that because we wound up having no time to set up. From the moment we started filming he was charged. I asked Rachel [Pikelny, Siegel’s co-producer] to sit aside and pinch me with five minutes left so I knew when to wrap up the interview. She did. Farrakhan caught it and asked, “what was that?” I explained the signal we set up and Farrakhan said, “Oh, never mind;” we wound up filming him for an hour.

BS: I don't know. For me, in terms of eyewitness strategy, there’s no one better to talk to than him. Louis Farrakhan has his polarizing qualities; he may be viewed as divisive now but he's not nearly as antagonizing as Ali was then.

C: One thing the film does a very good job of highlighting is the growing backlash against Ali because of his outspoken nature and how his conversion to Islam only intensified that.

BS: Even when he was Cassius Clay people wanted him to fail. We have the archival footage where a news reporter tells him to shut up. If you’re a reporter covering Muhammad Ali why would you want him to be quiet?

You see Jerry Lewis tell him to shut up in the film and David Susskind attack Ali on television. Ali’s conversion to Islam only added logs to the fire. His refusal to fight in Vietnam contributed to the backlash but for others he became an increasingly heroic figure.

C: Why did so many people in the media feel the need to dismiss Ali’s name change?

BS: Robert Lipsyte put it best in the film. Marion Morrison was John Wayne; Rock Hudson was a screen name; Bob Dylan took a stage name. Ali's name change was a challenge on a number of fronts. “No, I'm not gonna keep that name.” He had every right to accept that name.

C: You also note in the film that when Ali’s case reached the Supreme Court federal prosecutors painted themselves into a corner with their argument. There was more happening than simply prosecuting Ali for refusing the draft.

BS: The government wanted to dismiss Ali’s claim on a number of levels and challenge the Nation of Islam’s claim as a legitimate religious organization. Ali’s argument was, as a minister of the Nation, he qualified for conscientious objector status. Prosecutors contended he was only opposed to the Vietnam War. The asked, when it came down to letter of law, is he opposed to this war or all wars? The Supreme Court eventually ruled that Ali’s objection was for all wars.

C: The rough cuts of the film you screened at the Harold Washington Library last year were revelatory because some of the archival footage you used hadn’t been seen in nearly 50 years. What has the reaction to screenings of the completed film been from audiences?

BS: The response has been largely positive. Critically, response has been great. Audiences who can find it are well-received to the film. The hardest part now is getting people aware the film is out there. I can remember after one screening at Columbia College a student said to me, "Wow! I bet more people believe President Obama is a Muslim than Ali chose to become one."

C:Ultimately, what do you feel it was about Islam that attracted Ali?

BS: To this day, Ali as a Muslim is about changing perceptions. Captain Sam says Islam forces people to reconsider. I feel the bravest thing Ali has ever done was his appearance on the post-9/11 telethon to tell the nation, "Islam is a religion of peace." Think about what it took to say that 10 days after the attacks—it’s pretty amazing.

C: The other driving force in the film is Khalilah Camacho-Ali. Her early scenes established her as an equal to Ali who didn’t cater to his ego. Besides brokering the Farrakhan interview, how else was she integral to the film?

BS: Khalilah’s access to people who knew Ali was essential. She introduced us to Captain Sam. What meant the most for us was her passionate understanding for why the film needed to be made. She knew this part of Ali's story wasn't told as well as it should have been before and she didn't see it until it was done.

C: Is she still a member of the Nation of Islam?

BS: She’s still a Muslim but not with the Nation.

C: Malcolm X was influential in solidifying Ali’s ties to the Nation of Islam in 1964; he would leave the Nation and be assassinated a year later. Did you identify any differences between Ali's break with the Nation and Malcolm’s?

BS: Malcolm’s separation from the Nation of Islam was personal as well as spiritual. Ali just followed who the leader of the Nation was. Actually it was Farrakhan who broke from the Nation. Elijah Muhammad’s son Wafid Deen Muhammad took over and steered the church into a more orthodox version of Islam, so Farrakhan broke away and re-established the separatist and nationalist teachings of Elijah Muhammad.

BS: I wanted [Ali’s current wife] Lonnie to be in the film but she doesn't do anything in front of a camera. What she did was connect me to Hana, Ali’s daughter from his third wife Veronica.

C: Hana Ali comes across as awestruck by her father in the film.

BS: Every dad should have the love of his daughter as Ali does with Hana. She calls him the "Eighth Wonder of the World" and recognizes she had to share him with a global audience that adored him as much as she. That last piece of the film epitomizes the tension of who he belongs to.

C: How involved was Ali in the making of the film?

BS: Not very, although he and Lonnie cooperated throughout the process. My first move in the project was to get Ali's blessing. Ethically, I wanted him to know why I did this. I met with him and Lonnie at his farm in Michigan and told him my background as a filmmaker and why the film was important for me to do. He can't articulate verbally with his Parkinsons but he knew what I wanted to do. Lonnie, like Khalaila, got it and insisted it be made independently. She didn't want it whitewashed.

C: Did the Muhammad Ali Center in Louisville get involved at all?

BS: We worked closely with them throughout the process and the film screened there Oct. 5 to a standing ovation.

C: Any final words you have to say about the film?

BS: This is a film for the whole family in the spirit of 42. If people come out to see the film they're gonna be discovering a lot.

The Trials of Muhammad Ali is playing in theaters across the country; check the film's website for cities and showtimes. The film will screen in Chicago from Nov. 8 through Nov. 14 at the Music Box Theatre (3733 N. Southport Ave.), Chatham 14 Cinema (210 W. 87th St.) and ICE Lawndale 10 (3330 W. Roosevelt Rd.). Bill Siegel and Khlalilah Camacho-Ali will discuss the film at the Music Box 8 p.m. Nov. 8.; (tickets are available here), 4:45 p.m. Nov. 9 at Chatham 14 and 7 p.m. Nov. 10 at ICE Lawndale 10. The Music Box will also host a special screening 7:15 p.m. Nov. 13 with an appearance by the group Athletes United for Peace.