The 'Old Roseland': One Man's Experience During White Flight

By Ester Alegria in News on Jul 19, 2014 7:30PM

When I sit in my cozy wicker chair and look outside my window, I see an empty lot where a building once stood. City workers came out and put up a sign daring anyone to park there, lest they get towed. I see two abandoned houses to my right, and two to my left—one house on the street across from me where a guy that I dated for an entire week in my teenage years lived has been vacant for about 13 years.

The trees on my street aren’t even lush anymore. They bear scanty leaves atop their wooden bodies like aging men, not ready to let go of their glorious youth—the early years. They are, after all, the remains of the “Old Roseland.”

Growing up in the area, I never knew anything but the grittiness of the summer and the dirty grey snow of the winter. I knew that Old Fashioned Donuts on Michigan Avenue was the best. And I also knew that Dr. Bernardo Li was my entire family’s doctor, and most likely half the kids I went to school with. I knew, just as anyone else in the neighborhood knew, that if you’d gotten into a car crash, you needed to see “Solo.”

Roseland is a community that hasn’t realized it really is a community in the truest sense of the word. The people here have connections, and are willing to befriend each other if only they’d just take the time. This kind of willingness to connect is not too common in inner city neighborhoods.

But the startling sounds of gunfire can take away from amiable feelings, and push the more friendly people inside, or confine them to their porches.

Close enough to their doors so as to have a place to retreat when one gets tired of gun drama. Roseland hasn’t always been such a confusing place; scary to most—home to others.

“Roseland was the perfect community,” reminisced Roy Goebig, a retired English teacher from my alma mater, Carver Military High, and a good friend of mine. Roy lived in the Roseland area since his birth in 1963, at 103rd Street & Wentworth Avenue. “We were far enough away from downtown to be quiet and peaceful yet close enough to shopping, the lake, recreation, and the south suburbs.”

With its beginnings as a Dutch settlement in the 1840s, “de Hooge Prairie,” or the High Prairie, continued on as a predominately Caucasian inhabited area. Roseland was home to blue collar workers from all over Europe as well as their first, second, and third generational offspring. It was a tightly knit community and people made the effort to get to know who their neighbors were.

“In those days you didn’t tell people where you were from; you told them what parish you went to. We had the ‘Avenue’ a stretch between 111th and 115th on Michigan Avenue with shops, diners, record stores and other various hangouts," Goebig said. "Even Walgreen's had a soda fountain in it like on Happy Days."

"After school and weekends were the times to be seen ‘Up the Ave.’ Landmarks like the Griffith Natatorium (the Pump) 2 blocks away for year round swimming; Fernwood Park was a short bike trip away with Calumet Beach on the lake a bit further still," Goebig said.

Goebig continues.

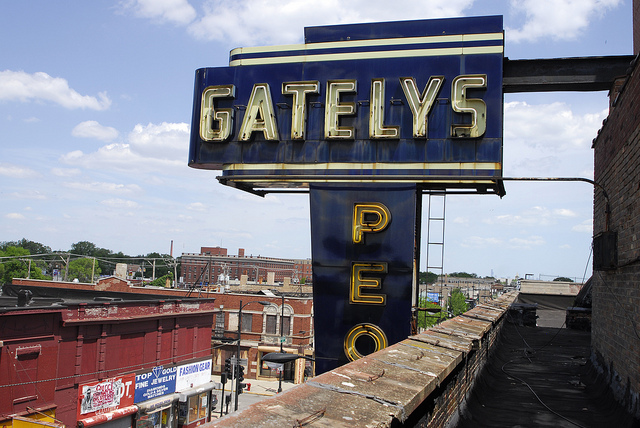

One bus took us to White Sox Park and we could walk to Gately Stadium on Cottage Grove for high school football games. We even had a ‘haunted house,’ the old Ton mansion on the northwest corner of 103rd and Princeton. As a kid we were frightened and intimidated by it, but in my teen years we broke in through the basement window, dispelled our fears, and played inside. It was later torn down and replaced with a Hi-Low grocery store.”

Looking through an online photo album marking Roseland’s “glory days,” I’m reminded of the many crumbling structures, currency exchanges, beauty supply stores, and fast food restaurants that have replaced those places of leisure.

That is the Roseland I’ve come to know so well. Today, violent cliques formed after the demolition of the Robert Taylor Homes and closure of other housing projects—futile attempts to quell gang violence near the loop, furthering gentrification.

Upon asking Roy if he had any clue as to why the “white flight” of Roseland occurred, he explained how African-Americans lived mainly near the loop. And as they slowly began to migrate south, whites moved further south. And, as expected, racial tension between some African-Americans and some of the lingering Caucasians erupted.

“[Especially] after MLK died, there was a lot of stupid violence from both sides. None of it made sense. I never understood any of it,” Roy mused.

Roy has been touched by the tension when he found himself in an interracial relationship with a young African-American woman soon after moving out on his own. He’d known not to take her out in the Roseland area for fear of backlash from the white people in the area. So they went elsewhere.

They ended up being seen by Roy’s aunt and uncle anyway. When he got home, he received a phone call from his mother. He knew she wanted to ask about his date. “Can’t you find a nice white girl to out with?” His mother asked. Ever sarcastic, Roy replied, “It could be worse mom, I could be dating a black man.” At the time that would have been quite the scandal.

I wondered if he’d gone back to visit since he’d moved away.

Of course! I'd take a drive there when Carver had football games at Gately Field. And since I’ve moved away to Indiana, I’ve visited. Most recently with my mother. She was quite afraid for our safety. But I assured her we’d be fine. We drove around to take a look at some familiar places, and to remember. Things have changed. The recent shootings haven’t helped things at all. But I still love the place. Good old Chicago. Gotta love it; just a great place to be!

Roy Goebig taught English at Carver Military High in Altgeld Gardens back when I was a teenager. His genial nature and bawdy wit was a cool and refreshing undertone to the loud hallways filled with yelling from the students. Rarely had I seen him without a smile. Sitting calmly in his wheelchair, he’d been partially paralyzed years before in a car accident.

“People would ask me if I was afraid to work there, being in a wheelchair and all. Afraid of what? Teaching at inner city schools isn't like in the movies. I remember being afraid once. That was because I saw the principal walking down the hall and I thought I was in trouble.” Goebig joked;

I asked him if teaching at Carver was sort of a way for him to go back to his neighborhood roots and give back.

“Absolutely!” Goebig said.

I graduated from Chicago State in 1972 and began my teaching career. Two years at Fenger High School. Both of my parents graduated from there in 1942 and 1945 respectively; then assigned Lucy Flower on the west side. I was there 4 years when I took advantage of an integration transfer and came to Carver. It was in the years 1977-78. The ‘new’ Carver was only a few years old then but already had a ‘bad’ reputation. However, after 4 years on ‘Westside’ I was undaunted. I felt nothing but love and respect during my 30 years there and I felt I gave back equally in return.I was, and still am, very proud of the students there and revel in the successes they have accomplished and horizons they have conquered. However, my family, immediate and extended, all worried about my well-being there, especially after my car accident. I constantly told them that their fears were groundless but they continued to worry. When I was in the hospital after my accident I occasioned to visit the school with my parents for an afternoon.

My parents were astonished at the outpouring of love and concern from the students. I believe that was the first time in my parents’ life when they were in the minority. After a moment of initial discomfort they realized that this too was a ‘family’ I belonged to and loved and was loved in return. They were amazed and often spoke of that day to other family and friends. Yet I knew there were more strides to be made in race-relations in my own family when they told people that ‘those people’ really love and respect our son. A small victory, yet a victory nonetheless!”

When I walk down Wentworth Avenue, my home, it’s hard to imagine there being more than my stepdad, the sole white man living on my block, across the street from my own apartment. Anyone who’s lived in Chicago a substantial amount of time will tell you that the city, while pleasantly diverse, is quite segregated.

There’s a neighborhood for pretty much any ethnicity you can think of. Roseland’s Dutch beginnings, Catholic past, urban present, and unsure future only add to Chicago’s rich storyline.

As sure as the Dan Ryan came through in the 1960s and changed the dynamics of the lives of hundreds of families, this city will continue to evolve. However good or bad the outcome, we are Chicagoans. If we can survive the weather, we can survive anything else that comes our way.