Daniel Woodrell Honored With The Heartland Award For Fiction

By Jaclyn Bauer in Arts & Entertainment on Nov 4, 2014 5:30PM

Daniel Woodrell, photo credit: Paul Beaty / photo for Chicago Tribune

During this year’s 25th anniversary of the Chicago Humanities Festival, the Heartland Award in fiction was given to Daniel Woodrell. The Heartland Awards “honor a novel and book of nonfiction embodying the spirit of the nation’s heartland...[it] recognize[s] words that reinforce and perpetuate the values of heartland America."

Woodrell was recognized for his 2013 novel The Maid’s Version, which details the mystery surrounding a dance hall that burned down in 1929 leaving 42 people dead. Woodrell is perhaps best known for being the author of the recently acclaimed film Winter’s Bone; however, he has been publishing since the 1980s and hold high esteem among the literary community.

In conversation with the Tribune's Rick Kogan, Woodrell delved into his personal history, his writing process and his passion for writing.

Many of Woodrell’s novels take place in the Ozarks of Missouri where he grew up, and where he and his wife, writer Katie Estill, call home. He didn’t have the most conventional education, though his parents both taught him that books were important from a young age. Woodrell dropped out of school to join the Marines in 1970. He already knew he wanted to be a writer at that point, but he wanted to accelerate his experience of the world.

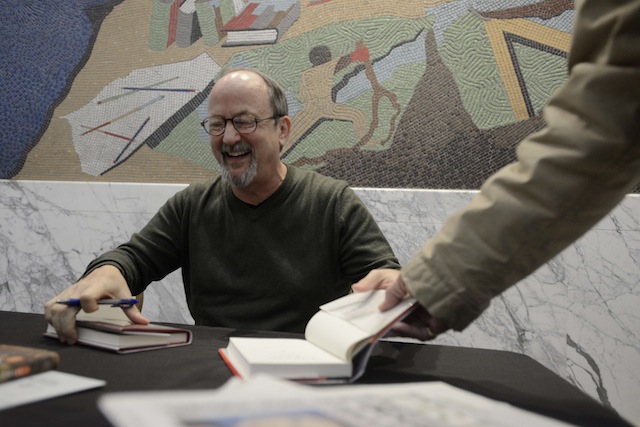

Daniel Woodrell in conversation with Rick Kogan, photo credit: Paul Beaty / photo for Chicago Tribune

After publishing his first novel Under the Bright Lights, Woodrell never had another job outside that of full-time writer. He always knew he wanted to either “sink or swim” as a writer, and even though he might not be considered successful to the degree of someone like Stephen King, Woodrell elucidated that he and his wife live comfortably enough in their small rural town. Woodrell laughed while telling the story of his neighbor who only recently discovered he was writer after conjecturing as to whether he was a drug dealer or on disability.

Woodrell is not a flashy writer by any means, he doesn’t care to write his work for the commercial market and he prides himself on pouring his whole self into his writing. When first approached about making a film of Winter’s Bone, Woodrell was immediately drawn to director Debra Granik and writer Anne Rosellini’s proposal even though he was offered other, much bigger movie deals. He was reassured that in the hands of Granik and Rosellini, his writing, message and story would be better retained.

Woodrell’s own writing method consists of him trying to sit every day; usually starting sometime around dawn and working until he feels he’s accomplished something of substance. He holds that he is not a “words” guy and never expects to get out more than 3-4 pages a day; in fact, he admitted that he is happy with a good paragraph or two. He also shared that he initially writes long-form rather than typing, saying he types faster than he thinks and gets so ahead of himself that he tends to churn out low grade work that way. He finds a few well written sentences far more valuable than a compendium of crap.

All in all, Woodrell was a humble and genuine man with a lot of great stories to tell, more of which, he suggested, are soon to come.