Bitter: A Taste Of The World's Most Dangerous Flavor

By Melissa McEwen in Food on Nov 20, 2014 8:00PM

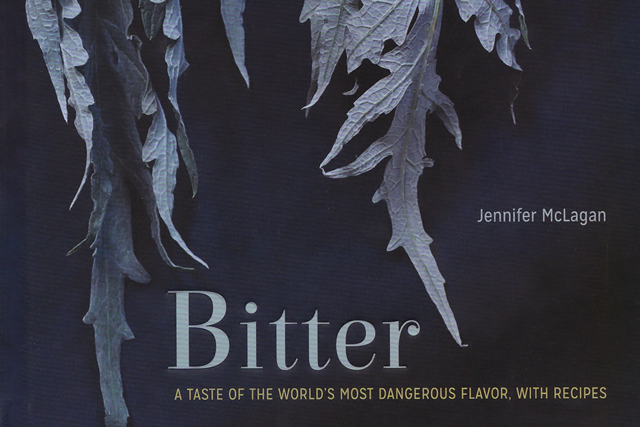

Jennifer McLagan has made a name for herself in the culinary world with her cookbooks centered on single subjects. She takes culinary subjects we often take for granted—Fat, Bones, and Odd Bits—and deftly explores every aspect of them. Her books aren’t just recipes, they are packed with interesting science and history. Her latest addition to the series is Bitter, which is subtitled “a taste of the world’s most dangerous flavor, with recipes.”

By now anyone who is serious about food and drink at least knows something about cocktail bitters and maybe even owns a book about them, such as the excellent Bitters: A Spirited History of a Classic Cure-All, with Cocktails, Recipes, and Formulas. If you are into craft beer, you are probably well-acquainted with bitter through styles like India Pale Ale. But bitter is just as important in food as it is in drinks.

Bitter is one of the most basic of all tastes and grants dishes a complexity and depth. While babies are drawn to the sweet and fatty flavors of milk, humans have to learn to appreciate bitter. We likely evolved our ability to detect it in order to communicate to our bodies about the world of plants. Bitter from a plant in small amounts can be the sign of medicinal healthy compounds. And too much can be a sign of poison.

Bitter is the defining characteristic of many vegetables, such as endive. I learned from the book that endive is much more modern and artificial than I ever imagined. It was developed in the nineteenth century in Brussels. The head gardener of the Brussels Botanical Gardens, M. Bresiers, found out that chicory, when grown indoors in a dark warm environment, grew pale leaves in a “compact tornado shape.”

One thing I love about the recipes in Bitter is that they range from simple recipes that offer a unique take on a food to more time-consuming recipes. The latter are great for when you have a lazy Saturday afternoon to devote to things like making a radicchio pie with lard pastry, which I totally wanted to make since it has prosciutto and cheese and nothing with these things can possible be less than amazing.

But being a weeknight, I opted for the grilled radicchio with creamy cheese, a genius combination that takes the hot charred leaves and mixes them with a soft cheese so it melts them perfectly. I opted for the Great American Cheese Collection’s triple cream brie, which is like if your favorite normal brie and a stick of butter had a baby together. It’s perfect for balancing against bitter flavors.

It was so good grilled I could hardly imagine that radicchio was once to me only known as the weird red stuff in mediocre bagged salad mix that I often picked out gingerly when no one was looking. It only strengthens my view that charring is the secret to great vegetables. Don’t grill it into oblivion though, it’s nice to leave some crispy red parts to contrast with the dark brown grilled parts.

Grilled Radicchio With Creamy Cheese

serves 4 as a side dish

2 heads treviso radicchio, about 7 ounces/200 g each

Olive oil

Sea salt and freshly ground black pepper

2.5 ounces/75 grams creamy cow’s milk cheese (“my choice would be a Normandy Camembert, a Pierre Robert, or a Brillat-Savarin’)

2 teaspoons balsamic vinegar

Cut the radicchio heads into quarters and drizzle with olive oil, turning to lightly coat the pieces. Season with salt and pepper.

Heat a gas grill to medium, or set a heavy cast-iron pan over medium heat. When it is hot add the radicchio and cook, turning often, until it is soft, brown in color and lightly charred, about 12 minutes. Cut the cheese into pieces.

Transfer the radicchio to a serving dish. Top with pieces of the cheese and sprinkle with the balsamic vinegar. The heat of the radicchio will melt the cheese.

Reprinted with permission from Bitter: A Taste of the World’s Most Dangerous Flavor, with Recipes by Jennifer McLagan, copyright © 2014. Published by Ten Speed Press, an imprint of Random House LLC.

Cooks notes: Make sure to adjust the level of salt based on the saltiness of the cheese. Some soft cheeses like Brillat Savarin can be really salty. We recommend you buy twice the amount of cheese needed and eat the rest before you cook this dish. For, you know, education.

For my cast iron, I heated it up at 350 F for 15 minutes to get it evenly hot before “grilling” the radicchio.

Also if you want to try something different, you can use anything else acidic in place of the balsamic such as fresh lemon juice. If you can’t find treviso radicchio, any kind of radicchio can grill well, just make sure to cut it into smaller pieces if it’s a thicker variety (kitchen shears work perfectly for this).

Weirdly, radicchio is also created by growing chicory in the dark, a technique invented by another Belgian gardener in the 1860s. Growing things in the dark prevents chlorophyll, which makes plants green, from developing in the leaves. So the color of radicchio is kind of like autumn leaves, which are such glorious colors because their chlorophyll breaks down.

Beyond common foods that impart bitter, the book also explores culinary uses for bitter plants that aren’t often used in food, such as tobacco. I’ve seen tobacco on a few tasting menus here and there, but Bitter offers home cooks the chance to impart tobacco chocolate truffles and tobacco panna cotta with the same woody and earthy flavors you get from opening a cigar box.

One of my only complaints about the book is in the print edition some of the science and history sections are white text on a muted green background, a color combination so low contrast that you may be forced to read under a bright light.

But whether to just enjoy reading or to cook from, Bitter provides an enlightening experience that will change the way you see food. Bitter might not be the most appealing sounding flavor, but it reminds eaters that not all of life is easy to enjoy, and that some of the best things in life require you to learn to love them.