Bloodshot Records Celebrates 20 Years: An Oral History Of Its Beginnings

By Katie Karpowicz in Arts & Entertainment on Nov 20, 2014 3:50PM

Rob Miller (left) and Nan Warshaw, founders of Bloodshot Records/Photo: Jacob Boll - DEMO Magazine

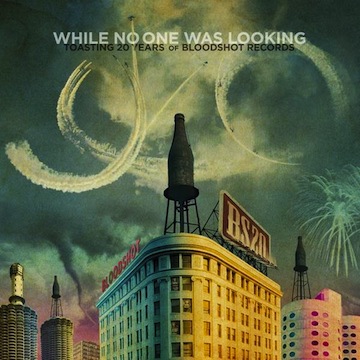

Bloodshot Records may have chosen to title its latest compilation While No One Was Looking but, after surviving twenty years in a tumultuous industry, clearly there were a few people paying attention to the local label along the way. Bloodshot's year-long celebration of its substantial anniversary comes to a close with this latest release, a collection of past Bloodshot classics covered by some of the biggest names in alternative music right now. The tracks range from perfectly fitting (Andrew Bird and Nora O'Conner covering Robbie Folks) to ambitious (Into It. Over It. covering Neko Case) to completely unexpected (Diarrhea Planet covering The Waco Brothers).

Before Bloodshot's 20th year as one of the city's best loved labels winds down, we had founders Nan Warshaw and Rob Miller reflect on its humble beginnings along with one of its earliest artists Robbie Fulks.

Before Bloodshot's 20th year as one of the city's best loved labels winds down, we had founders Nan Warshaw and Rob Miller reflect on its humble beginnings along with one of its earliest artists Robbie Fulks.

NW: Nan Warshaw, Bloodshot Records founder/owner

RM: Rob Miller, Bloodshot Records founder/owner

RF: Robbie Fulks, singer/songwriters, Bloodshot Records artist

In the summer of 1994 two punk-roots country fanatics (along with fellow founder Eric Babcock, who has since left the label) released For A Life of Sin: A Compilation of Insurgent Chicago County but the idea of operating a full-service record label had never crossed either of their minds.

NW: I was working peripherally in a variety of areas in the music business. I worked in bars and so I did book some bands. I booked friends' tours and I also DJed while I was in college on college radio. In college I played in a few bands, never well, and part of that experience, as fun as it was, was learning that my talents do not lie in the performance side.

RM: I was also a college DJ and then I worked for a concert promoter in Ann Arbor, Flint, Detroit—that whole area doing stage and production managing. I essentially learned every conceivable way that a promoter can screw a band over, which became very helpful when when it came to working at the label so I could kind of counteract that. I actually moved [from Detroit to Chicago] to get away from music and go to school. I certainly never thought about owning or running a label.

NW: I was DJing a country night at a punk rock bar called Crash Palace, later it turned into Delilah's. Rob was a regular there making requests. That's how he and I met, through our passion for country songs.

RM: I would come in and ask her for stuff that she didn't have, like The Knitters, so then I would come in the next week with the records. I finally annoyed her so much that I just started DJing every other week.

NW: I was the publicist for Killbilly and they had one record on Flying Fish Records and Eric was working there at the time. It was a local folk label. It's no longer around but was for decades.

The friends' bond eventually led to a desire to further expose the music that drove them together.

RM: In the winter of '93 or early '94, we were just hanging out at the Ten Cat or Delilah's or Lottie's just loving music and loving this underground scene that was happening all over the city with these roots-oriented bands that didn't necessarily know each other. We thought, well, what if we stitched together fifteen or twenty bands from this town that no one's paying attention to and put them all under one umbrella and see see what happens.

NW: At that point we didn't think of ourselves as a record label. We thought of ourselves as some people putting out a compilation.

With the release of A Life of Sin, Nan and Rob began to establish relationships with local artists that would far surpass a single compilation.

Robbie Fulks

Robbie Fulks

RM: As [A Life Of Sin] was being put together, we were just sitting around my house a lot listening to records and probably drinking too much. We had a Sundowners record and there was this great song called "Cigarette State." We looked at who wrote it and it said "R. Fulks." And we looked Robbie up in the phone book right then and there. That's how that happened. God bless the phone book back then. [laughs]

RF: It was definitely an accident but everything is. Everything just kind of falls into laps. Really, I was looking for somebody other than myself to put out my music for ten years so once somebody agreed to on any level I was really ecstatic.

Rob and Nan's next project was a national compilation (Hell Bent: Insurgent Country Volume 2) that attracted even more attention.

NW: We certainly put on the face of trying to look like a real label. Because [A Life of Sin] was a compilation, we were able to have a few release shows with three or four bands each around town. That allowed us to make a much bigger splash for a little record than we ever could have otherwise. It was a lot of these bands' first release so they bought copies from us to sell at their shows. That helped spread the message further. We just put the records and the CDs in stores on consignment and when they sold out, we went back and restocked them. We sold out of that first 1,000 records and made that money back so then we said, "Wow. What should we do next?"

RM: We were doing all of this from Nan's kitchen table in her apartment in Wrigleyville. Everyone on the compilation was just so glad that someone was going to put out their music that there was no expectation of a career. It was just people getting to document what they were doing at that time. We quickly started hearing from writers and bands all over the country that there were these small scenes happening in their towns as well. We had kind of tapped into something that was kind of percolating underneath the surface of the whole alternative rock mainstream-itization that was going on. That quickly led us to our next compilation which had the Old 97's on it and The Bottle Rockets and bands from all over the country.

RF: In the beginning we did a lot of package shows. You'd show up and there would be five or six other Bloodshot acts playing with you at the Empty Bottle or wherever it was. We'd get to know [these other artists] just talking in these little tight places with no dressing rooms. We were just kind of thrown in the same little cesspool together. That was part of the camaraderie.

NW: Hell Bent was a national compilation, but at the time we couldn't call it "country" because country was a bad word, certainly in college radio.

RM: And it still is.

NW: If we would have used that word, we never would have even gotten the right people to consider [the compilation]. So we came up with the term "insurgent country" which we've spent the last 15 years trying to live down. There was no critical language around for what we were doing at the time. The term "alt country" came out during those early years but that didn't necessarily fit what we thought we were doing or the people who were defining it were defining it differently than the music that interested us.

It wasn't long before the partners began furthering their talented roster, sometimes without even intentionally looking.

NW: A few years in, our first paid employee was a part-time publicist that we hired. It was Kelly Hogan. We weren't paying ourselves anything at that time. It began slowly then, we began to feel an obligation to our employee and the artists we were working with. Some of these artists were putting their careers in our hands so that's when we had to take it all more seriously.

RM: Kelly [Hogan] moved to Chicago for the same reason I did: to get away from music. I actually found out several months after she started working for us that I had reviewed her first solo record [in a magazine] that had come out a few years before that. I heard that she could sing and then we had one of our bands opening for John Wesley Harding. She went up and sang with them. I fired her that night so that she could go back to singing.

These types of charming occurrences would eventually lead Bloodshot Records to its fifth, 10th and now 20th anniversaries. The label's style may have expanded in some ways. It may have adapted to the current digital age industry in others. However, Warshaw, Miller and Bloodshot's artists have remained as tight-knit and full of class as they ever have been.

RM: I would love to say there was a grand plan or even a minor plan but the plan was to somehow figure out how to press up 1,000 records and get into some shows for free and have something to think about while I was dry walling houses in Rogers Park. Everything that happened after the A Life Of Sin compilation came out was unexpected and just kept organically driving us forward.

RF: At this point, I'm kind of an old guy and I know Rob and Nan very well and I think they're much stronger than they were in the mid-90s so I'm kind of happier at this point being with Bloodshot then I was then. Just their longevity indicates that they're smart business people.

NW: What drives us is still the great music. We work with artists that are still inspiring us by turning in a new album and blowing us away with their development. Or it's the live show where there's a solo or a new way that they've reconstructed an old song or some brilliant harmony that just puts a dumb smile on my face.