'Mama Koko And The Hundred Gunmen' Reveals The Horrors In Congo

By Jaclyn Bauer in Arts & Entertainment on Jan 13, 2015 10:35PM

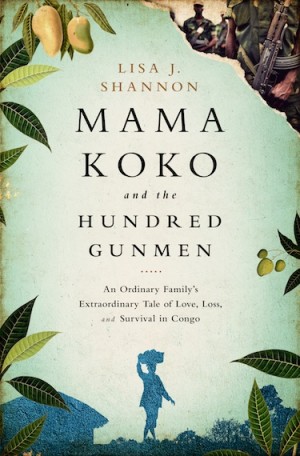

Mama Koko and The Hundred Gunmen: An Ordinary Family’s Extraordinary Tale of Love, Loss, and Survival in Congo is a story based on human right’s activist Lisa J. Shannon’s 2010 trip to Dungu, in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The book details the violence and despair that the Congolese people have been enduring since (and before) Joseph Kony’s establishment of the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) in the late 1980s.

Mama Koko and The Hundred Gunmen: An Ordinary Family’s Extraordinary Tale of Love, Loss, and Survival in Congo is a story based on human right’s activist Lisa J. Shannon’s 2010 trip to Dungu, in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The book details the violence and despair that the Congolese people have been enduring since (and before) Joseph Kony’s establishment of the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) in the late 1980s.

The book initially focuses on Shannon’s friend Francisca, a middle aged native Congolese woman working as a cheese steward in Portland, Oregon. Francisca receives a call from a friend telling her that the LRA has attacked the Oriental Province of Congo where her hometown Dungu is located. After a year of terrible news concerning the death and maiming of many of Francisca’s family members, Shannon suggests a trip to Congo with her friend. Shannon hoped that by documenting the suffering of Francisca’s family and friends, she might raise awareness about the issues in Congo and gain support from the U.S and the U.N.

The two set out on their adventure together. Francisca says good-bye to her American husband and her children in Portland and heads with Shannon to see her own mother, Mama Koko, and the rest of her extended family. Throughout their time with Francisca’s family, the two women are exposed to not only stories of violence and death, but they sit at the edge of it themselves, always on the verge of direct contact with the LRA.

Amidst interviews and video recordings, Shannon provides periodic glimpses into the past of Francisca and other members of her family. By virtue of these stories, the reader develops an even deeper connection to Mama Koko and the rest of the family. Each member of the family is so eloquently characterized that their names could be removed from the novel and the reader would still be able to tell them apart.

The only distracting element of Shannon’s book is her vacillation between her own feelings and Francisca’s. It’s as if Shannon is a first person narrator with a god-like omniscience, but this detracts from the credibility of emotions and thoughts that she attributes to other characters, especially since we know the story is based on true people and events. Shannon seems to be aware of this inconsistency, and notes in her appendices that any statement made concerning Francisca’s—or other characters’—feelings, emotions or pasts were approved by the people depicted.

One of the most valuable elements of the story is the Congolese history that is detailed at the end of the book. Not only does this brief but insightful history provide a backdrop for the rest of the story, it more fully ingrains the veracity of the issues in Congo. The fact “that during the LRA’s twenty years in Uganda more than 20,000 children were abducted and nearly 2 million people were displaced” puts a stronger emphasis on the fear and despair described by Shannon. This statistic doesn’t even take into account that “in one year alone more than 400,000 women and girls were raped in Congo during the LRA’s massacres.

An absolute must-read, Mama Koko and the Hundred Gunmen will be released by Perseus Books Group on Feb. 3. To tide you over until then, you can pick up Shannon’s winner of the 2010 Independent Publishers Association Gold Award for Best Book in Current Events/Foreign Affairs, A Thousand Sisters: My Journey into the Worst Place on Earth to Be a Woman, at your local bookstore.