The 13 Best Chicago-Centric Books

By Staff in Arts & Entertainment on Mar 4, 2015 9:00PM

From newspaper columnists to essayists, historians to comic book artists, fiction writers to poets and everything in between, Chicago has a literary tradition as rich and storied as any city's, containing arguably some of the best authors the nation has produced.

Chicago has also served as an inspiration and setting for scores of classic books by writers both homegrown, adopted or those who have never set foot within the city limits. This week, we look at the novels we feel capture Chicago in prose. It's a daunting challenge; the syllabus could conceivably be endless.

Consider these 13 books a starting point for a better understanding of Chicago's past, present and future.

The Man with the Golden Arm by Nelson Algren

The Man with the Golden Arm by Nelson Algren

Nelson Algren’s gritty noir narratives highlight both the underbelly and the provocative beauty of Chicago. The Man with the Golden Arm is a story of addiction set on the streets and throughout the bowels of the city where a man battles an addiction to morphine after returning from the war. He writes, “So far to fall, so cold all the way, so steep and dark between those morphine-colored walls.” The cold and the depth in this line, its sentiment and the writing pulsing throughout the book possesses a gloomy intrigue with Algren’s command of language. It is perfectly suited to the urban experience with his superb characterization and his incredible gift in making a reader feel a part of the landscape he creates. — Carrie McGath

Hairstyles of the Damned by Joe Meno

It’s little surprise that as bored Midwestern youth, obsessed with music and desperately wanting to leave the cornfields of my childhood for a big city, I gravitated towards Joe Meno’s well known novel, Hairstyles of the Damned. Hell, the cover of the book had a girl with pink hair (a color I begged my Mom to let me dye my own tresses, to no avail) wearing headphones on it; I was ready to fork over some cash based on that factor alone. But it was the tale of aimless youth, the sense of wanting more but not always knowing how or why you felt the way you did, that kept my nose deep in its pages. Set in the ‘90s on Chicago’s South Side, protagonist Brian is a misfit punk pining for love at a Catholic high school where he doesn’t belong. For any teen stuck in a place that doesn’t feel remotely like home (which I was at the time), Brian is an easy character to relate with. It didn’t hurt that we shared much of the same music taste and his object of affection reminded me in many ways of myself at that age. It’s a tale that many a wistful youth can relate to, and set in a city many teens pine to be a part of instead of the suburban sprawl they are stuck in for the time being.

Meno doesn’t shy away from some of the mores serious issues that have plagued our city for decades as well, specifically the racial divide that can be felt in many a neighborhood across our city. The story explores both the simple and complex all through a teenage scope, which leads to a book that reads more like a conversation at times, at points communicating in mixtapes more than words. Ah, the struggles of youth. — Lisa White

Devil in the White City by Erik Larson

I was probably among the last to read Devil in the White City, finally tackling the book during a recent beach vacation. Erik Larson intertwines two true Chicago stories—the planning and building of the 1893 World's Fair lead by Daniel Burnham and that of charming con man/serial killer H.H. Holmes, who used the burgeoning city and the World's Fair to supply himself with countless victims while remaining under the radar of local authorities. Larson recounts the tales with novel-like suspense, as the mad doctor plans and plots his dark schemes from his building in Englewood, while the city's leaders face setbacks and successes in their attempt to execute their epic White City a couple miles to the east. The parallel stories combine to show a city that was growing by leaps and bounds, while trying to shake its backwater reputation and claim its place among the world's great cities. As a lover of history and architecture, I relished the details about winning the bid to host the World's Columbian Exhibition, rounding out a team of benefactors and architects to execute the grandiose plans and the descriptions of the marvelous fair. As a fan of CSI and Law & Order marathons, I loved the gruesome crime story surrounding the first American serial killer. — Benjy Lipsman

Native Son by Richard Wright

Richard Wright’s classic novel follows the story of 20-year-old Bigger Thomas, an African American living in desolate poverty on the south side of Chicago. In his portrait of the criminal, Wright demonstrates how Bigger’s place at the bottom of the socioeconomic ladder of the 1930s determined his illicit lifestyle, which evolves with desperation from petty theft to a cold-blooded murder. The novel is organized into three parts, entitled "Fear," "Flight" and "Fate." It follows Bigger as he ultimately takes the life of a young white woman after a night out with her and her boyfriend, up through his trial. It's a long book, in which the gripping, fast-paced action of the first half gives way to the much slower reality of criminal trial and reflection. However, Wright’s beautiful prose and his tireless exploration of the gray areas within the problem of evil, as well as the relationship between human behavior and one's sociopolitical environment, make Native Son a must-read in an era where racial violence has not ceased to be the major issue plaguing Chicago's social landscape. — Erika Kubick

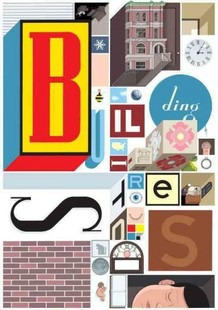

Building Stories by Chris Ware

Building Stories by Chris Ware

Building Stories is often categorized as a graphic novel, but I feel that term doesn’t do Chris Ware’s innovative masterpiece justice. Released in 2012, the boxed collection of stories is a rewarding undertaking for any reader. Presented as a board game-sized set comprised of 14 different printed pieces ranging from comic books to hard covered booklets and single-page posters, it tells the story of the inhabitants of a three-flat brownstone in Chicago. The stories of each floor’s tenants are depicted, from the elderly landlady on the first floor, to the married couple on the second who have fallen out of love, to the protagonist florist on the third floor who struggles to find happiness in her domestic lifestyle. Each floor and set of stories is drawn and written with such heartfelt realism it would be difficult for many to not identify with at least one of the character’s experiences with aging, grief, loss and doubt. And while these troubling themes carry over from story to story, what makes this collection truly special is Ware’s unique ability to weave brief moments of hope and happiness in the mundane activities that make up adulthood.

Even the novel’s format is worthy of praise. In a time where we’re accustomed to reading most, if not all, of our stories on computer, phone and tablet screens, Building Stories’ medium forces readers to pick up, thumb through and take in each piece of the story out of the box in whatever order they’d like, making each reader’s experience with the story uniquely intimate. — Gina Provenzano

Sister Carrie by Theodore Dreiser

A lot of us have been Carrie Meeber. Sure, we haven’t actually slept our way to becoming beautiful actresses, but we’ve come to Chicago from some pastoral hinterland seeking excitement. Once here, our very lack of sophistication is what seems to have invited it and years later we’ve got some stories to tell. The fact that this story still feels fresh in novel form more than a century later speaks to the depth of Dreiser’s craft, written in the realist vein of Flaubert, as well as the power of the archetypal plot itself. This isn’t The Jungle, but Carrie’s early work in a Chicago shoe factory evokes the abysmal working conditions of the time, to the point that you’re actually pretty happy for her once she agrees to become a kept woman then starts sleeping with the friend of her benefactor. Complications inevitably ensue that today only make sense given our comfort with moral indeterminacy, but at the time this was still strong stuff. All the more reason to dust it off the shelf. — Melissa Wiley

The Adventures of Augie March by Saul Bellow

"I am an American, Chicago born - Chicago, that somber city - and go at things as I have taught myself, free-style, and will make the record in my own way."

That first line from Saul Bellow’s third novel heralded an artistic breakthrough. Bellow found his true voice and let it ring from street corners and rooftops the rest of his life in this tale of a Chicago man of modest means (liberally based on Bellow himself) and the formative events in his life that owed as much to happenstance as plan. As conceived by Bellow, Augie March came to epitomize Chicago toughness and a by-the-bootstraps work ethic. March lived hard, loved harder and rarely strayed from his moral compass. Bellow penning the book as a picaresque novel wound up influencing his peers, authors who followed in his footsteps and screenwriters for generations to come. — Chuck Sudo

The Mandarins by Simone de Beauvoir

The Mandarins by Simone de Beauvoir

You don’t have to be an existentialist to love The Mandarins, but it helps. Nothing matters to this storied intellectual circle—based less than loosely on Albert Camus, Jean-Paul Sartre, Nelson Algren and Simone de Beauvoir herself—more than culling meaning from ideas. When you realize they’re living in the fallout of the second World War, you also understand if the characters’ political philosophy in particular carries some apocalyptic baggage. And because they’re human, not to mention French, love and sex get wondrously in the way.

For those familiar with the famous Beauvoir-Algren affair, the fact that much of the action shifts from Paris to Chicago feels only natural. To see the city through Beauvoir’s lapidary vision feels akin to putting on a pair of old socks from a long dead relative; you can still smell the person just after waking. Considering the distance between the two cities and the fact that Anne Dubreuilh, Beauvoir’s voice box, was married to Sartre’s fictionalized equivalent, this attraction is inconvenient to say the least, and Chicago sparkles then loses its luster as the affair devolves. Algren reportedly expressed outrage at her candor regarding their most intimate moments once he read the English translation. All these years later, readers can’t help but disagree.— Melissa Wiley

Pimp: The Story of My Life by Iceberg Slim

With a title like Pimp, one might expect the story to be about only money, clothes and vice. While those three aspects are important, they aren’t the whole story. Taking place in Chicago during the '40s, and '50s (with stops in Milwaukee and Rockford), Slim’s autobiographical novel delves into more than just the cash and flash that is commonly associated with pimping. It’s a story about race, misogyny and loneliness. This isn’t Slim going on a victory lap, celebrating his time being the biggest pimp in the Second City. Instead, he’s giving an insider look into the making of a pimp—his desires, his drive and his need to separate himself from human emotion in order to become successful. The Cadillacs, fine clothes and beautiful women a pimp surrounds himself with are only there to hide the emptiness he feels in not being able to trust or love anyone. His book serves as a warning, showing us that while the life is good for a while, it doesn’t last. Jail, drug addiction or death are a pimp’s only options in the end and they come sooner than you think. Though the book has its gloom, it’s also full of funny moments and passages where you can only say, “My goodness,” but in a good way. Written in the first person, the book is told plainly, honestly and with striking imagery. Some of it is violent, some poetic and some sexual. Even though the book was published in 1967, it still holds up and remains relevant in the realms of literature and hip hop. Rappers such as Ice Cube, Ice-T and Snoop Dogg cite the man and his book as an influence for their careers. — Ben Kramer

The Jungle by Upton Sinclair

The Jungle takes everything that could have possibly gone wrong for an immigrant family in late 19th and early 20th century America and wraps those onerous incidents up in a tiny, crowded box with a corrupt capitalist bow on top. Skeevy realtors trick the Rudkus family into buying a dilapidated home they will never be able to afford; Jurgis breaks a limb at the factory, forcing weeks of recuperation (and thus no pay); his wife Ona works for an overlord who sexually assaults her; their youngest son drowns on the front stoop during a muddy flood of river and sewer. It is a heart-wrenching story written by muckraker Upton Sinclair, who himself spent time working under guise of general laborer in Chicago’s stockyards and meatpacking factories. Like any dependable muckraking story, Sinclair’s tale of promise turned depressing defeat enlightened and polarized readers. As Sinclair famously declared, “I aimed at the public’s heart, and by accident I hit it in the stomach.” President Theodore Roosevelt held disdain for the writer’s socialist affections (in the end, Jurgis has nothing but finds a flickering light in the socialist circle), but yet the novel disgusted the government enough to send investigators to our fine city which led to the eventual passing of the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 and the creation of what is now the Food and Drug Administration. Just over a decade passed before Chicago’s monumental success in the 1893 World’s Fair dissolved into the unfavorable portrait of rat poop in our sausages and greedy men destroying families’ meager hope of a more fulfilling life. Would Sinclair be impressed or distressed by our meatpacking district today? It might be better that he never know. — Kristine Sherred

The Time Traveler’s Wife by Audrey Niffenegger

The Time Traveler’s Wife is a unique love story set in Chicago that spans a lifetime, just not in chronological order. Henry, diagnosed with Chrono-Displacement Disorder, spontaneously travels through time without warning to himself or the people around him. This affliction would no doubt make getting close to anyone difficult, but he finds a soulmate and wife in Clare, a “normal” woman who ages in real time. This novel, written by Audrey Niffenegger, chronicles their adventures and trials as a couple at all different ages, and combinations of ages, from Clare meeting her future husband as a child, to an older version of Henry popping up at his very own wedding. Niffenegger succeeds in making this fantastic scenario believable and all in our very own backyard. She sets her scenes in spots that readers intimately familiar with the city would know like the stacks of the Newberry Library, an underground parking lot in Millennium Park, the alley next to the Vic and even Opart Thai. This wonderfully written story is a compelling read, though, whether you’re a local or not.— Michelle Meywes

Division Street: America by Studs Terkel

Division Street: America by Studs Terkel

Studs Terkel’s true gift was his ability to coax compelling stories from ordinary people and present them to a captive audience. His 1967 oral history on the lives of everyday Chicagoans set in place the successful template that would culminate in winning a Pulitzer Prize for The Good War. For people looking for a glimpse of the Chicago of a half-century ago, Division Street still resonates today. People like the streetwise Kid Pharaoh, high school dropouts Lily Powell and Jimmy White, new arrivals to Chicago in Eva Barnes and George Drossos and steelworker Jesus Lopez are fully formed, three-dimensional characters in Studs’ hands and are proof that the struggles of old still affect those of us in the modern day. Getting people to talk was Studs Terkel’s life’s work; turning those conversations into books was a bonus. — Chuck Sudo

Bridges of Memory by Timuel D. Black Jr.

Studs Terkel wasn’t the only Chicagoan who had a gift for oral history. The still-alive Dr. Black was Terkel’s equal as an oral historian, storyteller and activist. This two-volume collection charts the influx of African Americans to Chicago from the South during the Great Migration with as much compelling narrative as Terkel coaxed out of his subjects. Black’s books capture the zeitgeist of the Golden Age of Bronzeville and its subsequent decay and is a must for the personal libraries of people interested in Chicago history, African American history, civil rights and amazing storytelling. — Chuck Sudo