'Sentenced: Architecture and Human Rights' Opens Thursday

By aaroncynic in News on May 6, 2015 9:15PM

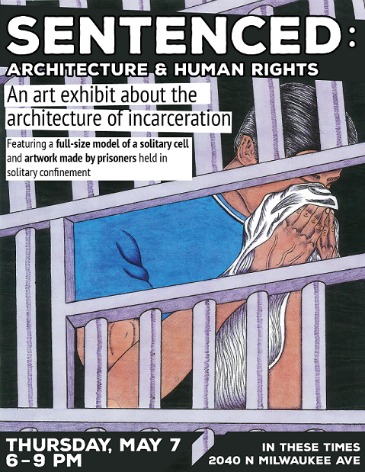

Sentenced: Architecture and Human Rights, an exhibit on solitary confinement in United States prisons, opens this Thursday at Art In These Times. A collaborative effort between Architects/Designers/Planners for Social Responsibility (ADPSR) and Uptown People’s Law Center (UPLC), the exhibit aims to show the conditions of solitary confinement, the damage it does on prisoners and to “bring voices of imprisoned people into the dialogue of the struggle to end cruel, inhuman and degrading punishment in the United States.”

Sentenced: Architecture and Human Rights, an exhibit on solitary confinement in United States prisons, opens this Thursday at Art In These Times. A collaborative effort between Architects/Designers/Planners for Social Responsibility (ADPSR) and Uptown People’s Law Center (UPLC), the exhibit aims to show the conditions of solitary confinement, the damage it does on prisoners and to “bring voices of imprisoned people into the dialogue of the struggle to end cruel, inhuman and degrading punishment in the United States.”

In 2012, ADPSR petitioned the American Institute of Architects to change its code of ethics to ban the design of both solitary confinement cells and execution chambers. In 2014, the AIA rejected the petition. Shortly after, ADPSR sent out a national call for submissions from people currently held in solitary confinement in United States prisons, which is estimated to be somewhere around 80,000. The exhibit is a collection of submissions of drawings by prisoners of their cells, as well as their experiences inside, along with art submitted to the UPLC, an organization dedicated to fighting for better conditions in Illinois prisons.

“Their work communicates both the devastation and degradation that these spaces inflict upon inhabitants as well as the resilience of these people despite abhorrent conditions,” said Lisbet Portman,” curator of the exhibit. “This is a way of bringing the people inside into that conversation— highlighting the role that designers play by asking the men themselves to design their spaces of confinement.”

The typical size of a solitary cell is smaller than an average bathroom— 4.5 x 10 feet on the small end and 7 x 10 on the large. Though it can be hard to calculate the amount of time many prisoners spend in solitary, the average sentence in Illinois is roughly 60 days. Inmates however, can end up spending a much longer time in isolation, according to Alan Mills, Executive Director of the UPLC. “You may get several sentences piled on top of each other and end up there for years,” said Mills. “There are definitely people in the state of Illinois who have been in solitary for well over a decade— some over 20 years.”

Though conditions vary from state to state, solitary confinement, also referred to as isolation, segregation, or “the hole,” usually means an inmate is confined to a cell for 23 hours a day with no “meaningful human contact” with the world outside their cell. In some cases, there can be two inmates in the same cell. Sometimes, prisons will also stack the one hour of time outside isolation for an inmate into a single day, but that time can get cancelled due to inclement weather or security concerns. “There are definitely people who spend weeks on end without leaving— just inside a box,” said Mills. “No meals, no jobs, no education or religious services. None of that exists when you’re in solitary. Everything is brought to your cell.”

The prevailing perception that solitary confinement is reserved for the “worst of the worst” of prisoners, nearly any infraction can get an inmate time in the hole. “Anything from rolling your eyes at someone to walking out of the dining hall with an extra cookie,” can get a person time in isolation, according to Mills. Many times, prisons also use the practice as a way of isolating mentally ill prisoners. According to the National Alliance on Mental Illness, 8 - 19 percent of prisoners have psychiatric disorders that “result in significant functional disabilities” and 45 percent of residents of Supermax prisons, the highest level of security in the country which make up nearly 1/3rd of the 80,000 inmates in solitary, have a “serious mental illness.”

Numerous organizations and human rights groups, including Amnesty International, the United Nations and Human Rights Watch have all condemned the practice, with many classifying prolonged solitary confinement as torture. Studies show that significant psychological damage occurs from isolation in just 15 days.

Portman said that the correspondence with inmates to the call for submissions tended to be “incredibly looping.” “The amount of stimuli the men receive in their spaces is limited,” she said. “They don’t have a lot to talk about except for their most immediate experience. A lot of them— you’d be shocked by how explicit and detailed their renders are because that is their world.”

In addition to the correspondence and rendering from inmates, Sentenced, which will run through the month on a mostly appointment basis, will also feature rarely seen designs for execution chambers as well as a full size model of a solitary cell. Opening night will also feature remarks from the organizers and one of the artists, who has since been released from prison.

Portman says she hopes this will amplify both the stories of those who’ve been stuck in solitary as well as the work being done to make conditions better for prisoners:

“Most people don’t realize what we’re doing in prisons in the U.S. so we don’t act on it. We can’t believe our own government would inflict such cruel and inhumane punishment for what are sometimes petty crimes. Prisons are designed to be out of sight and out of mind, both in structure and in placement. This is a way of turning that on its head and making highly visible what’s been tucked away. These stories help to make real and bring the human element to a much more devastating problem.”

Doors will open at Art In These Times (2040 N. Milwaukee Ave) for Sentenced: Architecture and Human Rights at 6:00 p.m. on Thursday May 7. For further information and viewing times call the Uptown People's Law Center at 773-769-1411.