Wyndham Wallace Takes Us Inside The Very Special World of Lee Hazlewood

By Rob Christopher in Arts & Entertainment on Jul 10, 2015 4:43PM

In 1999 Wyndham Wallace was a twenty-something music promoter and PR rep in London when, through a series of events, he was introduced to iconoclast music genius Lee Hazlewood. He eventually became Hazlewood's de facto European manager, overseeing re-releases and new releases, and even helped secure a show at Royal Festival Hall in 1999 for the 75-year-old's London solo debut. And, before Hazlewood's death in 2007, he also became a friend.

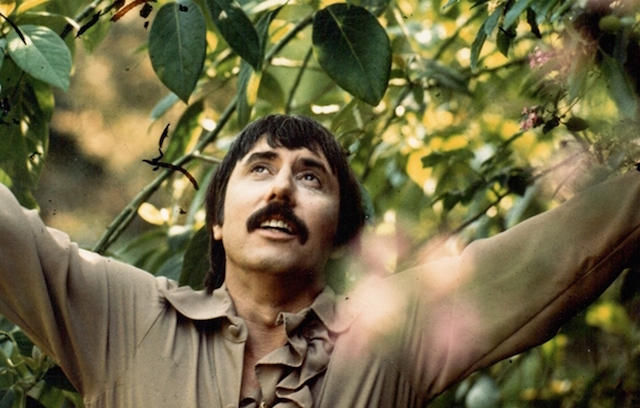

But first, who is Lee Hazlewood? If you've ever wondered about that guy with the mustache in the front window of Reckless Records, you've asked this question.

Merry Christmas and Happy Holidays!!!!! From Lee Hazlewood, Nicki Minaj & Reckless Records!!

Posted by Reckless Records on Thursday, December 11, 2014

A veteran producer and behind-the-scenes musical innovator, Lee Hazlewood first gained notoriety when the limitless twang of his recording of Duane Eddy's "Rebel Rouser" (which Hazlewood achieved by placing Eddy's guitar at one end of a grain silo) perked up ears in 1958. Later he was yanked even further out of the shadows when a song he wrote for Nancy Sinatra exploded on the charts in 1966. It was a little tune called "These Boots Are Made For Walkin'."

Several more hits followed him over the next few years, including the classic duet album Nancy & Lee. But Hazlewood never particularly sought, or was very comfortable with, being in the limelight, and by the early '70s he'd moved to Scandinavia. There he recorded a series of highly eccentric and occasionally brilliant albums that slowly achieved mega-cult status, with original copies fetching three-digit prices. Before his death he finally began to receive some long overdue recognition. And recently, thanks to Light in the Attic's invaluable work, much of his best work is finally available again.

So how and why did a cranky singer-songwriter past his prime befriend a young Brit like Wyndham Wallace? That's what the new book Lee, Myself & I: Inside the Very Special World of Lee Hazlewood is all about. It's a biography/memoir that not only paints a vivid picture of Hazlewood's life but also unflinchingly examines the often awkward reality of going from adoring fan to employee to confidant. We interviewed Wallace by email recently about the writing of the book, how he got to know Lee, and which of his recordings he likes the most.

CHICAGOIST: What gave you the idea to actually sit down and write a book about Lee? And how did Lee's family and friends react when they found out you were writing the book?

WYNDHAM WALLACE: I’ve joked with friends a few times that I moved to Berlin in 2004 to grow a beard and write a book. It took ten years, but one out of two ain’t bad. In all seriousness, though, the decision to write a book was a very gradual one indeed. Ever since I’d moved to Berlin, I’d sat down after I’d enjoyed notable experiences and written stories about those events which I then shared with a few friends. I’d done that on a couple of occasions after spending time with Lee, most notably after his two ‘last' birthdays, and in fact Lee had read and apparently enjoyed at least one of these accounts, which I later used, in an edited form, in the book.

When I was approached by a publisher in 2013 - one who’d read various pieces I’d written about my personal relationship with music for a website called The Quietus - about writing a book, it occurred to me that it was time I shared the remarkable eight years I’d spent getting to know Lee with other people, especially since there wasn’t a biography available. I’d toyed with the idea before, and Lee used sometimes to tell me stories and then say “And don’t put that in your damned book”, but I guess if there was a real spark it was that publisher's approach. They didn’t ask for a book about Lee, but I realized I had all these memories, and some incredibly valuable biographical material, and it would be a great shame if I didn’t do something about that.

In the end, I didn’t work with that publisher, and that’s probably a good thing - they no longer exist! But I owe them gratitude for suggesting I might be capable of writing a book, and finally lighting the fire I needed to fulfil the ambition I’d had when I moved to Berlin.

As for how Lee’s family and friends reacted, the truth is I didn’t really tell anyone apart from Lee’s wife, and even then I chose not to share any great details of what I was working on. After I'd first told her, I said that I didn’t want to discuss it again at any point until it was done, and she respected that. It was very important to me that I told the story of our friendship the way I remembered it. I didn’t want to risk the possibility that someone might want to make suggestions about what I should or shouldn’t include. I wanted to tell a very intimate story, one that could also provide a platform for an unusual biography, and I didn’t want it - or me - to be influenced in any way by others who were around, but who may have interpreted events differently to me. The book, as the title suggests, was meant to be about Lee and me. I dug my heels in about that, and I didn’t tell the family about the book until I was certain it was finished. And, in truth, I’m still somewhat in the dark about what any of them think about it. I hope that they can see it was written with great love for Lee, but I would also understand if they felt I’d invaded his privacy somewhat.

"Lee, Myself & I: Inside the Very Special World of Lee Hazlewood" is published by Jawbone Press

WW: That, too, was a gradual process, and I really don’t know when that point would have come. I definitely think, however, that, even by the second time we met, there was a sense that perhaps we were at least kindred spirits of a sort. To this day, it remains a mystery to me why he took me under his wing the way he did, and certainly why so soon, but I know that when he visited London for that second meeting, he seemed to enjoy having someone to share his stories with, and I think he appreciated the fact that I showed him respect but didn’t kiss his arse. Maybe, too, we both felt like outsiders in the music industry. So I didn’t realise it at the time, but perhaps subconsciously I knew at least that we got on well by that stage.

Then again, when he came to London a month or two later to perform at the Royal Festival Hall - a show I’d set up - I think he realized that I was efficient, dependable, and that I also loved hanging out over a few drinks as much as he did. In other words, I think that might have been when I won his trust. Certainly, when he decided to proceed with a show a couple of weeks later in Sweden, he demanded that the organizers pay for me to be there, even though he could have dealt with stuff himself if he’d wanted to. So that was probably also a sign that he thought of me as more than just his UK publicist. But what he thought of me as was unclear - at the time I didn’t like to make any assumptions at all. After all, he was THE Lee Hazlewood, and I was just Wyndham Wallace: the idea that I could be a great deal more to this legend than just a business associate was pretty much unthinkable until the last year or two of his life.

C: Did Lee talk much about his songwriting process, or give any tips about it? Did he prefer to write songs when he was by himself and arrive at the studio with everything mapped out, or did he like to improvise?

WW: Honestly, I have little idea. I was never really party to his creative process. I didn’t even know he was working on Cake Or Death, his final album, until he was quite some way into it. That, in all fairness, was because I was in the middle of some pretty difficult things in my personal life around the same time - things I allude to in the book - but he didn’t really talk to me about the way he worked. I only visited the recording studio with him twice, I think, and both times it was for collaborations that other people had prompted, and not for songs he wrote.

Having said that, I suspect he was always pretty clear in his head about how he wanted to make records, and yet he was also capable of being spontaneous: with Cake Or Death, when he discovered that the label of a French singer with whom he originally recorded ‘Nothing’ wanted silly money to allow her to appear, he just junked her vocal and immediately invited a German singer he’d met the day before to replace her. I doubt that was out of character: he could be pretty impulsive. So, the more I think about it, the more I think he was very clear about he wanted - and certainly he had a reputation for being very, very tough in the studio - but when he wanted to break his rules he was far from afraid of doing so, as long as it was his decision.

C: You write very poignantly about his final days dying of cancer. Now, Lee was a heavy smoker and drinker—did you ever think about gently confronting him about that?

WW: Absolutely not! Lee was his own man. I rarely dared confront him about anything. I might occasionally make recommendations to him about his musical choices - such as the track listing of For Every Solution There’s A Problem, the album of demos I ‘produced’ (his word, not mine) for City Slang Records - but when it came to his lifestyle choices, it was none of my business. He would never have listened to me anyway.

C: For someone who's never heard his stuff, where's the best place for a newbie to start?

WW: Well, that depends upon whether you want to dive into the stuff that was most successful, or the stuff that made him a cult icon to musicians over the years following his big hits with Nancy Sinatra. You can even go back to his early days working with the likes of Duane Eddy and Sanford Clark, if you like. But if you want to know what was so remarkable about the big hits, track down Fairytales and Fantasies, a compilation of some of the best stuff he did with Nancy Sinatra. That was pretty much where I began after first hearing him sing. Once you’ve heard 'Some Velvet Morning’, there’s no turning back.

If you want to explore the solo material, then - though my opinion on this changes all the time - I’d say Trouble Is A Lonesome Town, his debut solo album, is as good a place as any to start. The songs are fantastic - I defy anyone to write about death in a more charming fashion than 'We All Make The Flowers Grow' - but the spoken word introductions to each song are magical too, and offer a wonderful snapshot of the way Lee’s mind worked. If that works for you, then go straight to Requiem For An Almost Lady, one of the most astonishing breakup albums anyone will ever make. Just check out 'Come On Home To Me’.

Finally, if I had to choose just one tune—and that’s tough with a catalog as varied as Lee’s - I’d go with "My Autumn’s Done Come," a song about old age written when he was in his thirties. “Hang me a hammock between two trees/ Leave me alone, damn it, let me do what I please…” I wish he’d lived long enough to enjoy that hammock…