Chicago's High-Speed Police Chases Have Been Killing Innocent Civilians

By Kate Shepherd in News on Aug 28, 2015 4:28PM

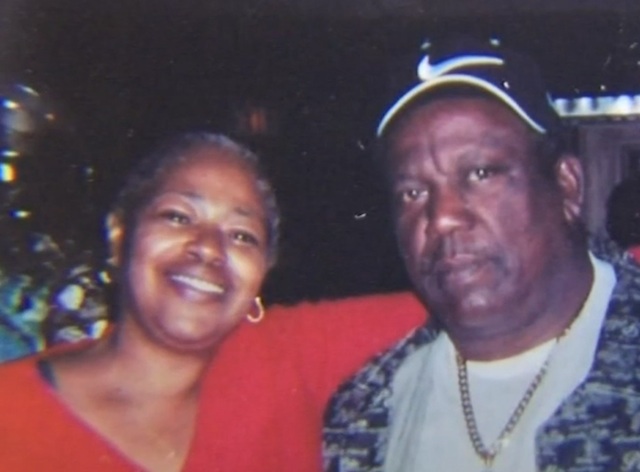

On Monday evening, 66-year-old Willie Owens was changing his truck's battery near his South Side home when a driver fleeing police ran a red light and slammed into the car that hit him.

Owens died and four other innocent bystanders were injured in the crash, caused by a suspect in a high-speed police chase. Before the crash, Paul Forbes, 26, had just been pulled over by police for a traffic violation but he sped off when police officers approached, police told the Tribune.

Owens wasn't the only innocent bystander to be killed by the suspect of a police chase in Chicago this summer. Family members of those who were killed or injured are now asking whether it's time for police to rethink high-speed police chases, particularly if the suspect—as was the case with Forbes—isn't wanted for anything more than a routine traffic violation. In this case, Forbes was driving on a suspended license and without registration.

In the end, Forbes was charged with Owens' murder, one felony count of aggravated fleeing, two felony counts of aggravated battery/great bodily harm, one misdemeanor count of driving on a suspended license and was cited for running a red light and having no registration.

"It wasn't worth it," Xeavier Dale, Owens' girlfriend, told the Tribune.

As Chicagoans have seen in a handful of incidents this summer, high-speed police pursuits and other instances of criminal suspects fleeing the police in cars can have serious and deadly consequences. But are they worth it in the name of police work?

The Chicago Police Department did not respond to our requests for comment on pursuits. A police spokesman said information on the number of police chases conducted by Chicago police this year or in previous years was not readily available.

Police, of course, want to chase the bad guys, but they must balance the immediate need to apprehend the suspect with the risks that come with a chase, Geoffrey Alpert, a leading expert on police pursuits and University of South Carolina criminology and criminal science professor, said in an interview with Chicagoist. A chase is so unpredictable that it can be like "Russian Roulette," especially at intersections where you don't know what's going to happen, he said.

One of the most high-profile recent victims of a police chase suspect was a 13-month-old boy named Dillan Harris. Harris was sitting in his stroller by a Woodlawn bus stop on July 11, when a car being driven by Antoine Watkins struck and killed him. Watkins was fleeing from police after allegedly killing Marvin Carr, a rapper affiliated with Chief Keef. Harris' mother Shatrelle McComb filed a wrongful death lawsuit against the city, the police officers involved in the chase as well as Watkins. The Chicago Police Department responded by offering condolences to Harris' family while placing the blame for his death squarely on Watkins.

"It is an unthinkable loss to which the Chicago Police Department sends its deepest condolences," CPD spokesman Anthony Guglielmi said in an email to the Tribune. "The accountability rests on the suspect in this case who showed no regard for human life but now will answer to justice for his actions."

McComb's attorney Antonio Romanucci chided police in separate statement and asked whether they would have pursued a similar chase through the North Side: "It all circles back to the culture that is instilled in the police department — they never accept responsibility."

Two other crashes during police pursuits in July alone left several innocent bystanders injured.

On July 27, three men and a teenager allegedly fired shots from a minivan and led police on an 8-mile chase that ended with a crash in Chicago Lawn, according to the Tribune. Five people were injured in that crash.

Just two days later, three people were injured when 21-year-old Joseph Demmitt, of Troy, Ohio, crashed a car in Goose Island after fleeing police. Police pursued Demmitt's car after they spotted him speeding in Bridgeport. The chase was called off but later police found out that the car was involved in a crash, authorities told the Tribune.

The incidents raise questions about which suspects are worth pursuing and how police officers can make these very difficult decisions. Chases for suspects in violent crimes such as Watkins' are less controversial.

"At least if it's a violent crime, the police officers have more justification to put people at risk," Alpert said.

However, many police departments are chasing non-violent criminals for traffic crimes, as in Demmitt's case, or stolen vehicles.

"Less than 10 percent are for violent crimes and that's where the police really have to rethink what they're doing," Alpert said. "Chicago in many ways has a progressive police department but, in this area they're way behind the curve."

Many cities with progressive police departments have stopped pursuing criminals for minor incidents but Chicago still does.

Pursuit safety is a problem that extends far beyond Chicago. Nationally at least 5,000 people died in police pursuits from 1979 through 2013. An investigation by USA Today found the death rate is higher now than it was 20 years ago.

But some cities and states have taken policy steps to decrease the number of people killed during pursuits. The number of people who have been killed in police pursuits in Iowa has been steadily declining because of some police departments’ strict policies for high-speed chases, according to the Des Moines Register.

The Des Moines Police Department permits police officers to chase suspects if the officer believes the suspect’s actions outweigh the risk of a chase.

"If the suspect is known and the probability of apprehending him later is high without him harming anybody in between, that would be our preference (to let him go)," Sgt. Paul Parizek, a spokesman for Des Moines police, told the Register. "And that's happened many times."