Photos: A Global Architect Gets His Due At The Art Institute

By Jessica Mlinaric in Arts & Entertainment on Sep 29, 2015 5:23PM

Chicago is a city that reveres its architects. Many can point out Jeanne Gang and Mies van der Rohe’s contributions to the skyline, but some admirers of architecture rarely get a glimpse the process beyond the photogenic facades. A new Art Institute of Chicago exhibit, “Making Place: The Architecture of David Adjaye,” (through Jan. 3) invites visitors to explore the philosophy and process of this globally-renowned architect.

Born in East Africa (Tanzania) to West African parents, London-based Adjaye has incorporated a wealth of cultural references into his nearly 50 projects on four continents. The exhibit surveys his career from designing private residences early on, to civic projects around the world, including the Nobel Peace Center and the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Chicagoans don’t yet have a full-scale Adjaye building to admire, but we may in the near future. The architect is a rumored front-runner to design the Barack Obama presidential library, although no official selection has been announced. Until then, the exhibit is worth a trip across town for its international insight.

Adjaye does not have an instantly-recognizable style compared to an architect like Frank Gehry, whose Pritzker Pavilion looms across the street from the Art Institute. Rather, his work is deeply rooted in the context of each specific site. His Modernist structures result from thoughtful consideration of the project location’s history, culture, and climate. Such details are demonstrated in the colorful glass panes of London’s Whitechapel Idea Store, which references stalls from an adjacent street market, or the subtle rose pattern in Harlem’s Sugar Hill building facade, a nod to the motif repeated in historic neighborhood residences.

Adjaye’s works often incorporate connections from other cultures. The Oslo train station that was renovated to house the Nobel Peace Center recalled West African elements for him. A Moscow business school design addressed the cold climate by combining several buildings into a stacked composition, via inspiration from a Yoruba sculpture.

As Adjaye is quoted in the exhibit, “The final form comes from my African heritage, driven through a (Russian) Constructivist agenda.”

One feels like they are getting their passport stamped moving between pieces in the exhibit, as a silk-weaving factory design in India gives way to a Beirut shopping mall or Washington, D.C. library.

The two-floor exhibit presents the design process in several forms. Hand sketches on display illustrate not only a building’s intended shape, but the use of natural light (represented by halos). The initial gallery of white models allows visitors to examine projects on the same small scale. This approach expands into larger scale, more detailed models in the following galleries accompanied by photo collages, video, furniture design, and a soundscape collaboration with Adjaye’s musician brother Peter.

The exhibit continues shifting forms by highlighting Adjaye’s study of African cities. Over the course of a decade he made a solo survey of 53 African capital cities. Adjaye’s observations on regional architecture, urbanization, and sustainability are viewed through his photographs from these travels and his ensuing city master plans. The final gallery invites visitors to engage with a full-scale work of a pavilion called “Horizon.” Walking through the spruce timber installation invokes a stirring demonstration of Adjaye’s most persistent themes: light, sculpture, community, and sanctuary.

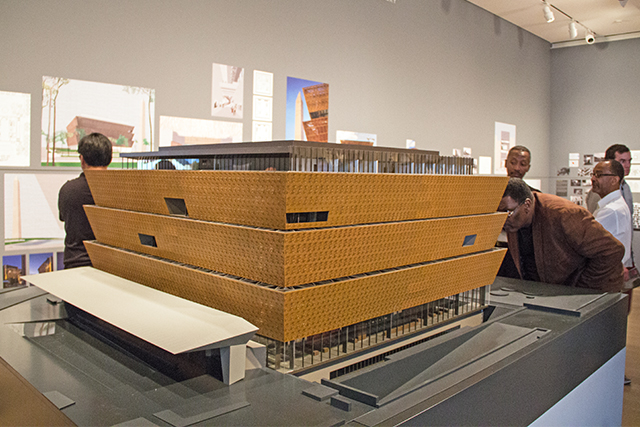

The Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, arguably the most anticipated American building opening of 2016, is a prominent topic in the exhibit and its marketing. The building’s glimmering corona, or crown-shaped exterior panel structure, was inspired by a Yoruba sculpture and recalls the uplifted arms of praise prominent in African American culture. Visitors learn that Adjaye’s team wanted to cast the light filtering panels from solid bronze in an homage to the metalworking craft of free southern slaves. The material was heavy and cost prohibitive so they settled on aluminum coated in liquid bronze. Adjaye sums up the significance of the musuem’s place on the National Mall’s “avenue of palaces of culture,” saying, “the power of the mall is very clear.”

It’s no coincidence that “Making Place: The Architecture of David Adjaye,” runs concurrently with the Chicago Architecture Biennial, the largest international exhibition of contemporary architecture in North America. The exhibit presents architecture as a vehicle for examining the world at the same time Chicago hosts global leaders in design.

“Museums are containers of meaning and also containers of hope,” said Adjaye. So too is thoughtful architecture, when we can recognize the distinctiveness of making a place and see ourselves reflected back in it.