A History Of Chicago's Murder Castle

By Lauren Whalen in Arts & Entertainment on Nov 2, 2015 7:30PM

What to do when you're a bright young physician with striking blue eyes, impeccable manners and a penchant for cadavers? If you're Herman Mudgett, you change your name, relocate to Chicago's up-and-coming Englewood neighborhood and construct your very own house of horrors. As the city prepared to host the 1893 World's Fair, Mudgett-now known as H.H. Holmes-was building the massive structure in which he'd earn the moniker of "America's first serial killer." What follows is a history of Holmes' "Murder Castle"—a twisted mastermind, a media circus and the bloody, cursed aftermath.

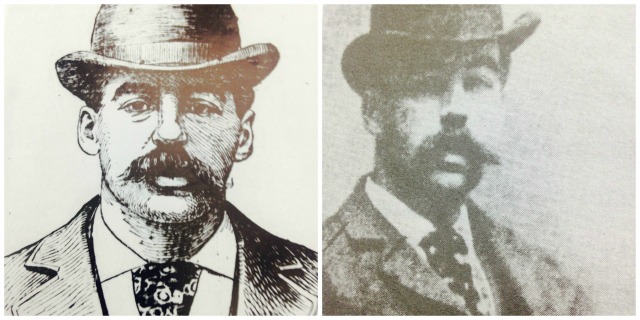

Herman Webster Mudgett, aka H.H. Holmes. Via Illinois State Historical Society (L) and Troy Taylor (R)

The Man

Herman Webster Mudgett was born in 1860, the son of a wealthy and respected New Hampshire family. His life of crime began in medical school, during which he staged accidents using corpses stolen from the local morgue and then collected on insurance policies he'd taken out on the cadavers. Abandoning his wife and child, Mudgett took on the name H.H. Holmes (a respected Chicago family name at the time) and moved to Englewood in 1885 to begin a life as entrepreneur, bigamist, amateur architect and murderer.

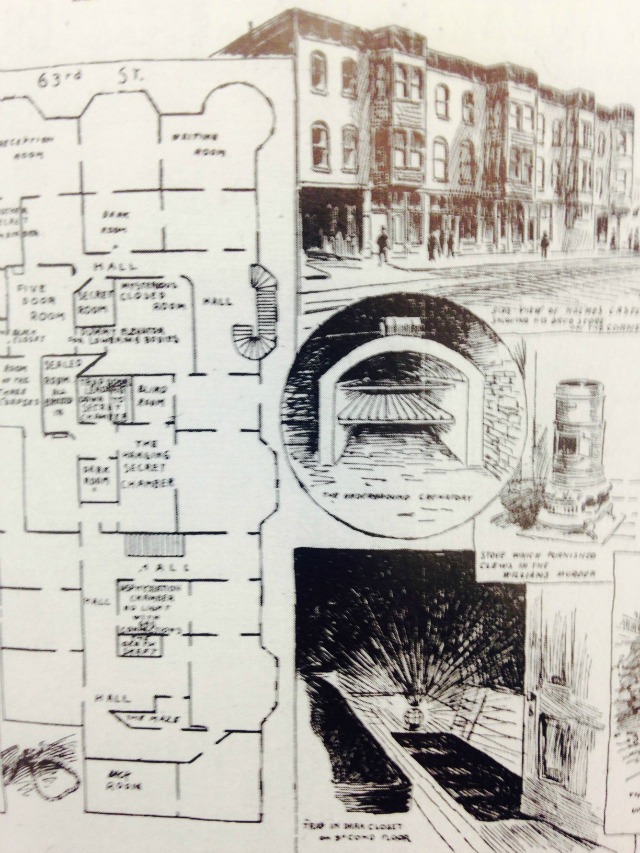

A newspaper illustration of the Castle's floor plan and various torture devices. Courtesy of the Illinois State Historical Library.

The Construction

In 1887, Holmes took over management of an Englewood drugstore after the widow who'd sold it to him mysteriously vanished. After hiring the Conner family from Iowa to work in the store and keep his books—and taking out large insurance policies on wife Julia and daughter Pearl, naming himself as beneficiary—Holmes spent ample time on his self-designed building. Construction should have taken six months but instead took three times as long, as Holmes constantly hired and fired laborers. This saved Holmes a significant amount of money in wages, as he would frequently accuse an employee of substandard work and fire him on the spot without paying a cent. More importantly, by keeping turnover high and ensuring each individual only worked on a small part of the building, Holmes easily hid its design and layout from the world. Soon, the construction attracted a gaggle of gawkers and passersby, including police that Holmes befriended with coffee and the idle chatter at which he excelled.

A rare photo of Holmes' Castle. Photo courtesy of Chicago Historical Society.

The Castle

The imposing structure that Englewood residents nicknamed "The Castle" was located on the corner of 63rd and Wallace streets. Though it wasn't particularly large in this age of skyscrapers, the Castle was certainly intimidating, taking up an entire block. False battlements and wooden bay windows were covered in sheet iron. The Castle boasted a cellar and three floors, the first of which was open to the public. Thousands of people would pass through street-level shops, some operated by Holmes and some leased to local merchants, without a clue of what went on upstairs and below ground.

When the Castle was completed in 1892, Holmes announced that he would rent out rooms to tourists arriving en masse for the upcoming World's Fair (also known as the Columbian Exposition, commemorating the anniversary of Columbus' discovery of America). Indeed, most of the third floor rooms were comfortably furnished and nondescript, provided guests could locate them at all. Rooms were scattered among oddly angled, narrow corridors with poor lighting from widely spaced gas jets on the walls. Dead ends and stairways that led nowhere were interspersed with locked doors to which only Holmes had the key. One of the locked rooms was adjacent to Holmes' personal office and contained a walk-in bank vault that had been modified to include a gas pipe. Only Holmes could control this particular gas flow, via a panel hidden in his bedroom closet.

The second floor was even more confusing, containing 51 doors and six hallways. Thirty-five rooms were ordinary bedchambers, but others were either airtight and lined with asbestos-coated steel plates or completely soundproofed. Some were tiny with low ceilings, no bigger than closets. Most of these rooms were rigged with gas pipes connected to the same control panel in Holmes' closet, and equipped with special peepholes. Many were fitted with alarms that sounded in Holmes' quarters if a "guest" tried to escape. The Castle's second story also contained trapdoors, secret passageways, hidden closets with sliding panels, and most terrifying, large, greased shafts leading directly to the cellar.

Brick-lined and dark, the cellar was comparable to a dungeon, and the various apparatus stored there only added to the terror. Holmes kept an acid tank, quicklime vats, a dissecting table and surgeon's cabinet, and eventually a contraption of his own invention. Holmes called it the "elasticity determinator" and claimed it could stretch experimental subjects to twice their normal height, eventually creating "a race of giants." When police found the device, they compared it to a medieval torture rack.

Newspaper sketch of Holmes and a victim. Courtesy of Illinois State Historical Society.

The Victims

Holmes eventually confessed to 28 murders, though the actual number of victims is believed to be as many as 200. Holmes used two major pretenses to lure guests who checked in and never checked out. First, he advertised lodging for tourists visiting the World's Fair. Second, he would place classified ads in small-town newspapers, offering jobs to young women, or outright offering himself for marriage. (Holmes wedded several times, often to more than one woman at once, using different aliases.)

Because of the World's Fair and then-unsophisticated police procedure, missing persons were barely investigated. Holmes' innate charm could smooth over any remaining questions from neighbors and families. Over time, he claimed that his female assistant went out of town to visit relatives and ended up staying, his fiancée eloped with someone else in secret, and he'd administered a botched abortion to a girlfriend that unfortunately took her life.

The reality, of course, was much more gruesome. Upon investigating the Castle after Holmes was arrested for unrelated crimes such as insurance fraud, police found the rooms and apparati mentioned above, as well as a human-sized kiln that heated to 3000 degrees Fahrenheit and a wooden box containing several female skeletons. (In fact, one of Holmes' main associates, Charles Chappell, was also an "articulator," meaning he could strip flesh from human bodies and reassemble the bones to form complete skeletons. Holmes would frequently pay Chappell to articulate a cadaver, then either keep the skeleton or sell it for a profit to a medical school.)

One of the most disturbing stories was that of Emeline Cigrand, a bright young woman from Indiana who became Holmes' personal secretary. After accepting Holmes' marriage proposal, Cigrand disappeared into thin air. Holmes claimed she ran off with another man, but around she went missing, Holmes asked two male guests of the hotel to help him carry a large, heavy trunk to the cellar. Soon after, Holmes sold a fully articulated female skeleton to a nearby medical school, and during their investigation, police found a woman's footprint clearly etched into the floor on the inside of the cellar's vault. Holmes later confessed to locking Cigard in the vault and raping her before taking her life. He then shipped her trunk full of clothes and personal belongings to her family without explanation. At least one child perished at Holmes' hands: young Pearl Conner was chloroformed and suffocated in her Castle bed.

The End?

Holmes was arrested twice in 1894 for insurance fraud. Investigator Frank P. Geyer of Philadelphia slowly began to uncover Holmes' more disturbing crimes, which eventually led to the Chicago police investigation and subsequent media coverage of what quickly became known as the Murder Castle. Holmes' trial began in Philadelphia just before Halloween of 1895. Only six days in length, it was one of the most sensational of the century. People throughout the country, but especially in Chicago, were equal parts horrified and fascinated by Holmes' confessions of torture and murder. Though his tales may have been embellished, actual evidence ranks Holmes as one of the country's most active murderers.

In his confession, Holmes claimed: "I was born with the devil in me. I could not help the fact that I was a murderer, no more than the poet can help the inspiration to sing." Holmes remained charming, charismatic and unrepentant to the day of his execution: May 7, 1896, just nine days before his thirty-sixth birthday. Even after meeting with two Catholic priests, Holmes refused to ask forgiveness. After Holmes was hanged, his heart continued to beat for fifteen minutes.

As for the Murder Castle, it too met a violent and mysterious end. A man named A.M. Clark purchased the building less than two weeks after the police investigation. Clark intended to capitalize on the Castle's notoriety and reopen it as a tourist attraction. However, on Aug. 19 at 12:13 a.m., a railroad night watchman spotted flames coming through the Castle's roof. Seconds later, explosions blew out the first-floor windows, and the fire was out of control by the time help arrived. Ninety minutes after the fire was reported, the roof had collapsed and most of the building demolished. However, the first floor was salvaged and served as a sign shop and bookstore until the Castle was sold in 1937. In 1938, the lot was sold and the building razed to make way for the U.S. Post Office that remains to this day.

Holmes' bloody legacy didn't die with him. In the years following, men who'd had dealings with Holmes came to strange and violent ends. The last of which was Pat Quinlan, suspected accomplice and former Murder Castle caretaker. On March 7, 1914 (almost two full decades after Holmes' execution_ the Chicago Tribune published the headline "HOLMES CASTLE SECRETS DIE." Quinlan had committed suicide by taking strychnine while living on a farm near Portland, MI. Relatives claimed that in the months before Quinlan's suicide, he seemed to be haunted and could not sleep.

Evan Peters as Mr. March in American Horror Story: Hotel. Photo courtesy of blogs.wsj.com.

The Murder Castle in Pop Culture

Fans of Holmes' story will soon see a version on the big screen: Paramount Pictures has won the film rights to Erik Larson’s bestselling nonfiction book The Devil in the White City, which chronicles the 1893 World's Fair and Holmes' nefarious acts. Martin Scorsese will direct and Leonardo DiCaprio will play Holmes.

If you're looking for a more immediate fix, check out the current season of FX's American Horror Story. Series regular Evan Peters plays J.P. March, a fictionalized 1920s version of Holmes, who constructs Los Angeles' Hotel Cortez to fulfill his bloodlust - and whose murderous spirit haunts the hotel in the present day.

Read More

The following sources used in this story are excellent further reading on H.H. Holmes and the Murder Castle:

• The Devil in the White City: Murder, Magic and Madness at the Fair That Changed America, by Erik Larson

• Depraved: The Shocking True Story of America's First Serial Killer, by Howard Schechter

• Murder & Mayhem on Chicago's South Side, by Troy Taylor