Fridays With Roy: Barry Gifford's New Christmas Story Revisits 1953

By Barry Gifford in Arts & Entertainment on Dec 18, 2015 7:12PM

We hope you've enjoyed our series Fridays with Roy, which now draws to a close with a new Christmas story by Barry Gifford. This story, taken from a work in progress titled The Cuban Club, is the seventh holiday offering in what has become an annual tradition for Chicagoist. It's also unusually sober. But the holidays aren't only a time to celebrate, they're also a moment to take stock of the last twelve months. 1953 seems like a long time ago, but as many tumultuous events of the past year have demonstrated, the shocking racism of that time period is still all too common today.

by Barry Gifford

Roy and his mother had come back to Chicago from Cuba by way of Key West and Miami so that she could attend the funeral of her Uncle Ike, her father’s brother. Roy was six years old and though he would not be going to the funeral—he’d stay at home with his grandmother, who was too ill to attend—he looked forward to seeing Pops, his grandfather, during his and his mother’s time in the city.

It was two weeks before Christmas and the weather was at its most miserable. The temperature was close to zero, ice and day-old snow covered the streets and sidewalks, and sharp winds cut into pedestrians from several directions at once. Had it not been out of fondness and respect for her father’s brother, Roy’s mother would never have ventured north from the tropics at this time of year. Uncle Ike had always been especially kind and attentive to his niece and Roy’s mother was sincerely saddened by his passing.

She and Roy had first stopped on the way in from the airport to see Roy’s father, from whom his mother had recently been divorced, at his liquor store, and were now in a taxi on their way to Roy’s grandmother’s house when she told the driver to stop so that she could buy something at a pharmacy.

“Wait here in the cab, Roy,” she said, “it’s warmer. I’ll only be a couple of minutes.”

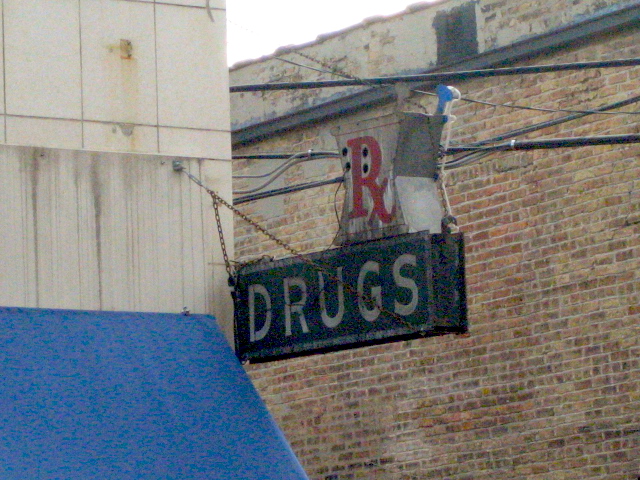

Roy watched his mother tiptoe gingerly across the frozen sidewalk and enter the drugstore. The taxi was parked on Ojibway Avenue, which Roy recognized was not very far from his grandmother’s neighborhood.

“That your mother?” the driver asked.

“Yes.”

“She’s a real attractive lady. You live in Chicago?”

“Sometimes,” said Roy. “My grandmother lives here. Right now we live in Havana, Cuba, and Key West, Florida.”

“You live in both places?”

“We go back and forth on the ferry. They’re pretty close.”

“Your parents got two houses, huh?”

“They’re divorced. My mom and I live in hotels.”

“You like that, livin’ in hotels?”

“We’ve always lived in hotels, even when my mom and dad were married. I was born in one in Chicago.”

“Where’s your dad live?”

“Here, mostly. Sometimes he’s in Havana or Las Vegas.”

“What business is he in?”

Roy was getting anxious about his mother. The rear window on his side of the cab kept steaming up and Roy kept wiping it off.

“My mother’s been in there a long time,” he said. “I’m going in to find her.”

“Hold on, kid, she’ll be right back. The drugstore’s probably crowded.”

Roy opened the curbside door and said, “Don’t drive away. My mom’ll pay you.”

He got out and went into the drugstore. His mother was standing in front of the cash counter. Three or four customers in line were behind her.

“You dumb son of a bitch!” his mother shouted at the man standing behind the counter. “How dare you talk to me like that!”

The clerk was tall and slim and he was wearing wire-rim glasses and a brown sweater.

“I told you,” he said, “we don’t serve Negroes. Please leave the store or I’ll call the police.”

“Go on, lady,” said a man standing in line. “Go someplace else.”

“Mom, what’s wrong?” Roy said.

The customers and the clerk looked at him.

“This horrible man refuses to wait on me because he thinks I’m a Negro.”

“But you’re not a Negro,” Roy said.

“It doesn’t matter if I am or not. He’s stupid and rude.”

“Is that your son?” the clerk asked.

“He’s white,” said a woman in the line. “He’s got a suntan but he’s a white boy.”

“I’m sorry, lady,” said the clerk, “it’s just that your skin is so dark.”

“Her hair’s red,” said the woman. “She and the boy have been in the sun too much down south somewhere.”

Roy’s mother threw the two bottles of lotion she’d been holding at the clerk. He caught one and the other bounced off his chest and fell on the floor behind the counter.

“Come on, Roy, let’s get out of here,” said his mother.

The taxi was still waiting with the motor running and they got in. The driver put it into gear and pulled away from the curb.

“You get what you needed, lady?” he asked.

“Mom, why didn’t you tell the man that you aren’t a Negro?”

Roy’s mother’s shoulders were shaking and tears were running down her cheeks. He could see her hands trembling as she wiped her face.

“Because it shouldn’t matter, Roy. This is Chicago, Illinois, not Birmingham, Alabama. It’s against the law not to serve Negroes.”

“No it ain’t, lady,” said the driver.

“It should be,” said Roy’s mother.

“How could they think you’re black?” the driver said. “If I’d thought you were a Negro, I wouldn’t have picked you up.”