WBEZ's Natalie Moore Tackles Segregation In Chicago In Her New Book

By Chicagoist_Guest in Arts & Entertainment on Mar 24, 2016 6:59PM

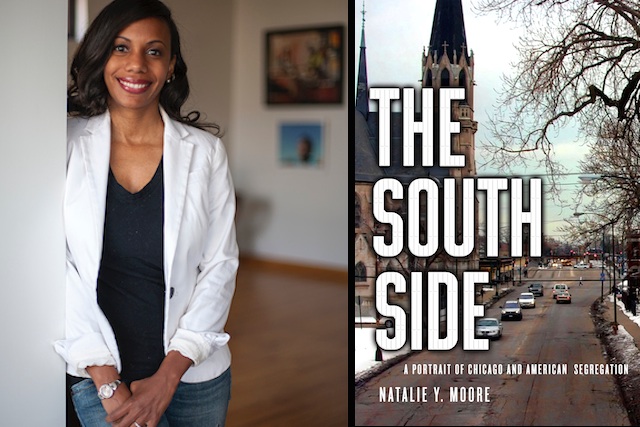

Natalie Moore and the cover of her new book (portrait by David Pierini; cover photo courtesy of St. Martin's Press)

By Adrienne Samuels Gibbs

The South Side. What images do you see when you read those words? I see manicured lawns, block club signs, corner stores, Harold’s Chicken, the Museum of Science and Industry and the red brick of my high school alma mater, Morgan Park. I see baseball games and horseback riding at Washington Park, fine art at Gallery Guichard and the best fries and mild sauce ever created at Home of the Hoagy off 111th Street. But people not from here often see something different, due to attitudes brought about by segregation.

Reporter Natalie Moore, of local NPR station WBEZ, celebrates the genius and good of the South Side as well as the reasons for segregation and its legacy of inequity in her very personal treatise, The South Side: A Portrait of Chicago and American Segregation, which came out Wednesday. It’s a deftly-handled look at how the South Side came to be mostly black and brown, and the government policies that have supported the city’s racial divisions. Moore focuses her analysis on a handful of neighborhoods. She describes how segregation helped to shape the middle class families of Chatham, including her own; how poverty and race affect Englewood’s grocery store options; how one community, Beverly, very deliberately pushed for integration in the '80s; and why downtown restaurants get away with selling pricier, less tasty versions of the donuts and barbecue on the South Side.

What makes this book work for me is that Moore tackles the sociological, political and historical while mixing in personal anecdotes from her own life as a child of Great Migrationists. She talks about tough stuff, like how segregation affects home values and therefore affects wealth-building in the black community. Moore also deals extensively with how segregation has affected Chicago Public Schools, and whether life was better for black people before or after integration—which has apparently failed. I’ve never read a book about Chicago that so closely mirrors my own experiences or places said experiences in such rich historical context. The work is illuminating, as was the conversation Moore and I had about it. (Full disclosure: I’ve known Moore for years. We even went to elementary school together.)

It seems like it's hard for people to admit that segregationist policies still affect the South Side today. Why is it that?

It has a lot do with segregation and how people don’t have contact with other races, which is one thing that I say in the book. Maybe we should start saying "white segregation," because white people are just as segregated as black people. If you don’t have exposure or interactions with people outside of the person you have coffee with at work, I think it’s very easy to just blame people. It’s easy to say they are to blame for their conditions, and not really understand how those conditions happened in the first place.

We went to the same elementary school—Sutherland, in Beverly—and you were bussed in from Chatham while I walked to school. In the book, you discuss in the civil rights mandate to integrate Chicago Public Schools. Did your parents ever talk with you about how your presence was, quite literally, the integration everyone sought?

My parents knew I wasn’t going to be confronting violence, there was no need to have this talk. There wasn’t resistance from the community of Beverly. At that time it was trying to be integrated and they thought that the schools were a good way to do it. You didn’t have BAPA (Beverly Area Planning Association) opposing it. You didn’t have parents with picket signs. For us it was just “take the bus to school.”

Still, you—a Chatham kid—made CPS history. Did the integration work, from your perspective?

Yeah. I suppose so... There was no black track. There was no white track.

In your book you detail why you eventually moved to Hyde Park after the housing market crash. You combine this with reporting on Bronzeville’s vibrant business community, juxtaposed with reporting on why appraisers undervalue homes in segregated black communities. What’s happening now in Bronzeville and how can we all help the area recover?

I like to think the market is resetting. I talk about that in the book. With lower prices you get some new people in with some elbow grease who are committed to the neighborhood who will pay what it’s actually worth, who are actually paying $70,000 for my condo versus the $172,000 I paid. I also think there was a condo glut instead of real planning around these issues. I left mainly because I had to get a bigger place in Hyde Park, because of family size. But I still support Bronzeville. It’s right next door. I go to Peaches. I wanted my book launch to be in Bronzeville.

For me it’s not washing my hands like I’m done because I’m in greener pastures. I deeply care about Bronzeville, and I want to see it improve. It affects the neighborhood if I walk away. I was very conscientious in making sure that I was doing things not just for my benefit but that I didn’t leave the neighborhood behind or even the people in my condo association behind.

I meet so many people who have never traveled south of the South Loop. How do you respond to people who ask you loaded questions about working on the so-called “dangerous” South Side, where more than half of Chicago lives?

There is nothing wrong or unsafe on 75th Street. I’m fine being here, and I never want to be so disconnected to black communities that I feel like, ‘oh I can’t be there.’ I get my hair done on 79th Street. I work on 75th and my job takes me all over the South Side. Part of my passion is reporting on disparities and pointing out why things are the way that they are. It’s on purpose and it’s not because black people are fucked up.

I learned a term from you, “retail leakage.” It refers to the millions we South Siders spend downtown, on the North Side and in the suburbs because, largely, we can’t shop local. How can all of us help the South Side?

I was raised to support black business and small business. I do think there has to be more intentional spending in Bronzeville and other places so other businesses can come.

What effect do you want your book to have on readers?

I want us to have a conversation. Why did Ferguson erupt? Why did Baltimore erupt? Why didn’t Chicago erupt? I hope people talk and read more. I hope this is educational and we start thinking about our city in the lens through which it has been defined since the 20th century.

Can we overcome the government-sanctioned pattern of racism and segregation that you describe in your book?

I have to be optimistic. Humanity makes that very difficult.

Last question: Now that your book is out, how will you deal with the trolls?

I hope the Internet trolls read my book.

This conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Moore’s book is on sale online and at book stores everywhere.

Adrienne Samuels Gibbs is an award-winning writer whose work has appeared in Vice, The Boston Globe, The Miami Herald, Essence and the Chicago Sun-Times. Follow her @adriennewrites.