Photos: Exploring Illinois' Abandoned Psychiatric Hospitals

By Hale Goetz in News on Apr 1, 2016 3:59PM

Abandoned psychiatric institutions linger in the bustling landscape of Chicago and its outskirts, their shells the relics of a past era. Dr. Johnny Williamson, current medical director of the Community Counseling Centers of Chicago (commonly referred to as C4), tells Chicagoist that these emptied buildings are a window to the past.

"I think we learn a lot about what we've done when we look at places we've abandoned," Williamson says. "You can see what happened there and compare to where we are."

In the images above, photographer Matt Tuteur captures the aftermath of the boom of mental health care facilities around the turn of the last century. To follow the trail of these abandoned facilities, it's easiest to start at the beginning.

Before the 19th century, doctors thought isolation was the best solution for mental illness. The mentally ill were viewed as religiously sick—either through possession or a lack of faith. This attitude began to change with the efforts of American activist Dorothea Dix, who partook in what was known as the "lunacy reform" in Great Britain. She returned home to the States to investigate the current state of mental health care facilities, which lacked regulations and funding. Dix began working around the United States to bring reform, and in 1847, her report in Illinois was instrumental in the state’s decision to open its first mental hospital. (The first mental hospital was opened in Jacksonville in 1851, and the center was used up until 2012, though its focus had shifted toward the developmentally challenged.)

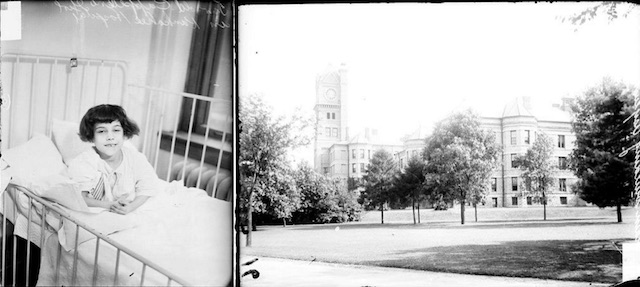

Portrait of a 5-year-old girl in 1928, last name Cappelleno, looking toward the camera, sitting in a bed in a room at Kankakee Hospital in Kankakee, Illinois. The hospital is pictured right in 1928. (Photo from the Chicago Daily News via the Chicago History Museum)

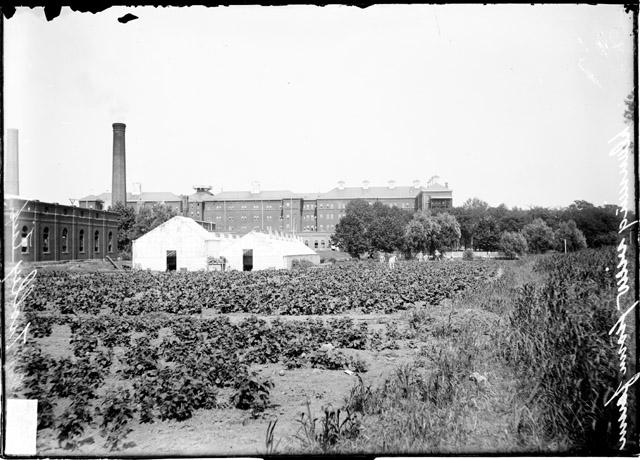

The growth that followed was exponential. By 1904, over 150,000 patients lived in mental hospitals in the United States, and that number grew rapidly. Many of these psychiatric hospitals were built just outside the city or at its edges. Some of these facilities were created with the best intentions, and well-regarded architects were brought in with the goal of creating serene spaces, often in the countryside. Many Cook County residents were transported to facilities outside city limits, like Kankakee Hospital or Manteno State Hospital, which were both about over 50 miles away from The Loop. Even Dunning, which is in Chicago proper, looked positively serene:

View of the Chicago State Hospital buildings as seen from across the farm, in the Dunning community area of Chicago, Illinois in 1908. This image was taken as part of a Chicago Railways Company Trolley Trip. (Photo via the Chicago History Museum)

View of a lagoon at the Chicago State Hospital, formerly known as Dunning Mental Institute, in the Dunning community area of Chicago, Illinois. This image was taken as part of a Chicago Railways Company Trolley Trip. (Photo via the Chicago History Museum)

But despite the efforts of mental health care advocates and activists like Dix, many mental hospitals were terrible places to live. Patients in mental hospitals were impoverished and tightly packed into these facilities. Chicago State Hospital, nicknamed Dunning for its location, is perhaps one of the most notorious in Illinois. Rife with corruption and packed with cloistered residents, Dunning lacked the resources to properly care for its residents. A 2013 WBEZ report notes, "Even under the best of conditions, doctors didn't have many effective treatments for people suffering from mental illness. The only drugs they had at their disposal were sedatives."

Inmates at the Chicago State Hospital, known as Dunning, walk outdoors on a snow-covered path on Dec 10, 1910. (Photo from the Chicago Daily News via the Chicago History Museum)

Women sit on a piece of furniture placed on the lawn near a building at the Dunning Mental Institute after a fire on April 13, 1915. (Photo from the Chicago Daily News via the Chicago History Museum)

Following the return of traumatized soldiers from WWII, the National Mental Health Act in 1946 called for the establishment of the National Institute of Mental Health, which was given a budget for the research and development of America's mental health care. Regulations became stricter. Psychiatric units were added to pre-existing hospitals, and the population of the overcrowded and under-managed mental health institutions fell. The abandonment of the practices was swift, leaving huge facilities open and gutted.

Today we're still wrestling with the best way to treat patients with mental illnesses. The patients who would be residing in places like Dunning in another era have been largely shuffled into other government institutions or abandoned completely. Lincoln Park Community cites the number of homeless individuals with mental illness at 26 percent. The Atlantic's article “America's Largest Mental Hospital Is a Jail,” explores Cook County Jail, where an estimated one-third of the prison population suffers from mental illness. Reporter Matt Ford writes:

One kid on the list had a tendency toward aggression, but officials emphasized that the overwhelming majority were "crimes of survival" such as retail theft (to find food or supplies) or breaking and entering (to find a place to sleep). For those with mental illness, charges of drug possession can often indicate attempts at self-medication.

C4—where Williamson works—is a third option. As a community of outpatient clinics, C4 provides for people with mental illness, especially those recovering patients who have recently left psychiatric care. C4 aims to offer "quality, comprehensive customer-oriented services tailored to the diversity of its consumers."

But Williamson notes the difficulty of their mission: "Mental health affects a person’s functioning across all levels...If I have a broken arm or I have diabetes, there are certain areas of my life that will suffer, but if I have schizophrenia or depression, every waking aspect of my life is impacted. You end up with a lot more barriers to treatment."

Williamson cites budgetary restraints as the largest obstacle for organizations like C4. "The needs of the severely and chronically ill are varied and multiple, especially since these illnesses are often not curable and often enduring — it's increasingly more difficult to manage the care of them within the confines of what is currently considered reimbursable."

The National Alliance of Mental Illness (NAMI), when examining the state mental health budgets for 2016, called their findings "troubling." Only 23 states increased their budgets, 12 were decreased, and the rest stayed the same—with the exception of Illinois and Pennsylvania, whose budgets were still unfinished when the report came out. In the meantime, practices like C4—who services a large number of patients on Medicaid—are treading water.

As Williamson explains, "You can't provide a service that you can't get reimbursed for, so the way that reimbursement occurs ends up shaping how these services can be provided instead of the other way around."

But when asked about the future of mental health care, Williamson laughs. "I'm an optimist," he says, "and I do believe we find ways to continually provide care." Williamson notes the advancements in medication, as well as the access and opportunity an increase in technology has provided. "The trick becomes how to mix and match and get the things that are likely to be effective to the people who would benefit from them."

"Illinois is just like any other place in its challenges, but I think it's also unique in the depth and the breadth," says Williamson. "You have to be able to function with a high level of uncertainty to be effective."

Hale Goetz is a 20-something Chicago suburbanite and D&D enthusiast. She writes about feminism, identity, and guilty pleasures. You can find more of her work here or follow her on Twitter.