Can Anyone Stop Pilsen From Gentrifying?

By Mae Rice in News on Jun 28, 2016 6:24PM

This is a two-part story. Read Chicagoist's man-on-the-street interviews with Pilsen locals here.

In Pilsen, a block or so east of the bar Simone’s, an empty lot runs from Peoria Street to Newberry Avenue, from 18th Street back to 16th Street. Half concrete, half scrubby grass punctuated by giant thistles, it’s surrounded by rental chain link fencing, some of which has fallen down. This parcel of land has been palpably vacant for years, and nothing will fill the void anytime soon. Earlier this month, Pilsen’s alderman—Ald. Danny Solis (25th)—finished the multi-month process of blocking a housing development planned for the lot.

Developer Property Market Group (PMG)—which has offices in New York, Chicago and Miami— planned to build 500 units there in April of 2015, Crain’s reported. PMG did not, however, plan to meet Pilsen’s affordable housing quota: 21 percent, more than twice the 10 percent quota enforced citywide. Solis never approved PMG’s project, but as of March, PMG didn’t care. They planned to move forward on it anyway. This was risky, but technically feasible; the lot had been zoned for up to 300 units of housing back in 2008, Solis told Chicagoist, for a different project whose developer folded in the 2008 housing crash.

This past April, Solis countered PMG's development plan by introducing an ordinance to the city’s Committee on Zoning (of which he is chairman) that would rezone the vacant lot, making PMG’s plans impossible. It passed City Council on June 22; PMG can no longer legally build on the lot, no matter how much they want to.

This is present day Pilsen in a nutshell. The neighborhood is caught between two forces: the push to preserve its Latino, working-class identity, which you can see in the local affordable housing quota; and an opposing push, from parties like PMG, to capitalize on the area’s proximity to the Loop and University of Illinois at Chicago—and its Latino identity, too, for that matter. The neighborhood is caught, in a way, between its housing quota and developers. Or, to put it another way, Pilsen is caught between Bow Truss Coffee Roasters and its vandals.

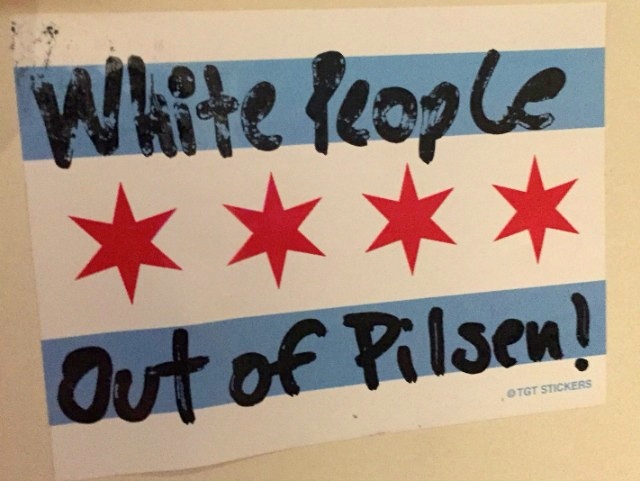

Photo by Bow Truss founder Phil Tadros

If you live in Chicago, you almost definitely heard about this. In October of 2015, someone posted a Chicago flag sticker on the Pilsen Bow Truss’s window, with “White people out of Pilsen” markered over the flag’s blue stripes. Before that, in January of 2015, Bow Truss was vandalized with anti-gentrification signage duct-taped over the windows. “This is what gentrification looks like,” read one sign.

The Bow Truss vandals’ underlying analysis makes some sense: White people moving into Pilsen has certainly correlated with major demographic shifts. Pilsen has been a predominantly Latino, working-class neighborhood since the 1960s. It remains that way, too—every census tract in Pilsen was majority Latino in 2013—but those residents have left the neighborhood by the thousands in recent years, and the white population has grown, according to a new analysis of census data. White Pilsen residents make more, on average, than their Latino counterparts, according to that study, and their arrival has coincided with a rise in Pilsen’s median monthly rent (from $483 in 2000 to $778 in 2013).

White people moving out of Pilsen wouldn’t necessarily reverse these shifts, but the shifts bring with them an understandable sense of loss. Byron Sigcho, director of The Pilsen Alliance—a non-profit community organization devoted to preserving Pilsen’s culture and preventing mass displacement—pinpointed the issue: “How are you going to have a Mexican neighborhood without Mexicans?”

Mexican neighborhoods are “valuable,” financially as well as culturally, Sigcho told Chicagoist. “Talk about how valuable tourism can be, when you have an iconic neighborhood like Pilsen. A culturally rich place!” he said. But “we [at the Pilsen Alliance] see so many residents being displaced,” he added, as rents rise and Pilsen gentrifies.

In Pilsen, Bow Truss and shops like it really are “what gentrification looks like,” as the vandals put it. Often, people associate gentrification with massive redevelopment projects, such as Logan Square’s influx of transit-oriented apartment complexes. In the past five years, though, there have been few large-scale private housing developments in Pilsen. In mid-April, Solis told Chicagoist that in the past five years, he’s only signed off on one private housing development in Pilsen.

This means a lot of the change in the area is development on a smaller scale, which Solis says is “very difficult” to regulate. New, upscale businesses like Bow Truss haved moved in. Bow Truss itself opened in 2014, capping off a wave that started with Simone’s in 2009, followed by gastropub Pl-zen in 2012 and Thalia Hall, a historic landmark since 1989, opening in its current, Dave Chappelle-hosting incarnation in 2013. Pilsen’s homes and two- and three-flats are also getting rehabbed or, less frequently, torn down and replaced. In 2015, there were 234 building permits issued in Pilsen, according to Chicago Cityscape. Just over 80 of them were for renovating and/or altering existing structures; five were for building new ones.

Pilsen may be gentrifying, but it’s not gentrified—at least not according to Eric Winter. Winter, a half-Hispanic man whose mother grew up in Pilsen, opened a yoga studio in Pilsen back in February of 2015. He works as a massage therapist as well as a yoga teacher, and one of his massage clients pointed him toward the area.

“I was told that Pilsen’s been gentrifying for like, two years already,” Winter told Chicagoist. “So I was sort of hoping that this place would have been done by now.”

It’s not. Winter has struggled to get clients to come out to his studio, PFIT Yoga, even though it’s across the street from beloved dive Skylark and there are scant other yoga options in the area. He acknowledges every new business faces challenges, but he worries safety concerns have kept students away from his hardwood-floored yoga loft. As of early May, the city’s crime map showed six criminal incidents within a block of the Winter’s studio in the past year, half of them assaults.

In early May of this year, the crime affected Winter personally: someone tried to break into the PFIT studio. Winter told Chicagoist that based on his building’s camera system, the intruder broke in in “broad daylight.” Judging by the damage to PFIT’s entrance, Winter said the intruder “tried to unscrew the framing on the door.” Winter posted a picture of his damaged door to PFIT’s Facebook, captioned, “Maybe [it’s] a hint to cut our losses and consider a different location?”

Winter told Chicagoist in early June that he didn’t plan to break his lease, which runs through May of 2018. He’s looked at the attempted break-in as one of the growing pains of gentrification. “The [Paseo] trail [announced in March]… is the start-off point of the full gentrification,” he said. (Sigcho’s Pilsen Alliance agrees.)

In less than a month, though, he had changed his mind. Due to police reports of gun violence in his area, Winter said he had decided to move, likely to Swallow Cliff outside the city. At that point, mid-June, the city’s crime map showed seven incidents within a block of his studio, five of them assaults.

The changes in Pilsen that drew Winter to the area were set in motion almost twenty years ago, when government-assisted development changed the area forever. The late ‘90s was an era of two new TIF districts in Pilsen: the Pilsen Industrial Corridor TIF, created in 1998, which funded construction of various factories and warehouses; and the Roosevelt/Union TIF, created in 1999, which helped fund UIC’s south campus expansion.

What is a TIF district? Bear with us for just one paragraph and we’ll explain. (You can also watch this video explainer from Curious City.) TIF is an acronym for “Tax Increment Financing.” When an area is designated a TIF district, a designation that lasts for 23 years, the property taxes that area pays to the city freeze at their existing levels. If local property values (and therefore property taxes) increase, extra tax dollars get diverted into a special fund: the TIF, reserved for development projects in the district that would not happen “but for” government assistance.

Whether a project meets the “but for” requirement is, of course, impossible to know, as are a lot of things about TIFs. They’re widely critiqued for their opacity; Tom Tresser, founder of the TIF Illumination Project, terms TIFs an “off-the-books budget.” However, recent transparency around how TIF funding has historically been allocated has shone a light on how TIFs affected late ‘90s Pilsen.

First, the Pilsen Industrial Corridor became a TIF district. Solis said that he used funding from this TIF to clean up contamination left behind by the heavy industry giants, like Western Electric and ComEd, that departed from Pilsen’s riverbanks “around the ‘70s.” Solis also used funds from this TIF to replace the industrial corridor’s old infrastructure, and attract new “light industry” to the area by helping fund factories like the Steiner Linen Factory. This TIF has created roughly 5,000 jobs, by Solis’s estimate.

“If you look at the zip code of the employees… most of those jobs went to people from Pilsen,” he said.

A year later came the Roosevelt/Union TIF, which made UIC’s south campus possible with $50 million in TIF funding. (Back in 1998, a UIC spokesman told the Reader the project might not go forward without this funding.) Solis supported this “controversial” TIF, he said. By way of explanation, he compared Pilsen to a town in downstate Illinois—if a major university planned an expansion near this hypothetical town, “that town would be exuberant, because that development would create jobs, would create an economic boom.”

Whether Pilsen residents ever bought into this reasoning is unclear, because it never mattered. Legally speaking, residents have to be looped in when a TIF is being created, through public notices and community meetings where they can voice concerns. As a 1998 Tribune story about “the Pilsen TIF” (it’s unclear which one) explains, these meetings had to meet strict guidelines: interpreters had to be available to Spanish speakers, and community members got a minimum of three minutes to speak. Still, as Tresser explained to Chicagoist, “You can bring a million people with you [to the community meetings], but you don’t have the power to veto.”

Solis argues that the UIC expansion brought exactly the economic uptick he foresaw. But Sigcho—who ran against Solis in the 2015 aldermanic race, and accused him of voter fraud—argues that UIC’s expansion triggered a wave of gentrification that’s put Pilsen’s Mexican identity under siege. It’s not quite enough gentrification to fill up Winter’s yoga studio, but it’s definitely enough to attract interest from private developers.

Developers want to build in Pilsen for many of the same reasons Winter wanted to move there: the location and the rising real estate values. In 2015, Crain’s Chicago reported plans for two major new developments in Pilsen: R2’s plan to convert the vacant warehouse at 465 W. Cermak into an office, and PMG’s 500-unit development on 18th Street. Solis said he’s “never heard of” the R2 warehouse conversion, and he’s moved to block PMG’s development. The only development he’s approved in the past five years, he said, is a 99-unit development in the 1400 block of 21st Street, less than a block from Benito Juarez Community Academy.

He rejects most projects, he said, because they don’t meet Pilsen’s affordable housing quota, set at 21 percent for developments of eight units or more. The quota was established by Solis and the Pilsen Land Use Committee, composed of representatives from assorted community organizations, and it’s “higher than any other neighborhood in the city,” according to Solis.

“A mixed-income community, I think, is the best community,” he said.

Critics from both ends of the spectrum take issue with Solis’ approach to new housing developments in Pilsen. Sigcho criticized the Pilsen Land Use Committee for its lack of transparency and its failure to loop in the community on each decision.

“If the people want to see [a giant housing development], let’s do that!” he said. He also noted that, though the committee prevents large new housing developments, it does nothing to prevent or regulate “investors that buy small properties in large quantities.” John Podmajersky III, for instance—a campaign donor of Solis’s—owns giant tracts of small properties in East Pilsen.

Meanwhile, PMG principal Noah Gottlieb declined to talk on the record about PMG’s now-thwarted Pilsen development. However, he instead sent Chicagoist a Washington Post story from February—headlined “The poor are better off when we build more housing for the rich”—that presumably encapsulated his opinion. The story argued that rather than tightly regulating new housing, areas fighting gentrification should encourage new housing, affordable or not. Rooted in data from California’s Bay Area, the argument was a simple supply-and-demand one: the larger the supply of housing, the lower rents will be in a city or neighborhood. Because of this, even high-end new housing will arguably keep a neighborhood’s rents lower than no building at all. (New, luxury housing also becomes more affordable housing as it ages, the piece argues; luxury apartments now will be housing for the middle class 30 years from now.)

Really, Solis’s critics and Solis himself, who said there’s little he can do about small-scale development in Pilsen, are arguing the same thing. Pilsen is in flux, and no one feels in control of how it’s changing. Rightly so. Everyone sees someone else as the deciding factor in how Pilsen evolves; really, no one is. Even an ultra-conservative Pilsen Land Use Committee can only do so much. Committee or no, Pilsen landlords will still hike rents because they can. New restaurants will still pop up along 18th Street, like Dia De Los Tamales—a place so geared towards newcomers that it has a definition of “tamales” on its homepage.

Photo by Mae Rice/Chicagoist

The push and pull between culture and capitalism in Pilsen is perhaps best encapsulated by a riverfront warehouse on Cermak, the one that R2 may or may not convert into an office. Built in 1909, the warehouse has been recommended as a historic landmark. It certainly used to be ornate, but now it’s visibly vacant, covered in graffiti, dotted with missing window panes.

Look at this warehouse from across the Chicago River, and you’ll see a mural just below the roof on the building’s south end. It’s a hundred times bigger and more purposeful than the chicken-scratch graffiti at street level. “MEMORIES ARE SACRED,” it reads.

So many people, from Danny Solis to Byron Sigcho to whoever requested historical status for the warehouse in question, echo this graffiti’s sentiment: that Pilsen’s recent past, as a working-class, predominantly Latino area, is sacred and worth preserving. The tug of war in Pilsen right now is over exactly how sacred it is compared to other sacred American things: money, rehabbing rentals, forgetting.