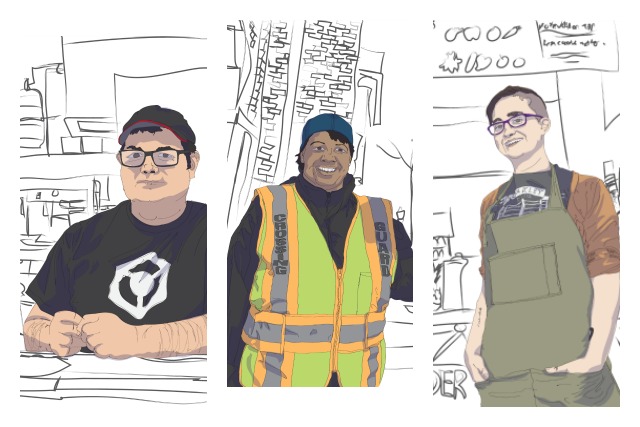

6 People We Met On 18th Street Tell Us How Pilsen Is Changing

By Chicagoist_Guest in News on Jun 28, 2016 6:00PM

Illustrations by Daniel Rowell

By Jackie Serrato

This is a two-part story. Read Chicagoist's companion feature story on gentrification in Pilsen here.

What happens in Pilsen always shows up on 18th Street, the commercial vein of the neighborhood. In the twentieth century, when working class Mexican immigrants first congregated in the area, a wave of family-owned establishments, murals and social justice organizations sprang up on 18th Street. Today, rising rents and unprecedented TLC from City Hall are driving out Latino residents by the thousands—and that transition, too, shows on 18th Street, especially the stretch between Racine Avenue and Throop Street. It’s a microcosm of the new Pilsen (Thalia Hall and its Michelin-starred gastropub, Dusek’s) and the old Pilsen (St. Procopius church, a decades-old pizza joint). We spent three weekday afternoons in April talking to people on these two blocks about their lives in Pilsen, how they see the neighborhood, and what 18th Street means to them.

Illustration by Daniel Rowell

Daniela Villagomez

Transportation Security Officer at O’Hare Airport // 25 years old

Villagomez was born and raised in Pilsen as part of a family of six. Her parents used to be homeowners on 16th and Wood streets, but they lost the house in the middle of the 2008 recession. Now, she and two of her siblings live with their parents still, on 18th and Hoyne streets, paying $850 a month for a two-bedroom apartment.

“Gentrification is a constant worry because we don’t know how much longer we can afford to be here,” she said.

For now, she works at O’Hare Airport and helps her siblings coach softball at Harrison Park. She doesn’t socialize on 18th Street, she said, because she feels it’s not meant for people like her, but rather for “the white college students and the tour buses.”

A month ago, Villagomez led a silent protest during the traditional Via Crucis Easter procession on 18th Street, walking with three other Pilsen youth holding signs bearing messages like “Gentrification is not inevitable.” She thought the reenactment of Jesus’ crucifixion was an appropriate time to mourn the families who’ve been displaced. She can name the people who have moved off her block.

“Even the grocery store that was across the street was taken over by a bank,” Villagomez said. Her fondest memory of her old neighborhood is walking down 18th Street holding her father’s hand and “saying hello to everyone and everyone knowing his name.”

Illustration by Daniel Rowell

Alexandra Curatolo

Owner of Belli’s Juice Bar // 29 years old

Two and a half years ago, Alexandra Curatolo was studying Urban Planning at UIC when she decided to open her own business serving locally-sourced health food. So she opened Belli’s Juice Bar, on the same block as trendy Thalia Hall. Its chalkboard menu advertises vegan, gluten-free smoothies and salads that sell for between $5 and $7.

“I wanted to support local families, local food, farmers, fair wages—it was a whole social justice mission,” she said.

Curatolo herself has lived in Pilsen for eleven years. “Saying hi to your neighbors is something that Pilsen taught me,” she said.

Years before she opened her juice bar, though, the area almost sent her packing. The family-owned apartment building she rented in, at 21st and Halsted streets, sold to a new owner who hiked rents by 70 percent, she said, forcing her to move; luckily, she found a new place at 17th Street and Racine Avenue. Curatolo, born and raised on the South Side, knows Pilsen is gentrifying because she studied the process in graduate school, but she’s also personally felt the effects.

Illustration by Daniel Rowell

Israel Hernandez

Owner of Prospectus Gallery // 57 years old

Prospectus Gallery was the first gallery space on 18th Street, according to owner Israel Hernandez, and he took a winding road to opening it. Hernandez immigrated to the United States from Zacatecas, Mexico in 1972, and was a general laborer in the produce business before he founded the art space in 1991. As a young man living in Pilsen, he used to walk by a mural on a daily basis—”Homenaje a Diego Rivera” on 18th and May—which piqued his curiosity about the arts. He wanted to expose Latino youth in Pilsen to the work of Latin American artists, and give these artists recognition in an often elitist art scene. “We’ve shown exhibits from the best Chicago artists, not only Latino but in general,” he said. That includes artists living and dead, such as Ed Paschke, Carlos Cortez and Hector Duarte. Hernandez provided a formal exhibition space at no cost back when Pilsen artists were struggling to pay for studio space. Lately, “many of my old neighbors have closed down their businesses,” he said. He feels that some business owners have been targeted by potential buyers and been cajoled into selling their storefronts, but he has no plans of selling out. “Why would I leave? We struggled so much just to be here.”

Illustration by Daniel Rowell

Eleanore Catolico

Tutor at Daley College in Oak Lawn // 26 years old

Eleanore Catolico has lived in Pilsen for six years and works as a tutor at Daley College in Oak Lawn. She left her home state of Michigan in 2008 to attend DePaul University in Chicago, and Pilsen’s “strong community feel” attracted her to the neighborhood. Though she said her party days are behind her, she used to frequent Honky Tonk BBQ at 1800 S. Racine Ave., and she’s always trying new Mexican restaurants.

Initially, Catolico’s Mexican-American boyfriend introduced her to longtime residents and she has built good relationships with her mostly Latino neighbors on 19th and Laflin streets.

“I’ve never felt distant from anybody in the community, I’ve always felt open and invited,” she said.

Catolico is paying $800 for a one-bedroom apartment, which she acknowledges is high—she paid $500 for the same arrangement in Pilsen four year sago.

“It’s unfortunate that people are leaving the neighborhood, because Mexican families are what made Pilsen what it is,” she said. Catolico, a Filipina-American, hopes to see politicians step in to protect the remaining families from sharp rent increases.

Illustration by Daniel Rowell

Charlotte Phipps

Crossing guard // 43 years old

Every weekday morning and afternoon, Charlotte Phipps walks from her apartment on Ashland Avenue and Roosevelt Street to her post at the intersection of 18th and Allport streets. As a crossing guard for the Chicago Police Department, she ensures the safe passage of children and parents crossing the street, headed to and from school.

“I greet the families twice a day,” she said. “I say hello to the shop owners around me, and I’m getting to know the community.” When we spoke, she pointed to a mural that honors Miquita Ibarra, a neighborhood grandmother whom she knows personally and routinely helps to cross the street.

Phipps is in her second year on the job, keeping a close watch on the kids from St. Procopius Elementary School and struggling to understand why the Archdiocese is considering the closure of other Pilsen churches.

“This church is always packed, they’re always giving out food, and there’s always people driving by and doing the sign of the cross,” she said. On weekends, she has attended St. Procopius herself with her children. Locals love Phipps, and Phipps loves Pilsen right back. “It’s good people, mixed, and always popping.”

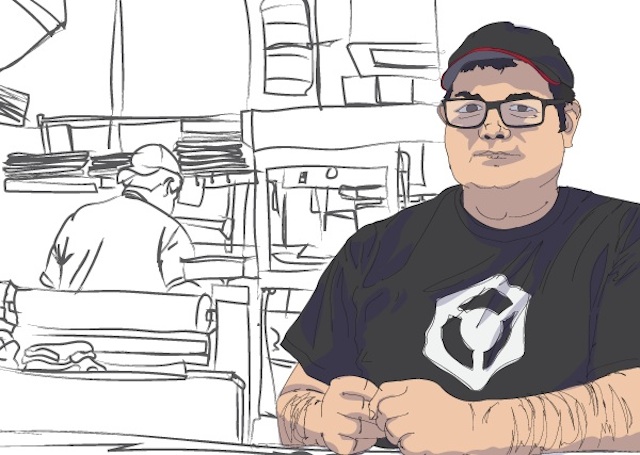

Illustration by Daniel Rowell

Enrique Salcido

Manager at Benny’s Pizza

Enrique Salcido answers the phone, jotting down pizza orders in Spanish and English, every four to five minutes throughout our interview, while also working the cash register. He’s been manager at Benny’s Pizza for almost 30 years. The restaurant’s 18th Street storefront, with its signature “Legend of the Volcanoes” Helguera-style mural, has a more old-guard sensibility than the shiny places popping up next door.

At 3 p.m., when we visited, customers in the pizza joint ranged from elderly Spanish speakers to hungry school kids in untucked white-and-navy blue uniforms. But in the evening, the scene shifts, particularly when “people across the street”—described by regular customers as young, boisterous gabachos (white people)—come in for a three-dollar slice.

“I can’t complain about the business,” said Salcido. He knows enough English to handle their orders, though he jokes that he needs to brush up on his language skills. “But it is sad that my people are leaving.”

In fact, Salcido left Pilsen himself. Three years ago he was paying $800 for rent in Pilsen, but found out he could become a homeowner in Midway for slightly more than that. Now, he has a mortgage, and has fulfilled the American Dream in that sense. But Benny’s and its regulars bring Salcido back almost every day, to answer the phone with a no-nonsense: “Benny’s.”

About the writer: Jackie Serrato was born and raised in the Southwest Side. She likes to observe the intricacies of the street through writing, audio and images. Her past work speaks to the experiences of the Mexican communities in Chicago, but she's developing a wider perspective about social issues in urban centers globally. She thinks street food is life.

About the illustrator: Daniel Rowell is a writer, illustrator, and bank shot specialist based in Chicago.