The Chicago Group Behind America's Best Documentaries Celebrates 50 Years

By Stephen Gossett in Arts & Entertainment on Jul 6, 2016 8:20PM

Violence interrupter Ameena Matthews with The Interrupters Producer/Director Steve James, Producer Alex Kotlowitz, and Co-Producer/Sound Recordist Zak Piper / Courtesy Kartemquin Films

“We come up with these catchphrases. I like to say, ‘We produce films that try to change society and the filmmakers that make them.’” For 50 years, Artistic Director of Kartemquin Films Gordon Quinn has succeeded in that grand ambition. The Chicago-based documentary house’s most famous achievement, Hoop Dreams, was called the best American documentary of all-time by Roger Ebert. Various other filmography highlights—Chicago violence-prevention study The Interrupters, nun-on-the-street interview Inquiring Nuns, and local labor-conflict chronicle The Last Pullman Car, among many other come to mind—also set a lofty standard for socially conscious nonfiction filmmaking.

Perhaps Kartemquin’s most impressive feat over those five decades has been that from day one it has never wavered in its dedication to social justice, even as trends in documentary filmmaking have evolved. Kartemquin's films largely chart the path of modern documentary filmmaking, extending from cinéma vérité through to the contemporary “advocacy” doc. Yet time and again they manage to avoid the pitfalls common to each school. Non-purist means in service to the purest intentions.

It began in 1966 at the University of Chicago with three student co-founders, Quinn, Jerry Temaner and Stan Karter, and one fantastically cornball art-house pun: Kartemquin is a portmanteau of their last names and also a nod to Battleship Potemkin, Sergei Eisenstein’s 1925 silent classic. (The late Jerry Blumenthal joined shortly after, “but they weren’t going to change the name to Kartemquinthal.”)

The group was enamored with the emergent cinéma vérité movement, in which filmmakers like D.A. Pennebaker and Jean Rouch embraced an unobtrusive approach. They desired their films to simply observe their subjects and largely eschew imposed narratives or abstract, experimental flourishes.

“That’s what really excited us,” Gordon told Chicagoist. “[Pennebaker’s] Happy Mother’s Day, [Rouch’s ] Chronicle of a Summer. We were really influenced by those films that we saw in the early ‘60s. That’s where we were headed.”

But for Kartemquin aesthetics were inextricable from politics from the very beginning. “I wrote my BA paper on cinéma vérité and democracy. I was very influenced by the work of liberal philosopher John Dewey. So we were looking for a way to create an organization that could create media that would engage with the democratic process. Something that would help people see across various kinds of class, racial and economic lines to tell different kinds of stories. We had all been very influenced by the civil rights movement.”

The key sense of community solidified when Kartemquin moved north from Hyde Park and entered its self-described collective era. Quinn and Blumenthal had joined with activists from the Women’s Liberation Union and the Women’s Health Movement on a story about the fight to save a 75-year-old home-birth service. The Chicago Maternity Center Story (1976), a mid-period triumph, explores still-all-too-relevant subjects of corporate overreach and underfunded women’s-health facilities. The necessary personal dimension and sense of clear, crafted point-of-view that would help make masterpieces like Hoop Dreams so broadly appealing is present, too.

Still from The Chicago Maternity Center Story

“In a year we had evolved into a group of 12 or 13 people reading Mao and making films that were not so purist in their vérité,” said Quinn. “They had a driving narration. Even though they were character-driven, we also provided a great deal of analysis for the viewer. We came to understand you can’t just reflect society back onto itself to make social change. You also have to look at the power relationships within society to really engage with the democratic process.”

The relatively underpraised films that immediately followed—particularly The Last Pullman Car (1983), Taylor Chain (1984), Golub (1988)—prefigure the exemplary run of what you might call the Steve James era: embracing the journalistic diligence, but never forsaking social justice point-of-view for the sake of an imagined supreme objectivity. They boast a slightly more firebrand charge than subsequent work, too. But the effect is one of clear-throated urgency, rather than didacticism.

“It’s not preaching to the converted, it’s trying to make an analysis that is really useful for people who are on the ground trying to change things,” said Quinn. “People involved in a social justice struggle have to understand what they’re up against—the historical and economic context in which the struggle took place. They had a polemical quality but the purpose behind them was to create films that would engage.”

Chicagoist just dove deep into the legacy of Hoop Dreams here, but it must be said that the commercial and artistic breakthrough cemented Kartemquin both in the canon and as an operational unit. “One of the things that changed with Hoop Dreams, we had the ability to make films that were going to be able to reach out to people who weren’t necessarily attuned either to the people or the issues we were talking about.”

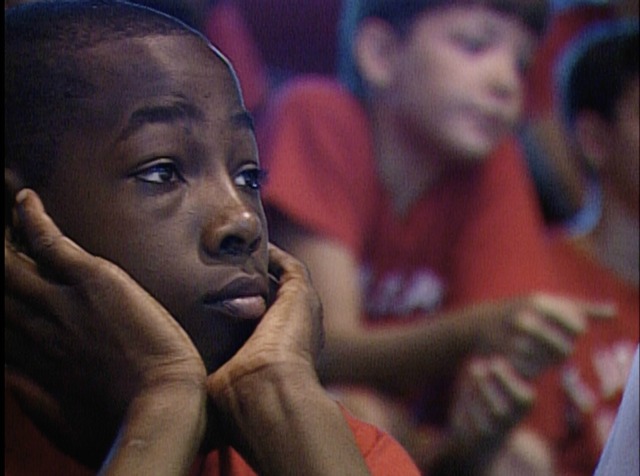

Arthur Agee in Hoop Dreams / Courtesy Kartemquin Films

The non-profit was also able to formalize the once-informal collective instincts on which it built the foundation. In the 70s, people from different walks of like—union workers, activists, educators and filmmakers—converged to “skill-share.” Today, that same spirit animates one of the most robust non-narrative filmmaking internships in the country and also the semi-legendary KTQLabs, monthly critiques where filmmakers, often beyond Kartemquin’s internal sphere, receive feedback. (Workshopped titles include Making a Murderer, Louder Than a Bomb, and Andrew Bird: Fever Year.) The youth-mentorship program Diverse Voices in Docs, run in conjunction with the Community Film Workshop on the South Side, is just the most recent example.

If it weren’t already clear, Kartemquin’s deep Chicago roots remain central to its character. Early on, they were tempted by public-TV powerhouse WGBH to move to Boston but made a conscious choice to plant flag here. “We made a commitment to Chicago and the Midwest. We always felt regionalism is important to a big democracy.” Quinn cites two recent opuses, the seven-hour immigrant-experience chronicle The New Americans and the six-hour duPont-winning Al Jazeera America collaboration Hard Earned, which each incorporate a tale from the Chicagoland area. “It makes a difference where you are. We make films all over the world, but we do see ourselves as bringing Midwestern stories to an international audience.”

Check out the full calendar of Kartemquin 50th Anniversary events here, including the weekly Kartemquin Summer Films Series at Doc Films, public-television broadcasts, and an outdoor screening of Inquiring Nuns at Millennium Park on July 26, among others.