Meet The Man Behind Chicago's 1979 Disco Riot And His Biggest Critic

By Stephen Gossett in News on Jul 12, 2016 4:31PM

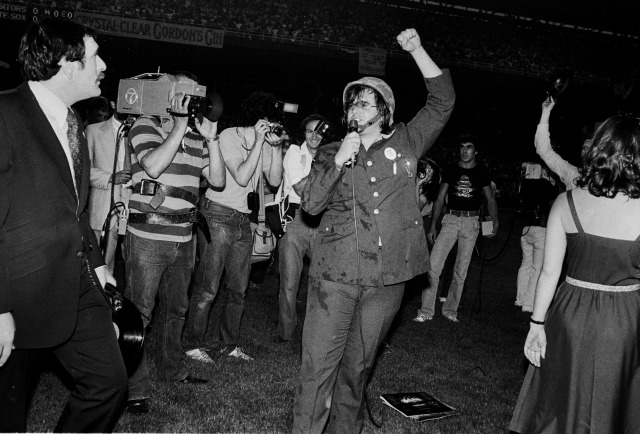

Photo: Paul Natkin / Courtesy of Curbside Splendor

It was 36 years ago today that one of the most notorious moments in Chicago sports and music history went spectacularly off the rails.

It would have been a routine doubleheader between two then- (and now-) mediocre baseball teams—the Detroit Tigers and the hosting Chicago White Sox—if not for two men: promotions manager Mike Veeck, son of legendary White Sox owner/gimmick aficionado Bill Veeck, and local novelty DJ Steve Dahl, of 97.9 The Loop. Dahl, who had been replaced by a disco format at his previous gig, was fomenting an anti-disco revolt at his new station. Their scheme: a ticket to the two games would cost 98 cents and one disco record. The collected vinyl would be ceremoniously exploded on the field after the first game.

The true nature of the pandemonium that ensued—a massive rush onto the field by a large portion of the estimated 50,000 attendees, fires in the stands, at least one maniac sliding down the foul pole—depends on who you ask. It was either a relatively innocent flying of the rock ‘n’ roll freak flag, or a ritual destruction of gay and black culture. Or it was both. Photos show gawky hesher dudes who look like extras in a Richard Linklater period piece; and they also show a fair amount of damage, left to be fixed by a predominantly black field crew. Thirty-seven years have only complicated the question.

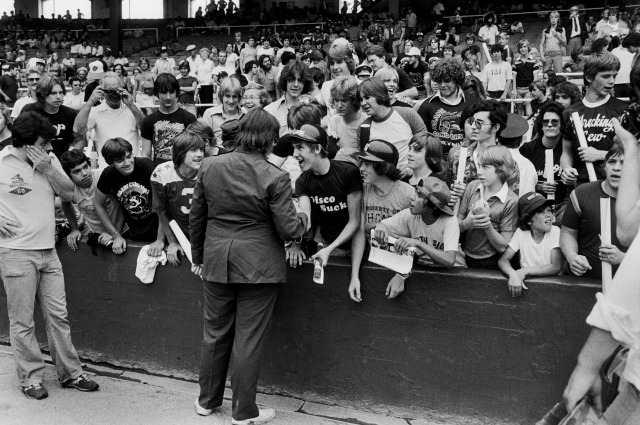

Photo: Paul Natkin / Courtesy of Curbside Splendor

Disco Demolition, a new book written by Dave Hoekstra with the cooperation of Dahl and published by Chicago-based Curbside Splendor, enters the fray with a wide-ranging collection of interview subjects culled from baseball, rock, house music and other, more unexpected corners. Opinions expressed are primarily, though not uniformly, Dahl-sympathetic, and some critics have reacted negatively. Tal Rosenberg of the Chicago Reader wrote “the book reads as overt hagiography.” And while this writer was critical of Dahl while disagreeing with that conclusion, I agree with Rosenberg that more diverse voices would have been an improvement. With that in mind, I reached out to house-music pioneer Vince Lawrence, perhaps the book's greatest omission, and followed up his critical perspective with Dahl himself.

Lawrence co-wrote “On and On,” one of the foundational tracks of house music—a genre of dance music born in Chicago, rising out of the ashes of disco. But years before that, Lawrence, who is black, was a 14-year-old usher at old Comiskey, and he was present at Disco Demolition. It’s fair to say his recollections fall outside the “freak-flag” narrative.

In a 2001 BBC documentary called Pump Up the Volume: The History of House Music, Lawrence notes that stadium-goers weren’t bringing just disco records, but records by random black artists in general:

"It was more about blowing up all this ‘nigger music’ than, um, you know, destroying disco. Strangely enough, I was an usher, working his way towards his first synthesizer at the time, what I noticed at the gates was people were bringing records and some of those were disco records and I thought those records were kinda good, but some of them were just black records, they weren’t disco, they were just black records, R&B records. I should have taken that as a tone for what the attitudes of these people were. I know that nobody was bringing Metallica records by mistake. They might have brought a Marvin Gaye record which wasn’t a disco record, and that got accepted and blown up along with Donna Summer and Anita Ward, so it felt very racial to me.”

(Metallica did not form until 1981 but his point is well taken.)

Lawrence told Chicagoist he “absolutely” still feels the same way today, finding a corollary between Dahl’s “speaking in code” rhetoric and today's “xenophobic” political landscape.

Screenshot of Vince Lawrence in Pump Up the Volume: The History of House Music

Lawrence actually requested to work the night of Disco Demolition, and had previously listened to Dahl on the radio. He was even sporting a Loop t-shirt underneath his uniform. “I wanted to see [Dahl’s band] Teenage Radiation. I liked that; cool name. But they didn't play."

The game experience was very different from what he expected. He recalls someone breaking a Marvin Gaye record in his face and saying, “How do you like that?” Recollections like this belie Dahl’s vision of himself as victim of revisionism, which Lawrence calls “delusional.”

“Revisionist history? I was freakin’ there," Lawrence said. "I was on site. That’s not revisionist. I experienced it! Why did he do that to me and not the 50 other people who were within a few feet? Crazy.”

As for the refrain about kids just blowing off some steam? “That’s what Brock Turner’s dad said about that idiot.”

It’s a stern criticism; and Dahl responds with a conciliatory tone—arguably a more conciliatory tone than is demonstrated in Disco Demolition. “I certainly regret that that happened to him,” Dahl told Chicagoist. “It was never my intention to have anybody do anything like that. But I can’t control everybody—I couldn’t control anybody that night as it turned out. Nobody was more surprised than me it turned out the way it did.”

I put forth the idea to Lawrence that perhaps Dahl was reacting against disco’s mainstream doggerel—your “Disco Duck”s and “YMCA”s— the wrong side of the “popular plague vs. mystery cult” divide common in disco histories.

“I just think that’s bullshit. Look at the top records of 1979. I bet there are a lot of records other than one or two cheeky mainstays of the chart.” He has a point. Canonical cuts scatter the top ten: "Bad Girls," "Le Freak," "I Will Survive," "Hot Stuff," "Ring My Bell." Number one is a rock cut, the Knack's “My Sharona,” but Lawrence’s crowd loved that, too. “We were playing the Knack at parties! I won’t go so far as to say we were playing "Good Girls Don’t." But we played the Knack.” His point is clear: disco-vs-rock was always a false choice.

But rock kids felt marginalized by the demands made by saturation-point disco, according to Dahl. “It came down to People magazine and most of pop culture indicating to kids in t-shirts and jeans if you wanna get laid, you have to put on a white three-piece suit and get into a disco and dance.” Dahl points to the potent combination of youth, identity and music as potential grist. "When you’re in your ‘20s and you identify so heavily with music, some people felt disenfranchised by that. I never felt threatened by disco. I was really just trying to lampoon something I thought was pretty puffed up and silly.” Plus the Loop audience’s preferred brand of AOR rock was itself relatively young, far from being the immortal “classic” rock it became, he adds.

But the interpretation of “Disco Sucks” backlash as working-class, anti-elitist crusade holds no water for Lawrence. “Black people in Chicago were going to disco parties in droves; and the average black person was not a rich guy. So Dahl describing the attire, saying he’s allergic to gold jewelry, feels like pointing the finger at black culture. Gold chains were a symbol of black success, a middle finger to our oppressors: now we’re in chains willingly.” He draws a parallel to the Lucky Strike dress-code controversy of 2010. “You draw a circle around black culture.”

Dahl maintains that was never the intent and also disputes Lawrence’s chronology. “If you look back at Saturday Night Fever, all those guys had gold chains. The timeline doesn’t match up with the narrative. It just doesn’t. That was never anything that I thought. Back then, to me in Chicago, it was the Italian snaggletooth necklace—that was the comedic target."

Despite Lawrence’s critique, driven by personal experience, Dahl contends that accusations of racism and homophobia against Disco Demolition are a “fairly new phenomenon,” directed from outside in. “I understand how people can see it that way today. We evolve as people, as a society. But it never crossed my mind. I’m not racist or homophobic. By that logic I should have blown up Jimi Hendrix, Chi-Lites and David Bowie records. It was really disco-phobic. It’s complicated but those were also simpler times. Whether right or wrong, that’s the way things were.”

Lawrence is quick to forestall potential cries of over-sensitivity, pointing out that he’s lived an integrated existence his whole life. “My wife is white. I went to an integrated high school [Whitney Young]. I’m accepting of all sorts of people. You have to dig in pretty deep to make me feel that way. If I came to that objective conclusion, a lot of people could. If Mr. Dahl was insensitive to that fact, that was a choice he made.”

Photo: Paul Natkin / Courtesy of Curbside Splendor

To be sure, many disco histories are similarly skeptical, especially when weaving in the broader social climate. In Turn the Beat Around (2005), author Peter Shapiro invokes Chicago’s silent-majority white ethnic population when tackling Disco Demolition. “Dahl’s disco riot was emblematic of the politics of resentment of the white everyman that would enable the 1980s conservative revolution,” he writes.

The nexus between Dahl’s “riot”—should you accept Shapiro’s context—and today’s hostile political climate is pretty irresistible. Shapiro's historical framework posits the white Midwestern male, circa 1979, as, above all, rendered impotent by industrial decline, dependency on foreign oil, and humiliation at the hands of a Muslim menace (by way of the Iranian hostage crisis)—all of which is difficult to read today without thinking one word: Trump.

Disco Demolition arrives at a more charitable conclusion—unsurprisingly, considering Dahl’s involvement—but it nonetheless contains thoughtful criticism from some of its interviewees. House-music veteran DJ Lady D, who played records at the book-release party, says in the book,“[Aspects of racism and homophobia] may have not been Steve Dahl’s mind frame at the time, but it came from somewhere. And it reverberated. Energy in, energy out.” Metro and Smart Bar owner Joe Shanahan is particularly critical. The book is also upfront about Bridgeport’s history of racial tension. Former White Sox player Thad Bosley, who is black, recounts having his car threateningly circled by a group in the neighborhood before someone recognized him and directed him to safety.

Dahl told Chicagoist he was unaware of Lawrence and his experience until just a few days ago, otherwise his point of view would have been included. Still, since Disco Demolition so scorned disco for its exclusionary aspects, its orchestrator should be extra diligent to not exclude perspectives like his.