A Reformed Neo-Nazi Talks Trump, Mt. Greenwood & White Supremacy

By Stephen Gossett in News on Nov 28, 2016 3:40PM

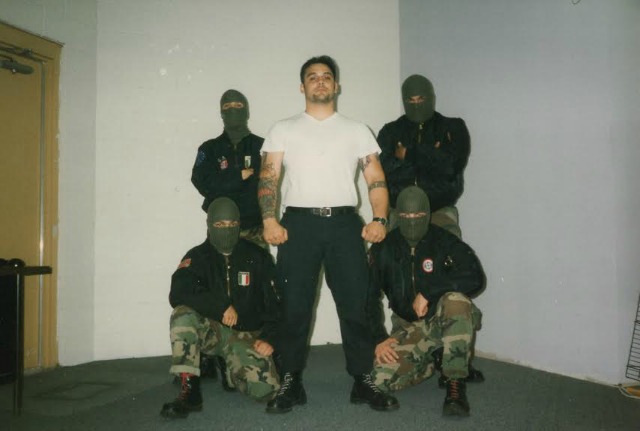

Christian Picciolini (center) with his former band, Final Solution / Courtesy of Picciolini

Hate is taking its close-up right now.

Reports of hateful intimidation since the election number above 700; across the nation, we’ve seen a wave of racist and xenophobic vandalism; and participation swelled at last week’s National Policy Institute conference, Richard Spencer’s cosmetically scrubbed-up iteration of white nationalism. The fulcrum point—whether stated or unstated—is Donald Trump, who has embraced InfoWars-style, coded nationalism-speak and appointed Steve Bannon, former head of Breitbart News, as chief strategist. His response to the extreme right has ranged from stammering non-disavowal to worryingly tepid. All the while, mobilization among hate groups, both traditional and diffuse, has spiked.

Chicago played its own lamentably key role in the development of the modern hate movement. One of the very first organized neo-Nazi skinhead movements in the country was birthed here, in the late 1980s. The Chicago Area Skinheads (CASH), which grew out of Blue Island, just south of Chicago’s southwest border, was responsible for a wave of racist attacks during its heyday, including firebombings, vicious assaults, and numerous acts of vandalism against synagogues and Jewish-owned businesses.

At the age of 16, Christian Picciolini, became head of CASH, after its founder, Clark Martell, the man who recruited into Picciolini into white supremacy, was sentenced to prison. Now reformed and branded a “race traitor” by his former associates, Picciolini today leads pro-peace public talks with groups such as the Anti-Defamation League and works to combat right-wing extremism with his groups Life After Hate and Exit USA—which seek to educate and pull people away from white supremacist groups. His memoir, Romantic Violence: Memoirs of an American Skinhead, was published last year.

We caught up with Picciolini to talk about the mainstreaming of hate, the new-but-familiar face of white supremacy, his alarming experiences at last fall’s Trump rally protest and how the legacy of racial tensions on the Southwest Side—including Mt. Greenwood—has been stoked by white nationalism for decades.

Chicagoist: How much of the current mainstream political environment rings familiar with the white-power underground circles of Blue Island you trafficked in in the '80s and '90s?

Christian Picciolini: Quite a bit actually. 30 years ago in white supremacy, we had a strategy called leaderless resistance. The concept was: stop shaving our heads, stop getting tattoos and instead try to blend in as much as possible. It was a really concerted effort to try and tone down the rhetoric and make it a little more palatable to the mainstream. And it certainly has penetrated the mainstream now. We’re seeing people who were supportive of our cause back then also supportive of Trump’s cause, certainly with the recent cabinet appointments. It’s a cause for great concern because a lot of these people have said and done repulsive things in terms of racism and misogyny and marginalizing people—it’s really come to fruition, something I’ve spent the last 21 years of my life trying to expose and educate people on. This really is kind of a dream scenario for white nationalists at the moment.

I can say from personal experience, I was at the cancelled Donald Trump rally in Chicago—where, by the way, I didn’t see any violent protesters—but when I was inside in the UIC Pavilion and I heard some of the most vile things come out of people’s mouths, more vile than I heard at any Klan rally or the dozens neo-Nazi skinhead rallies that I’ve been to. There was a woman going throughout the whole stadium, pointing out people of color and urging security to remove them because they were protesters. She had no way of knowing if they were protesters; they were just seated quietly. Security would come and escort them out. To me that’s a major red flag.

Christian Picciolini

C: Do you know if any of the people from the old Chicago Area Skinheads movement of the '90s became actively involved in the Trump movement? And do you see a corollary between the two?

CP: I’m not in contact really with people from CASH and couldn’t say who they now support politically, but I can tell you through my research online over the last four months, in which I’ve been doing interventions with people who are part of hate groups, that I’ve discovered essentially thousands and thousands of pro-Trump neo-Nazi accounts.

When I was on an intervention in Florida three months ago, through my research on that case specifically, there was an underage girl making pro-white, national-socialist propaganda videos—she was a big Trump supporter. A boyfriend she had, supposedly a 23-year-old guy from Boise, was writing scripts for her. I found out he wasn’t who he said he was, this girl was being sort of catfished. But this guy had essentially created thousands of pro-Trump bots spreading wild misinformation and propaganda. There are a lot of people being duped with misinformation, and they’re all rejoicing over Trump. And having a white nationalist be his chief strategist and have a racist be your attorney general, this is a really dangerous situation for our country right now.

However, there are also people not being necessarily influenced by this misinformation, that still choose to support racist rhetoric because they feel white dominance in America is slipping through their fingers. To them, "diversity" is a codeword for white genocide. They claim that their "homelands" are being overrun by minorities and are desperate for solutions that ensure their "white survival." This fear, of course, is irrational and solely based on a loss of white power and control.

C: There’s been a mixture of shock after the election but also a sense of, What did you expect? We know racism runs deep in America. Are you surprised?

CP: I can’t say I’m surprised. I’ve been doing public speaking engagements and for the last three years, I’ve been warning about this very scenario. For years now, I’ve been talking about the rise of the extreme right in the U.S. Since 9/11, white nationalists have killed more Americans on U.S. soil than any foreign or domestic terrorist group combined. It’s something we don’t categorize as terrorism or extremism. We often brush it off as mental illness—things like Oak Creek Wisconsin—and these people are certainly tied to white supremacy, have written manifestos. We’ve got a major problem in not calling that terrorism.

Certainly the election brought that to the surface for people that didn’t expect it was as large as it is. But hate crimes have increased since the election. So I’m not surprised. I’m hopeful, very vigilant. We’re seeing the same thing as what happened in 1933, when a politician stokes fears and grievances to rally them for a nationalist cause. But nationalism to the exclusion of other people is not nationalism, that’s xenophobia.

C: You’re an example of someone who was a racist, but changed. But at the same time, I don’t—and most people don’t—have much appetite for empathy for bigots. It feels like a Catch 22.

CP: It is a bit of a Catch 22. We try to approach everything in Life After Hate and Exit USA with compassion. While we really promote approaching things with compassion and empathy, because that’s what changed us, it’s very difficult knowing there are very virulent, vile people who are focused on furthering the Trump cause. Right now we’re dealing with a lot of fake news, misinformation, propaganda, parody. My goal is still trying to reach people through compassionate means, and to get them access to real information. My goal is to share my story and get people out of their bubble, so they can empathize. I received compassion from the people I deserved it least from when I least deserved it, and that helped change me. When you take fear and isolation and put grievance on top, it’s all too easy for people to hate and blame somebody else for their problems.

Courtesy of Christian Picciolini

C: You grew up in Blue Island, just a stone’s throw from Mt. Greenwood, which has become a flashpoint of racial tension this month after a black man was fatally shot by an off-duty cop. It also has had a long history of segregation. Can you talk about your experiences in that region, then and now?

CP: Those are my old stomping grounds, Mt. Greenwood, Blue Island, Beverly. Those were the places I recruited the most 30 years ago, where a lot of our members lived, and where we did a lot of our business. Of course it’s no surprise to me Mt. Greenwood is one of the places where a lot of white cops and firefighters live because they need to maintain a Chicago address. They’ve concentrated in those areas because they view them as the last white bastions of Chicago. It was always a very self-isolated neighborhood surrounded by diverse neighborhoods. They’ve maintained their white status by being racist, limiting the amount of minority-owned businesses. It’s a dangerous situation when you build a wall around your community because you reinforce polarization. While Beverly has grown in diversity, the latest attack in Mt. Greenwood is really an indication of what’s been happening for decades. With presidential politics and misperceiving Black Lives Matter, it’s thrown gasoline on sparks that have already existed.

C: You mentioned law enforcement. Do you know anyone in law enforcement who did or does have ties to white nationalism?

CP: There were a lot of people in our group who went on to become cops and firefighters and correctional officers. Unfortunately so. I haven’t talked to them in 20 years, but just by keeping tabs on Facebook I know that there are some who’ve gone that way. And they’ve never indicated publicly that they’ve changed their opinions. It’s a minority. I know a lot more people who do social justice in those lines of work than people who were part of my white nationalist organization at the time.

C: What’s that region like now, in your mind?

My family still lives in that area. Blue Island has gotten more diverse. I can’t say I’ve seen any formalized white supremacy grow. I was a selfish leader and never trained anybody to train over my group. It scattered when I left. But Chicago has always been a very segregated city and Mt. Greenwood is an example of that. I can’t say I’ve seen organized white-supremacist growth, but I have seen racial tensions increase. I think we’ve all seen that. In the last eight years, especially, the far right has considered diversity a code word for white genocide.

We’ve seen hate groups rise across the country. But we’ve also seen an increase in the average person, who looks like your doctor, your lawyer, your mechanic, your dentists, starting to say the same types of rhetoric. Sometimes it’s a little bit more polished, something the average person who has underlying racism can attach himself to. I’m less concerned about skinheads and Klansmen now than the average person who feels emboldened, and the militia and sovereign-citizen groups who are certainly tied to white supremacist organizations, training in paramilitary camps. As far Chicago, our city was designed with racism in mind, with neighborhoods segregated by expressways and train tracks. Even suburbs, like Highland Park, have long histories of barring Jewish and black people. That history that has always existed has come out of the shadows because of the social and political climate.

C: Is there anything in your work that gives you hope in such a dark time?

CP: I’ve been flooded in the last few weeks for support from people who found our organization who’ve say, “I’ve never been an activist, but what can I do?” That’s really encouraging. People are ready to be actors in making the world a better place. On the flip side, I’ve received death threats and trolling from people on the opposite end of the spectrum. But I’m hopeful because people are ready to step up and educate people, support peaceful protest, and make their voices heard. People are motivated to make a positive difference.