Interview: Wallace Shawn

By Rob Christopher in Arts & Entertainment on Sep 8, 2009 5:20PM

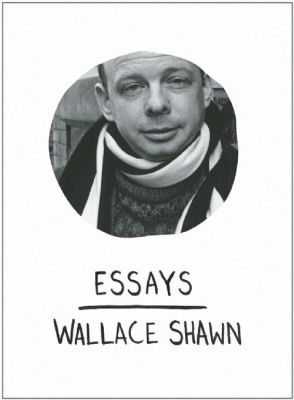

"I suppose I should say that all my roots are all in Chicago," Wallace Shawn told us. "Both sides of my family. My parents were very identified with being from Chicago, really. My childhood memories of visiting the relatives in Chicago are central to my being. And all sorts of things that some people associate with New York, I associate with Chicago, like going to hear jazz. I went with my uncle to hear Erroll Garner in Chicago." Shawn is usually thought of as the quintessential New Yorker (in fact his father William was the long-time editor of The New Yorker) but his new book is published by Chicago-based Haymarket Press. Essays is Shawn's first all-nonfiction collection, with pieces about the theater and writing, and impressions of living in post-9/11 America.

"I suppose I should say that all my roots are all in Chicago," Wallace Shawn told us. "Both sides of my family. My parents were very identified with being from Chicago, really. My childhood memories of visiting the relatives in Chicago are central to my being. And all sorts of things that some people associate with New York, I associate with Chicago, like going to hear jazz. I went with my uncle to hear Erroll Garner in Chicago." Shawn is usually thought of as the quintessential New Yorker (in fact his father William was the long-time editor of The New Yorker) but his new book is published by Chicago-based Haymarket Press. Essays is Shawn's first all-nonfiction collection, with pieces about the theater and writing, and impressions of living in post-9/11 America.

He's a man of many roles, including actor, most famously uttering the line "Inconceivable!" in The Princess Bride. But it is as playwright that he's most impressive. His plays are all calculated for maximum discomfort: they deal with disturbing subject matter (sex, cruelty, genocide) and often take the form of long monologues or are performed without intermissions. Most brilliantly, they're couched in the most polite language possible and are often hilarious. Just imagine Henry James rewriting "Springtime for Hitler."

Shawn is unusually visible these days. Earlier this year London's Royal Court Theatre staged a Wallace Shawn festival which included his new play. Criterion recently released a beautiful edition of My Dinner with Andre; and Marie and Bruce, starring Julianne Moore and Matthew Broderick in the film adaptation of his play, recently appeared on DVD. We talked with him recently about politics, the future of newspapers, why so many people hate his writing, and the early 80's.

Chicagoist: I'm wondering how it came to be that you published the book with Haymarket rather than a New York publisher.

Wallace Shawn: I have a friend, Anthony Arnove. I don't know if he likes my writing because he's a friend or if he's my friend partly because he likes the way I think. But he had the idea. He and his girlfriend, Brenda Coughlin, told me, "We like the way you think, and you should collect your essays into a book." And Anthony is not merely a friend, he also works at Haymarket, as well as doing a hundred other things. And so he said, "We'll publish it." So it was originated by him.

C: Because the pieces were all written under a bunch of different circumstances over a number of years, what was it like putting them all together and seeing them juxtaposed? Did you have any surprise revelations seeing them all in one place like that?

WS: I suppose I was surprised that they almost all refer to The New York Times. I don't know, I suppose that's all but inevitable for someone who lives in New York.

C: One of the things I noticed is your sort of love/hate relationship with The New York Times. It seems on the one hand you sort of seem to crave its presence as a daily habit in your life, almost like a drug that you're dependent on, but on the other hand you're sort of sickened by its self-importance and its sense of detachment from what it's reporting.

WS: Well, I don't read The New York Times in a public place, for example, in a restaurant, because I'm afraid I might be setting a bad example. But I have never been able to fully break my addiction to it. And now that it is threatened with extinction like other newspapers, I suppose I do recognize that I have to admit that every once in awhile they allow some reporter to spend a long time working on a fantastic story that brings out some facts that otherwise would have been buried forever. But the complacency of The New York Times as a sort of thought balloon of the ruling class of the United States is sort of repugnant to me.

C: Do you have other things you read as a sort of counterpoint to The New York Times?

WS: Although it's not that easy to obtain in my neighborhood I very, very frequently read The Guardian from England. And of course as one might have imagined I read The Nation. And I listen to Democracy Now! on the radio. I read Doug Henwood's Left Business Observer and Alexander Cockburn's Counterpunch. Tom Engelhardt has an incredible website that collects fantastic articles. But obviously it's true that newspapers find facts and have great resources to do so. It's terrifying to think there might not be newspapers.

C: Do you think you would be getting more of your news online then if something happens to The New York Times?

WS: The question that people are concerned about is whether the online--let's say there was only an online version of The New York Times. Would they have the cash to send people out and really do investigative reporting? Would they be able to send a correspondent to different countries? Not to become too involved in sentimental nostalgia, but the old New Yorker wrote these very, very long factual articles that a lot of people, including me, learned a great deal from.

C: It had the room and the space and the passion for that kind of stuff.

WS: It was not really replaced. When The New Yorker abandoned that practice of writing such long articles nobody else exactly came in to take its place. That was it, which is sort of an incredible fact. It's true though.

C: I think a lot of that has gone to the online world. Yet it seems there's so much online that one's attention span is cut down and you don't have the patience to sit there and read a long piece or a long series of pieces like that. It's just all a bunch of little short pieces you can link to.

WS: Yeah. Obviously, a person who is good at it can learn a staggering amount of information from the internet. A person who is mediocre or bad at it probably can't. But there are stories that can only be reported by a reporter who goes to the place and interviews people. And the question is, how many of those people are there going to be? Who's going to pay for that?

C: A large chunk of the essays in your new book were written around the time of 9/11 and during the depths of the Bush years. Now, Obama is in the White House. Do you think things have changed, or at least made change possible? What do you think is happening? What's the difference?

WS: Well, you know, anything that we say today about the Obama presidency will probably look silly in three years. It's just the beginning of his presidency. He's certainly made many statements that Bush never would have made, and God bless him for that. But so far his actions seem cautious. To me the basic position of the United States was very, very appalling. To change that only cautiously means that I find the situation still very, very appalling. I'm horrified by so much of what seems to be happening. Expanding the war in Afghanistan seems crazy. The rather pitiful steps towards an improved health care system that Obama seems to feel are the best he can offer are sad. The United States has not really changed dramatically since Obama became president except that if he follows through in action over these next few years on some of the rather wonderful things he's said, then maybe he will have made a very important difference. The group of people around Bush were grotesquely brutal people, and their concern for the suffering of humanity seemed to be minimal. So it is a fantastic thing that they're not the leaders of our nation anymore.

C: Do you think that was just an extended moment of rottenness, or were things always that bad and we just didn't pay attention?

WS: Unfortunately when people have power they often use it to entrench themselves and the United States has been terribly powerful since the end of World War II. The United States has been incredibly powerful and has used its power very harshly and brutally and killed a lot of innocent people in order to preserve the American status of living and the status quo. And of the presidents we've had, Bush was the one who most openly exulted in that, shall we say. He certainly wasn't the only one to practice it. We overemphasize the individual leader in our discussion of politics anyway. It's a kind of craziness to think of these individuals.

C: Because there was a whole package that came along with Bush. If Bush was just a terrible president, that'd be one thing. But when he came into power there was a whole bunch of his friends and colleagues that came in there as well.

WS: Absolutely. But beneath even that layer you have to say there's some kind of a system going on which is a little bit harder to analyze, but it isn't just about individuals.

C: A lot of the essays in the book are very political but of course there's a lot about the theater. I thought I would switch gears just a little. I just managed to finally see Marie and Bruce, the film.

WS: Really?

C: Because of course it never made it to Chicago, at least as far as I know.

WS: Or anywhere else.

C: I saw the film and read some of the reaction to it, and I'm just really shocked by how vicious the comments tend to be. I was looking on Netflix today and, at the risk of being depressing, they range from "pretentious," "gloomy," and "disgusting," to "pointless at best." I really enjoyed the film, but why do you think people are so disturbed and offended by this movie?

WS: I think it's a wonderful film. I have to say that most people don't like my writing and those who do like it have to basically--most people who like my writing have somehow been tricked into exposing themselves to two or three things by me. Usually the third one does the trick. It seems that the first thing of mine they see, they say, "Well, that was awful," or "disgusting" or whatever. And the second one they think, "Well, that's a little bit better." The third one they think, "Well, now maybe this one is good. This one is not so bad. These two others were awful but this third one is actually not so bad." It doesn't matter what order, it's usually the third one that people begin to appreciate. Of course, why would anyone get to the third one if they found the first pointless or whatever? I once knew an astrologer who said that no one who has fully learned the system of astrology doesn't believe it. Which is undoubtedly true. But no one would study the entire system of astrology unless they were at least somewhat convinced that it might be true. I don't what to say. I've been writing for forty years and most people don't like what I write. But then there's some people who do. Most of the people who would have seen Marie and Bruce have never seen anything else by me, because it's just a movie that comes out. As far as they know, it's just meant to be a regular drama or a regular comedy. Well, it isn't at all. It's one of my strange plays. People who are familiar with my plays think it's a terrific movie, but people who have never heard of them very frequently have thought, "Well, hang on a minute. People don't actually talk like that. This is terrible dialogue! My three-year old could write better dialogue than this, it's not realistic at all!" They're thinking in the wrong way about it.

C: Right, they're thinking, "Oh, it's Julianne Moore and Matthew Broderick--"

WS: "--and why didn't someone write this in the normal way?" To them, it's just plain bad. They're shocked that such bad writing could be--why did these good actors get involved in that?

C: Even though the movie wasn't done as a period piece the play itself taps into a very particular kind of 70's New York atmosphere. What do you remember most about that time in New York?

WS: I suppose 1980, the year that Marie and Bruce was first done, that year did mark a huge change in New York because that was when Reagan came in and there began to be homeless people living on the street. Before that there were not people living on the street; or, I had never seen one, except in India. And yuppies appeared. People who were interested in food, and good living or something. I do remember when food came in. Everybody was suddenly taking about food and cooking when previously, if you can imagine, such a thing was not really a topic of interest or discussion. I mean, there may have been super-sophisticated people who knew about it. But I didn't know about it. I thought either you could have steak or chicken, or if you wanted something different you could go to a Chinese restaurant. The idea of everybody reading about different ways to prepare food in the newspaper was new.

C: And now Julia Child is on the top of the bestseller list for the first time.

WS: Yes!

C: Michael Pollan said the more we read about food and watch television shows about food, the less time we actually seem to be spending in the kitchen. So it's like food has become a spectator sport.

WS: Yeah! I know that he believes that people should cook together and it should be something of a ritual.

C: I wanted to ask you about The Hotel Play. It's one my favorite plays of yours just because it's so audacious. [note--the play has been very seldom revived because it requires a cast of 70-80 people] Do you have any idea how many times it's been staged as it was written with the full cast?

WS: Well of course, never professionally because it's too impractical I suppose. I just saw an incredible reading of it in England which had 65 people in it. And I know it's been done in the university setting on several occasions. But not too many people have taken it on. It's never been done for a paying audience, as far as I know. Well now, actually, when we did it at La Mama in '81 it was for a paying audience. It was for three weeks. Actors' Equity gave us a special dispensation. It had an audience of 99 and a cast of about 89. I don't know--you had to pay like $10 to see it or something.

C: It seems like that's the biggest scale you've ever worked on. Most of your other pieces tend to be more intimate, chamber affairs. Are those just the kinds of characters you hear speaking to you? More intimate?

WS: I suppose that's the way that most contemporary plays are written. Ibsen usually doesn't have more than eight or nine people in a play. I don't know--if you want to have a thousand people you might consider doing a film.

C: Have you ever had any desire to write an original screenplay? I mean, My Dinner with Andre was an original screenplay, but that's very much the exception to the rule. You haven't gone back to that. Do you ever get an idea that feels like it would make a better film than a play?

WS: I would find it very frustrating to write something that would not be done. That is a barrier. Because with film, you run the risk that it might not be done. Although today you can make a film more cheaply it still doesn't seem to be that cheap.

C: And it's still harder than ever to actually get it shown.

WS: Oh, to get it shown is impossible.

C: So there must be some sort of switch in your brain that's saying, "Well, I think I'll do another play because I know it'll get staged somewhere."

WS: I think that's true. The idea of writing something and then somebody saying, "I'm sorry, this will never be seen," is too sad. I love the idea of doing it, but I don't think I'd want to do it unless I knew for a certainty that it would at least be made.

C: So if someone like Steven Soderbergh came to you said, "Here's some money. I've got the money, I want to do this film, would you write something?" Have you ever written on a commission like that?

WS: I never have, really. I don't know if I could. I don't know if I would accept a commission that had a deadline, where I took the money in advance and had to write something. That would be awfully risky. What if I didn't think of anything? I mean, it's not easy to--I don't just toss things off, unfortunately.

C: You spend a lot of your time thinking about these very important, serious ideas and so on, but you must have some guilty pleasures, some stuff that you read or watch that's just fun, that doesn't necessary have any great intentions behind it. So what are some of your guilty pleasures? I'm thinking about trashy TV shows, or junk food, or things along that line.

WS: There was a time a long time ago when I used to say, like a lot of people, "Oh--let's go and see a bad movie." I mean it used to be, maybe I'd go to something like that at that time and laugh and find it fun. I don't know. I wouldn't really do that anymore. Because if I saw a terrible movie I think I would just be depressed by that.

C: You wouldn't be able to enjoy it?

WS: I wouldn't enjoy it, I would feel sort of miserable. But on the other hand there are a lot of things that maybe when I was 20 I would have thought, "Oh, this is just junk," that today, I would have a deep respect for it. I suppose there would have been a time when just the fact that something was a sitcom on television would have made me--I would have acquiesced probably if other people referred to it as junk. I probably wouldn't have thought anything of it if somebody said, "Oh, let's watch some junk on TV," and we watched a sitcom. Well, today if I would see a sitcom that I actually found funny I would probably be very, very impressed. I would certainly not call it junk. I would say, "Wow. That's incredible." For instance, I saw a couple of weeks ago a documentary which had many clips of a show that I saw frequently when I was a child. Yoo-Hoo, Mrs. Goldberg. I suppose that just because it was a sitcom, maybe when I was a college student I would have accepted the idea that because it was a sitcom it must be junk. Today I would be saying, "My God! Those actors are amazing! They're incredible! I'm so admiring of them, what extraordinary performances they're giving." To call it junk, I would be incredibly offended by that and I would say, "My God, who are you to call this junk? How many people have ever been able to do something like that?" So I've changed in that way too I suppose. I wouldn't go to see something if I thought it was junk, but on the other hand there might be plenty of things that I once would have called junk that now I would call fantastic.