J.R. Jones Explores The Many Lives Of Robert Ryan

By Rob Christopher in Arts & Entertainment on May 21, 2015 8:31PM

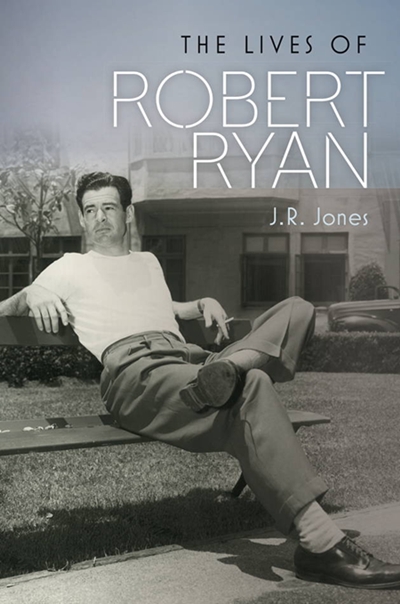

"The Lives of Robert Ryan" is published by Wesleyan.

We've always had a special place in our hearts for Robert Ryan. (Why else would we select Billy Budd as one of the best movies we watched in 2009, and The Iceman Cometh as a film highlight of 2008?) The rare actor who could manage to convincingly go from malevolent to vulnerable in the blink of an eye, he has a magnetic screen presence that completely captivates even decades later.

But it wasn't under relatively recently that we became aware of his Chicago background, thanks to "The Actor's Letter," a Chicago Reader article by J.R. Jones. Now Jones has used that piece as the basis for a book-length examination of Ryan's career and life. On Saturday, May 31 he'll be in attendance at the Music Box for a special screening of Ryan's film noir classic The Set-Up (famous for playing out its story in real time). We recently had the chance to talk with him about the actor's fascinating life, which took him from the edges of the '50s blacklist to John Lennon and Yoko Ono's apartment in New York's Dakota Building.

CHICAGOIST: I'm sure that over the course of your career as a film critic you've seen plenty of Robert Ryan films, but what was the spark that led you to write an entire book about him?

J.R. JONES: At some point before his death in 1973, Ryan typed out a 20-page letter to his children in which he recalled his childhood growing up in Chicago. None of them saw this memoir until after he was gone, and in fall 2009 his daughter, Lisa, passed along a copy to a friend of hers, who in turn passed it along to my Reader colleague Michael Miner for possible publication. For years I had considered Ryan as a possible book subject, so when I heard about this, I asked Mike if I could write a story about Ryan. Published in October, just before the centennial of Ryan’s birth, "The Actor's Letter" turned out so well that I decided to use it as a sample chapter and move forward with a full-length biography.

C: As an adult, he didn't he talk very much his Chicago background. Why not?

JONES: His wife Jessica remembered him telling stories about his father’s friendship with Ed Kelly, who was chief engineer of the Chicago Sanitary District and, later, mayor of Chicago. Seymour Hersh, who worked briefly as a press secretary for presidential candidate Eugene McCarthy, remembers trading Chicago stories with Ryan during the 1968 New Hampshire primary. Growing up, Ryan’s children heard very little about his Chicago years, possibly because of various family traumas that are recounted in the Reader story.

C: He's usually most remembered for his sadistic, villainous parts but in real life he wasn't anything like that. Do you think that dichotomy ever bothered him? Did he ever feel typecast?

JONES: Ryan liked to say that when his agent called with news that Nicholas Ray wanted him for King of Kings (1961), Ryan turned to his wife and said, “Here we go again—Judas.” (In fact he played John the Baptist.) He definitely wrestled with being typecast, partly because less-sophisticated people sometimes made no distinction between him and the racist characters he sometimes played. He once recalled to Harry Belafonte how, shortly after the release of Crossfire (1947), he was walking down Fifth Avenue in NYC and a woman spat on him.

C: He was unapologetically liberal throughout his life. Was he ever threatened by the blacklist?

JONES: Ryan always attributed his luck in evading the blacklist to the fact that he was Irish and a former Marine, a combination J. Edgar Hoover wouldn’t touch. But in fact, shortly before the House Un-American Activities Committee came to Hollywood in 1947, he had undergone an FBI background check in order to travel through the Soviet sector of Berlin and shoot a political thriller called Berlin Express (1948), so he may have been asked about his political associations already, but in a far different context. Howard Hughes, Ryan’s boss at RKO Radio Pictures, was an aerospace executive with connections in Washington, D.C., and may have protected Ryan. In 1950, Ryan agreed to star in Hughes’s pet project I Married a Communist, later released as The Woman on Pier 13. The movie had a reputation around the studio as a political litmus test; people who refused to work on it were shown the door. He regretted doing this movie for the rest of his life and wouldn’t mention it by name.

C: Do you have a favorite role of his?

JONES: His greatest film noir role was undoubtedly the raging cop in On Dangerous Ground (1952), which also included his most haunting love scenes, with Ida Lupino. But he also gave great performances as Mr. Claggart, the sadistic master of arms, in Billy Budd (1962), and as Larry Slade, the hard-drinking former anarchist, in The Iceman Cometh (1973).

C: What do you think is his most underrated film?

JONES: That’s hard to say, because he made so many good films that are unknown to most people: Act of Violence (1948), Caught (1949), About Mrs. Leslie (1954), Men in War (1957), God’s Little Acre (1958). He was very proud of his performance in Inferno (1953), directed by Roy Ward Baker, as a millionaire stranded in the desert by his cheating wife and fighting to survive. That movie was part of the first wave of 3-D features and for years was impossible to see, though it was shown in New York a few years ago and was recently issued on Blu-Ray.

Ryan gave a tremendous performance in a live TV adaptation of The Snows of Kilimajaro in 1960, as the writer dying of gangrene in the jungle while his life flashes before his eyes. The production is a story in itself; the present-tense narrative and flashbacks were supposed to be taped and edited for broadcast. About a week before the air date, however, director John Frankenheimer learned that for legal reasons he would have to stage the play live, which required all manner of last-minute improvisations. At the center of all this, Ryan was giving his first live television performance, and he’s excellent. Broadcast on CBS, the play has never been issued to home video; you can see it only at the New York and Los Angeles facilities of the Paley Center for Media.

C: I've read his apartment in the Dakota Building in New York was subsequently taken by John Lennon and Yoko Ono. True story?

JONES: Yes. Ryan’s children were grown and living on their own when his wife died of cancer in 1972, so he decided to move into a smaller place and he sublet his unit to Lennon and Ono. His daughter Lisa remembers tagging along to meet them and being startled that Lennon was a fan of her father’s work, particularly his westerns. The two men chatted about their roots in Ireland, and the deal went through; the Lennons moved in early the next year and eventually bought the unit.