CSO Kicks Off Mahler Month

By Alexander Hough in Arts & Entertainment on Nov 30, 2011 5:30PM

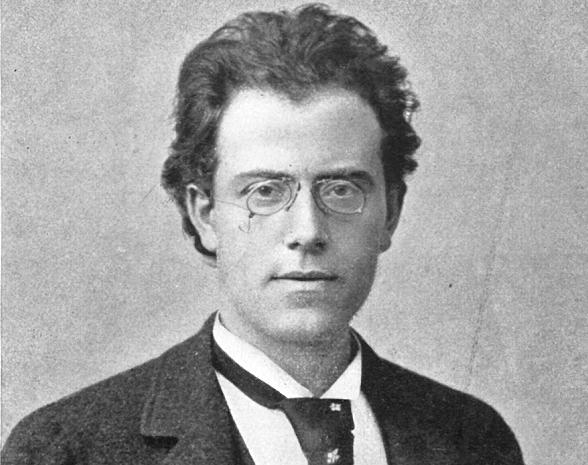

Considering the popularity of the music of Gustav Mahler (1860-1911) - Mahler symphonies are to orchestra seasons what the Isley Brothers’ “Shout” is to wedding receptions - the Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s commemoration of the 100th anniversary of Mahler’s death has been reserved.

So far, the CSO has performed only his Fourth and Ninth Symphonies (the Seventh was scheduled for last March but was moved up in the reshuffling following music director Ricardo Muti’s extreme gastric distress), as well as the entire program from the last concert Mahler conducted. Even then, the CSO incorporated Mahler in this current season with their tribute to the music of 1911-1912. Still, the CSO isn’t letting 2011 end without a nod to the great late-Romantic composer, dubbing December “Mahler Month” and filling it with three programs featuring his music.

Mahler’s popularity is warranted. His music is the culmination of Romanticism: dramatic, often with over-the-top emotion; spread across as wide a dynamic range as an acoustic ensemble is capable of; scored for enormous orchestras; and filled with hummable, even catchy tunes varying from sweet melodies to violence that is dissonant but always (at least until his final symphony) tonal. After Mahler, traditional classical music could go no further; it’s not a coincidence that, following his death, composers went in a multitude of directions, with the predominant one, led by Arnold Schoenberg, advocating the destruction of tonality. Mahler is the high-water mark of the European classical tradition.

We love Mahler, and not because of his historical place: his music is exciting. It’s full of extremes - anger and despair one minute, all gooey sap the next. And it’s all beautiful enough that we drop our jaded, cynical act for a little while. Not all of us feel this way, however, including Muti, who recently voiced his too-polite-by-half displeasure:

“With the symphonies, I have some problems. Sometimes for ten minutes of paradise, you have twenty minutes of—well, something else, I don’t know what.”

We’ll agree to disagree and be thankful that, for these concerts, Muti has handed the baton to a trio of brilliant conductors: Jaap van Zweden, Michael Tilson Thomas, and Esa-Pekka Salonen (who was supposed to conduct the aforementioned Mahler 7 prior to rescheduling).

Van Zweden gets first crack, conducting this weekend’s series of concerts (Dec. 1 - 3) featuring Mahler’s First Symphony. It is his most accessible symphony, and not just because it’s one of just two that clock in under an hour, although that helps. The work is more moderate, in general, and is structured in traditional symphonic form, though it still gives a sampler pack of Mahler’s musical tendencies. The slow opening is typical of symphonies, and Mahler’s is always compared to the beginning of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, with its drone on the dominant (in both, A in the key of D) giving way to major thematic elements, but we think of the passage more as one of the timeless, ethereal worlds Mahler loved creating, evoking nature explicitly (the clarinet bird calls) and subtly (the distant trumpet calls intimating an expansive world). In the first movement, as in so much Mahler, darkness and light intermingle, although the latter predominates, continuing into the bouncing second movement, a ländler (a lively dance in 3/4, for those of you who haven’t been to da Austrian club recently).

Things get a little weird in the third movement, a funeral march with a minor key version of “Frère Jacques” (the introductory theme will be played by the CSO’s entire bass section, as they did on their 2009 recording, rather than by a soloist as is usually - and mistakenly - done). Throughout, Mahler alludes to low-brow music like military bands and Jewish folk music from his upbringing in what is now the Czech Republic, and leads directly into a tumultuous minor-key finale. The happy resolution over adversity is nothing new, and compared to his later works, the journey to triumph feels less fraught, but seeing a bunch of French horn players stand up at the end because Mahler wanted it fucking loud, well, that’s pretty awesome.

There is, of course, a first half to the concerts, too. The show will open with the CSO’s first performances of contemporary composer Steven Stucky’s Rhapsodies for Orchestra, and that will be followed by Mozart’s Concerto for Bassoon, an instrument ex-bassoonist and current actor Rainn Wilson described as sounding like an anemic fart. That description is both too generous and unfair: In the wrong hands, a bassoon can sound like a powerful fart authored by, say, someone experiencing extreme gastric distress. In the right hands, though - such as the supremely talented CSO principal David McGill, who will be this weekend’s soloist - it can be silky, expressive, and almost entirely unlike a fart.

Listed below are the other upcoming Mahler Month concerts. All are highly recommended.

Dec. 8 - 10

Michael Tilson Thomas, conductor

Jeremy Denk, piano

Mahler - Blumine (originally a movement of Mahler 1)

Beethoven - Piano Concerto No. 3

Brahms, orch. Schoenberg - Piano Quartet No. 1

Dec. 15 - 17

Esa-Pekka Salonen, conductor

James Matheson - Violin Concerto (CSO co-commission, world premiere)

Mahler - Symphony No. 6

Mahler 1 will be performed Thursday, Friday, and Saturday, at 8 p.m., Symphony Center, 220 S. Michigan, $29-$165, $10 student tickets available for Thursday and Friday